Homecoming

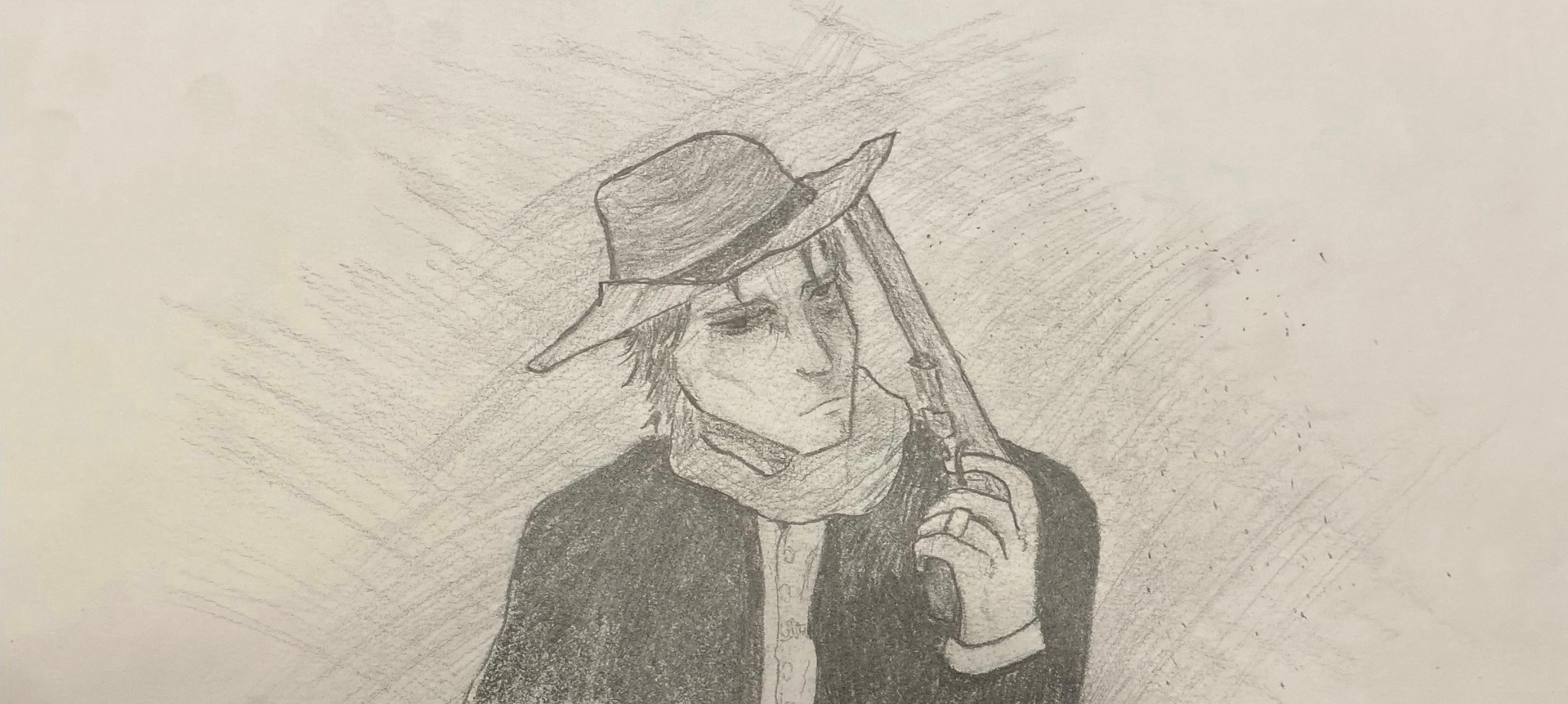

The Old Desperado missed his wife. He had seen all there was to see. He had dueled pirates in Jamaica over buried gold, robbed the legendary Zorro of his sword, and stuck up freight trains with Italian banditos in Colorado. He had fought with Santa Anna at the Alamo and rode off with Davy Crockett’s coonskin cap. He had fought on every side of the three Civil Wars and lost every time.

The Old Desperado was tired. He missed California. He missed the bungalow with the lava stone fireplace he had built with his brother, back when their hands were rough from chopping wood and their dreams stretched farther than the hills. He missed the grain of the spruce patio under his feet as he drank coffee at sunrise. He missed the avocado trees his wife had planted the summer before he left home to see the world. He missed the smell of the ocean. And he had finally decided he was far too old to be spending his nights with a rock for a pillow and his aging gray horse, El Camino, for conversation. So the Old Desperado threw his saddle over the horse’s back and, with a swift kick and a loud whoop, rode home, leaving nothing but a cloud of dust and a neatly stacked pile of rocks.

