Every suburb is defined by its city. At least, that’s what my southern California suburban experience was defined by, the glowing metropolis over the hills, alluring and enigmatic as Faye Dunaway in “Chinatown.” Los Angeles tells the story of itself through movies, the city’s own artistic lovechild, and the best ones usually take an interest in the land itself, as with the seedy and corrupt property dealings in Polanski’s film.

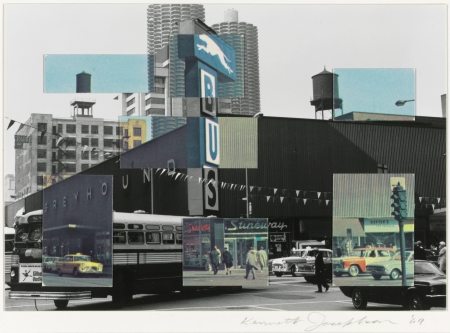

But movies may not be the best medium for the complex and gritty details of city life—gentrification and ghettoization don’t make for good plots, let alone good blockbusters. They do, however, make for some great pictures, as evidenced by “The City Lost and Found,” a current exhibit in the university art museum featuring photos of major U.S. cities from the ‘60s to the ‘80s.

The exhibit tries to capture what urban life felt like in different parts of the country during that strange, transformative period, when America became more recognizably what it is today; we’ve gotten more cynical since the ‘60s, we’ve seen more Vietnam reruns (endless wars, countless deaths) since the ‘70s, and we’ve improved our collective fashion sense since the ‘80s. To this end, the photos on display don’t only capture the large-scale changes in technology and urban design, but also the fleeting, intimate glimpses of people’s lives, as if we were a passer-by on the sidewalk.

These shots add up to something of a collage, a mixture of different styles, subjects, and themes, greater than the sum of its parts—in many ways, not unlike a city itself. The exhibit showcases not only the differing narratives of different cities, but also the opposing narratives—of progress and decay, wealth and poverty, community and isolation—within individual cities. The exhibit doesn’t really champion any of these narratives specifically, suggesting that no one story can fully capture a city’s style or meaning. That’s cool, and probably true, although it did leave me wanting a little more of an argument from the exhibit, a sense that things have progressed (or regressed, or whatever else) in some way.

That may be why I was much more interested in the photos taken at street-level than in the vast, sprawling cityscapes. In Danny Lyon’s series “The Destruction of Lower Manhattan,” for example, there’s a picture of New York from far away, where it looks like a gleaming, pristine metropolis. From that vantage point, it also looks pretty much the same as it does today, which is why it didn’t interest me much. When the camera descends to the streets, however, we see the city in all its grimy realism, with its boarded-up buildings and downtrodden residents. And Lyon is especially interested in the dirt and destruction on display at street-level, making the trite point that city’s aren’t nearly as perfect in reality as they are in the collective imagination.

The exhibit does feature some street-level photos that go beyond this simple argument, however, to get a sense of New York’s life, its personality, the way one feels to inhabit its space. Arthur Tress captures this ethos in one of his photos of graffiti, in which some unknown artist has spray painted “the city must find its meaning in its people.” Aside from making me yearn for an era when walls might be coated by urban artwork and catchy slogans instead of photoshopped bodies pushing unnecessary products, Tress’ photo gets at the heart of the exhibit—cities may be made for people, but they’re also made of people. Though a city only consists of its various buildings and structures, it’s worthless and hollow without its residents.

Tress’ photographs capture the increasing importance of the individual in the confines of the city. In one photo, a weathered sign affixed to a chain link fence in Astoria reads “This is not a public playground.” But the people featured in many of his other photos seem to take that statement less as a law than as a challenge, appropriating piers, junkyards, and other places filled with the city’s detritus for their own personal enjoyment. There’s an endless competition between the city, which makes the rules, and its residents, who break them. These photos capture casual, quiet moments, such as one of a woman sunbathing serenely on a rundown dock, and speak to the sort of creative, improvisational rule breaking that cities encourage, intentionally or not.

If cities are restrictive, it’s only in the same sense poems are restrictive, taking advantage of certain constraints in order to produce something new and beautiful, like how pressure turns coal to diamond. Cities build themselves up from scratch, adding grids and buildings—but within these uniform boxes, people find endlessly creative ways to express themselves. Romare Bearden’s collage “The Block II,” for example, features a vague and minimalist backdrop of brick walled apartment buildings, with row after row of windows, through which we can see all the variety and intricacy of life in New York: a mother nursing, two women undressing, a forlorn child sitting on his building’s front steps. The windows in Bearden’s collage become miniature canvases, the dimensions of which the residents exceed, spilling out onto the walls and streets around them, inhabiting their city’s ether, and in a sense, becoming part of the fabric of the city itself.

A lot of the photos in the exhibit seem uncertain whether the people make the city, or the city its people. Vito Acconci’s performance artwork “Following Piece,” for example, has the artist choose one person at random on the street, and trail him until he reaches his destination, usually a private space like a home or an office. (On display in the museum are the instructions Acconci used, as well as a shot of him walking.) The piece suggests that the city’s layout is a map of possibilities, connecting everyone in brief moments of intersection. Or, more cynically, it points out that, though there are more buildings in New York than anyone could ever hope to visit, most people simply go from home to work and back again, that the most unique thing about our lives may be the addresses at which they unfold.

