The first time I tried to die, I was in a classroom in East Pyne. If you’ve never died in East Pyne, it’s hard to describe how wonderfully the location situates itself for death. The dark wood, the low hanging lights. It was November, when everything outside conveniently dies as well. Method acting can only go so far.

The light in the classroom slanted itself against the stained glass windows as I mimicked taking a draught of something dire—I didn’t have time to retrieve a proper chalice— and allowed the poison to work itself through my veins.

I held my throat and closed my eyes, imagined my skin growing pale as whatever substance in the chalice revealed its capacity to mime the stopping of my heart.

Deadly nightshade, or atropa belladonna, tastes sweet on the tongue. It causes hallucinations and convulsions, though women used it for its cosmetic purposes— paint some across the eye, and it dilates your pupils enough for you to look seductive by Edwardian standards. I’d done my research. After a few shuddering breaths, I collapsed on the ground, sprawled out in a position that could have been mistaken for sleep.

At this point in Shakespeare’s play, this poison was only supposed to reduce me to a stupor, a feigning death. Juliet wants passion, not a loveless marriage, so she agrees to fake her own death in order to steal away with her paramour. I believe I don’t need to explain the ending. This was our first rehearsal of the death / sleep scene. I had been nervous of my death all week—I had nervous laughter issues that I hadn’t told anyone in the cast about.

In this death, I tried to focus on my breathing, which is an odd thing to say about death. I couldn’t fall asleep because I might have missed my cue. I had never felt the presence of my body so intensely. The director called “scene,” and I crawled to my feet.

***

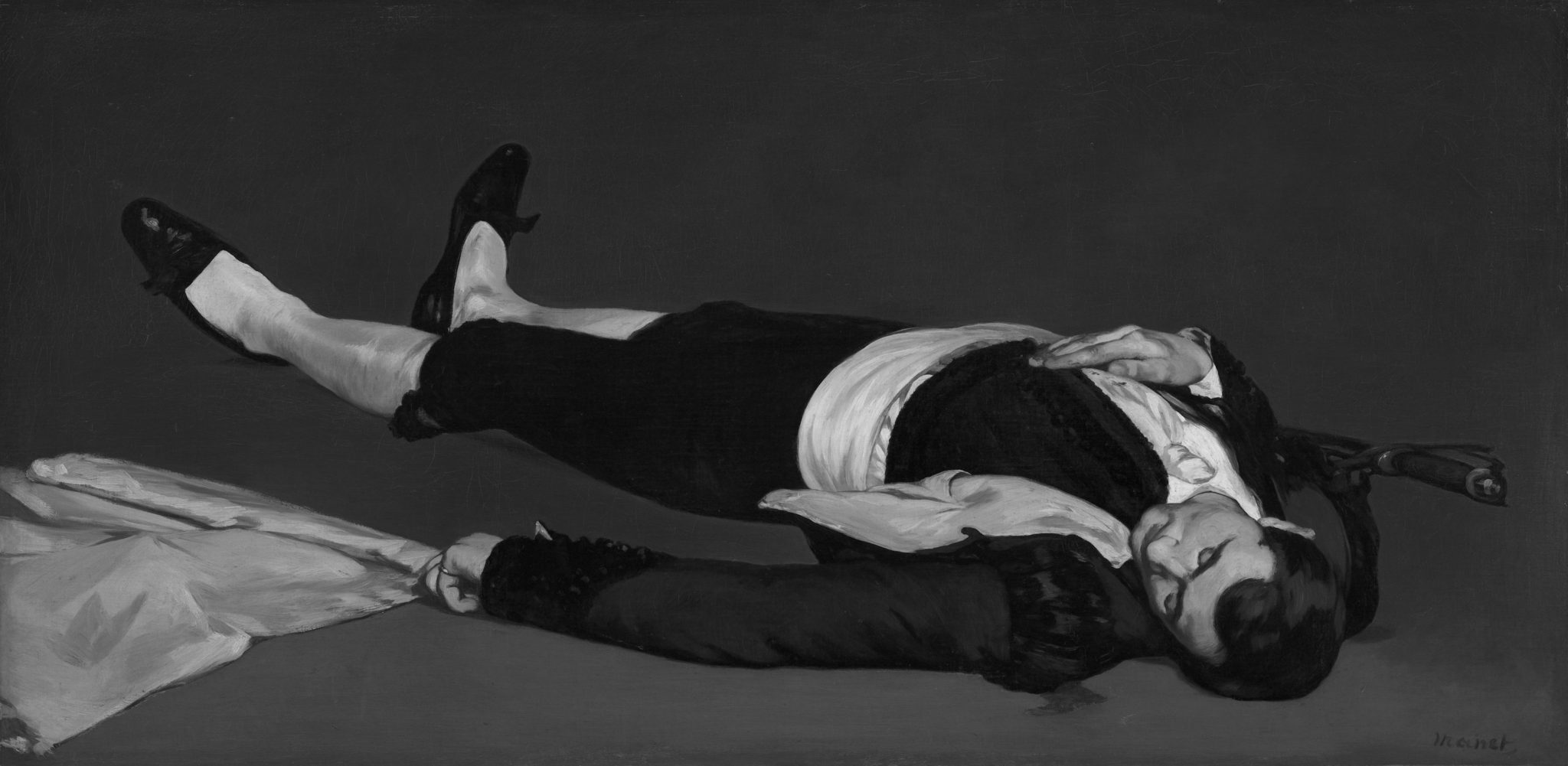

Theatre has always been close to death. It allows actors to perform death in a way that they are not afforded in life. Literature allows us a similar freedom, but not quite the same. In literature, we can die again and again and emerge from the book unscathed. In a play, we have to either participate in this death, or, silent in our seats, we watch as death takes place. I paraphrase Aristotle’s Poetics here when I say that death in the context of a tragedy allows the audience member to feel catharsis. The audience member can watch a character die and be reminded of her own mortality, so long as the plot contained the right concoction of pity and fear.