Los Angeles was exactly as he remembered it. The cantina where he had met his wife still had the same dusty red-gated door. The air still carried that sweet-salty-sea-smell that bewitched tourists and bothered horses. The Old Desperado was not from here – nobody was – but in his heart, the city of angels had long replaced the quiet old San Pedro of his youth. And there was one reason for that. Forget the sea and red-gated doors; Los Angeles was home because of the Old Lady.

She sat at their old corner table, just to the left of the red doors, sipping rum and drowning big round onions in ketchup. Across from her, in his old familiar spot, was a small plate of fried plantains and rice.

“Eh la bas, ma petite amie,” he called to her, just as he had since he was a little boy reading treasure maps of the French Quarter by candlelight.

“Yo, Buddy. Been a while, baby.”

She was older than he remembered, the grooves in her face deeper, her hair thinner. She was the most beautiful woman the Old Desperado had ever seen. Time had softened her edges but sharpened her

presence – she sat straight-backed, her eyes still bright, still sharp. She had built a world in his absence, had ruled it with quiet authority, tending their home, their trees, their ghosts.

“Missed me?”

“Not at all.”

And so the Old Desperado and the Old Lady walked home, cutting through the garden footpath, clearing away the overgrown banana leaves and dropping avocados.

A Ghost Story

The Old Desperado spent the next month picking up and catching onto rhythms, new and old. Some were easier than others. He retired his riding boots for sandals. Clearing the garden was simple with another pair of hands. Going to the saloon each night, singing along with the old men and ghosts, was easier still. But he never got used to how soft the bed was. He tried forty-two different positions, threw away the pillows, stuffed his ears with candle wax. None of it worked. And so each night, the Old Desperado crept out of the Old Lady’s room, saddled El Camino, and rode the hill’s dirt roads until the sun rose.

When the Old Lady discovered him sneaking out one night, she was enraged.

“How dare you, Buddy? Am I not enough?”

“It’s not that, ma petite amie. I am restless. My feet miss the feel of spurred boots.” “Why?”

The Old Desperado said nothing, and the Old Lady stormed out. She had built her own peace in his absence, yet now he threatened to disrupt it, unsettled, unfinished. She was done waiting on a man who could not stay.

He slipped his sandals back on and walked down to the saloon’s red-gated doors to listen to the old men and ghosts.

The first ghost he spoke to was his father. He had killed his father when he first left quiet old San Pedro all those years ago.

“How long are you back for this time, mijo?”

“Forever, Papi.”

“I don’t believe you.”

“It’s true. I’m tired of the road. I missed home. I missed my wife.”

“Well, which one is it?”

“What do you mean?”

“How can you miss home and be tired of the road? That is your home, mijo.”

“My wife is my home, Papi.”

“But it is El Camino that you go to every night.”

The Old Desperado stared into his father’s dull round eyes. A small splash of green sat in their center. He had never noticed that in quiet old San Pedro. He finished his too-small bowl of rice and plantains.

“Goodbye, Papi.”

“Where are you going, mijo?”

“I need to go tell a story to a ghost.”

Eh La Bas Ma Petite Amie

Eh la bas ma petite amie,

I hope you know I love you more than you could ever know. And I am so sorry. I returned to you just like I said I would, but somewhere on the road I must have lost you. At some point the tired nights became my home. I belong in dusty boots. Our bed is too soft.

In my life I have had three homes. Quiet old San Pedro was the first. I left it to find space to breathe, but I left too young to know that some places breathe back. And in that space I found my second

home. You are by far the most beautiful home I’ve ever had. I never should have left you in the first place. I wanted to find myself and I don’t know if I did. But I found another home. I was alive. I returned to you tired and sore and a new man. I felt that I owed you my return. But I am not the man I was when I left, and you are not the same woman. I am an Old Desperado. I belong to long nights and bruised bones. And you are an Old Lady ruling in a court of soft beds and overgrown gardens. The people we were when I left don’t exist anymore. I’ve spent too much time as a stranger in a strange place, and we are strangers again.

When you read this letter, you may call me a coward. A no-good bum who rode away from his family in the night rather than talking to them. You are right. But I cannot bear to live in this ghost town any longer. I can’t eat too-small plates of rice and plantains. I can’t live with the ghost of you and remain alive. I’ve spent the last 30 years being born. I don’t intend to spend the next 30 dying. See you when I see you,

Buddy

The Old Desperado placed the letter on the Old Lady’s nightstand and kicked off his sandals. He put his boots back on and saddled El Camino. With a sharp kick, he started up the hills. He only looked back once. When he did, he saw the Old Lady and a flickering light walking the garden footpath, weaving through the avocado trees.

Pulling the reins, he turned back east. Leaning low against the horse, he trained his eyes on the road and rode off into the sunrise.

Leave a Reply