There’s a definite sense that the growth of American cynicism kept pace with the growth of American cities from the ‘60s to the ‘80s. The simple, idealized multiculturalism and unity present in the earlier exhibition photos are absent in the later ones, replaced by prejudice and isolation. Martha Rosler’s “Downtown” series features the usual scenes of daily urban life (children playing in the street, abandoned buildings, etc.), but make a point of maintaining their distance from their subjects. There’s always something in the way (a passing bicyclist, or a car’s dashboard) to remind us that we are fundamentally separate from other humans—even our own neighbors. In one of Rosler’s photos, an older white couple sits on their stoop, ignoring and ignored by the younger Hispanic couple sitting right next to them. Despite some similarities between the couples (both women have their heads tilted to the right, and both men are covering their faces, meaning no one is looking at anyone else), they seem utterly uninterested in the other’s presence.

All these photographs—Tress’ scenes of urban rulebreaking, Bearden’s beautifully eclectic collages, Rosler’s moments of voyeurism—present a possible narrative of the changing role that cities have played in forming their inhabitants. If cities once united people with a collective identity, they’ve since become merely places where a bunch of individuals live in close proximity. This trend continues even today, as generic chains and brands increasingly replace the small, unique stores and businesses that give a city its distinctive flavor, making every city resemble every other city.

These were also the photographs of New York that most captivated me, and I think it’s because they take such an interest in the individual lives there. I’ve lived in suburbs all my life (the first ten years spent outside Los Angeles, and the next ten outside New York), which made me more fascinated with cities than I would have been had I actually lived in one. Wasting my teenage years in dreary Connecticut, I resented my parents for, as I saw it, depriving me of a potentially awesome adolescence in a city. I often visualized what my urban alter-ego might be doing—taking the subway instead of learning to drive, going to clubs instead of parties in my friend’s basements, wearing cooler clothes, visiting more art museums.

But of course, this was a fantasy based mostly on approximations and stereotypes, which is to say, on nothing at all. I didn’t really know what it felt like to live in a city because I had never lived in a city. That’s probably why I was drawn to the photos of people—they give a visceral sense of what life might look like in a certain city at a certain time.

The L.A. photos specifically brought back memories I didn’t know I had. I haven’t visited L.A. in several years (compensating instead by taking frequent trips to New York). I suppose I had grown used to how compressed New York’s tall buildings and obstructed sky make me feel—that is, until I saw the photos of L.A., and remembered what it felt like to be able to look up and see the expansive sky in all its smoggy, stained beauty. In these photos, the sky has a presence, foreboding and dark, that may reflect the general unease infecting L.A. in the early ‘60s.

This tension eventually exploded into the Watts Riots, photos of which are featured prominently in the exhibit. Incited by police brutality against a black man, the riots prove that though cities have their narratives of progress, some things never change. The riots consumed the city (and national attention) for a whole week, as residents expressed their pent up rage and discontent by destroying buildings, setting fires, and killing 34 people. More importantly, it transformed Los Angeles, which was forever after branded with the image of its buildings in flames (memoraliazed in Ed Ruscha’s aptly titled “Los Angeles County Museum on Fire”). This is where the “city lost” part of the title comes in—those tumultuous few years in the late ‘60s when American idealism died with Kennedy, King, and large swaths of L.A.

But there’s also the “city found” part of the title, a suggestion that, sometime between the ‘60s and the ‘80s, something lost was reclaimed. What that is, exactly, is hard to say, given the ample scenes of destruction and isolation on display. It’s even harder to say when one considers that many of the problems the exhibit highlights—wealth inequality, segregated neighborhoods, police brutality, decaying infrastructure—persist today.

Despite this, there are some signs of optimism in the exhibit. In 1972, seven years after the Watts Riots, the architectural critic Reyner Banham shot the documentary “Reyner Banham Loves Los Angeles.” The film features Banham travelling along the city’s freeways, his analytic narration of L.A.’s architecture interspersed with sassy commentary from the car’s GPS. The car becomes a sort of companion to Banham, which is fitting—nobody in New York has a car, but in L.A., you’re a nobody if you don’t. Banham is fascinated with this modern “autopia,” going so far as to call the billboards along the freeway an outdoor art gallery. His film points to what cities may have found or reclaimed: the dizzying sense of novelty and of modernism, the feeling that big things are happening, and more importantly, in your own zip code. Banham’s fascination with cars, freeways, and ads may seem quaint now, but their unique combination and presentation was exactly what made L.A. so special to him. And part of that persists today—L.A. just can’t shake the romanticism of the car and the open road, climate change be damned.

But that’s specific to L.A., and part of what makes “The City Lost and Found” so special is that it doesn’t just concern itself with individual cities, but with all American cities, with urban life. John Humble’s “300 Block of Broadway,” chronologically one of the last photos of the exhibition, features the towering skyscrapers of L.A. in the background, their tops cut off by the top of the frame, as if they were filler. The city depicted could almost be any city—it certainly makes no difference to the people in the foreground, going about their business next to some brightly colored storefronts. One shops for a pair of Levi’s, a few wait to cross the street, and some walk along, as unconcerned with the metropolis nearby as they are with the others on the street. But even if Humble’s picture isn’t the vision of urban unity on display from the ‘60s, it’s still optimistic. One of the stores sells Mexican food, pizza, Chinese food, and burgers—an ethnic cornucopia as diverse as the passers-by on the street, utterly disinterested with each other, but still swerving to make way for one another, still part of something greater.

Leave a Reply