Dying onstage is a strange mixture of the two. Says Freud, in his essay Our Attitudes Towards Death: “Life is impoverished, it loses in interest, when the highest stake in the game of living, life itself, may not be risked.” We avoid death, so we don’t allow ourselves to think about it. We don’t mention it in conversations out of courtesy, and thanks to modern medicine, we believe ourselves impervious to it, or at the very least, able to ward death off with enough antibiotics and good planning. In this way, we remove death from life. If it’s far away, it can’t hurt us. Dying onstage is strange, because when you are the one doing the dying, you are most aware that it is a farce.

I died twice a week for two weekends in November of 2014, thanks to Princeton Shakespeare Company’s production of Romeo and Juliet. I always came back to life, though.

After every death, I got in the habit of monitoring my own breathing. There is an uncanny number of actors who have actually died onstage, some in the process of their own stage-deaths. The Wikipedia page offers a macabre litany of vignettes. In 1673, Moliere died in a coughing fit while acting in a play entitled “The Hypochondriac.” In 1960, Leonard Warren died before he could perform his next aria. The piece was entitled: “to die, a tremendous thing.” Many stage deaths that surpass the stage are the result of improperly loaded guns, bullets mistaken for blanks. More confusingly, many actors have died at the same moment as their supposed stage-deaths; the audience left reeling at the uncanny performance, only to suspect, when the actor took too long to rise…

Kneeling on the stage floor, I always checked the handle of my stage-dagger with my fingertip before plunging it into my own side. “Believe in your own death,” said the acting coach hired to work with the Romeo and Juliet cast. He demonstrated in front of me. “Your death is by asphyxiation. So try to make yourself hyperventilate. Breathe in and out, in and out then close your eyes like a dimmer switch, and slowly… slowly…” he pitched forward, and for close to four minutes he exhaled loudly. I didn’t know what to do, so I just watched and clapped when he was done.

I had never acted before, and so I embraced all suggestions of method acting to help me find character interiority I didn’t know how to find. Someone suggested I learn how to cry on command, though since it was a challenging thing for most actors, she said, I might not be able to do it. I was competitive, and spent hours staring at my desk lamp with my eyelids held open.

More than that, I tried to hold death close to my person. Shakespeare’s sonnets made sense, and so did Donne—these poets lived during times of plague and death. Death was all around, everyone was doing it! So stupid to waste hours without sex and lovestruck verse when the person you loved might very well die before you could tell them you did.

I was acting in this play around the same time I was spending most days thinking about kissing someone I knew. As often as I fantasized about us finding our way near each other on campus, on the same garden path, on the same wavelength, I fantasized about him sitting in the audience of the play. It wasn’t that I wanted him to see me act, or anything like that (I know my strengths better now and acting is really not one of them). But still I looked out into the audience each night, knife strapped behind my back.

It’s common to imagine our own deaths. The difference for me was that I saw who would come to watch. I wasn’t sure if I wanted him to see me act or if I wanted him to see me rise from death.

***

The first time I died onstage, I tried to inhale believably from my vial. The prop had been in the costume room for quite a while, so when I inhaled it, I inhaled months worth of old dust. This was very stupid. I tried the hyperventilation technique, but it only made me want to cough more. I couldn’t cough the dust out, because, death. I lay down on my pallet and tried to extinguish the match struck in my lungs, while feigning a deathlike sleep.

I had to lie there for two full scenes while various cast-mates mourned over my dead body. I tried to cough silently behind my stage mother’s obscuring arms. Coughing silently is not easy to do, especially so onstage when there is a large light trained on your sleeping form. My eyes burned with the pressure of keeping the cough inside, the stubborn workings of my own lungs.

I waited out the entire scene before running off into the wings. My own body was stupid enough to physically resist dying, I thought as I coughed and retched offstage. Dying is an art, wrote Sylvia Plath in her poem Lady Lazarus. I had managed to Lazarus myself, and found in the process that I didn’t do it very well. Dying is an art for those who are willing to practice it. Dying is difficult for those who hang stubbornly to a survival instinct. The white light isn’t a light, it’s a cough.

After the show ended that night I hurried out of Theatre Intime, excused myself out of the crowd. The wind was cold on my skin and I couldn’t stop walking around. I had never felt more able to inhabit my own body, the knowledge of my heart, working and working and working.

The show was longer than two hours despite significant script cuts, so by the time I checked my watch again it was well after midnight. I walked myself to the football field and counted how many hours I had left until I had to die again.

Leave a Reply