I entered Alexander Hall, heart pounding, clutching a small spiral notebook and an orange ticket. The narrow, rounded hallway bordering the theater was filled with a labyrinth of lines. I frantically weaved through and approached an usher to ask her where I could wait in order to sit in orchestra seats. She took a look at my orange ticket, smiled, and said, “I’m sorry, that’s not a choice you can make. Only blue-ticket holders can sit on the first floor. You have to sit on the balcony with the students.” I told her that I was a due-paying member of Friends of the Library, and should be allowed to sit downstairs with the “grown-ups.” She forced another smile as she looked me in the eyes and said, “Don’t worry, we know that the students are sitting up there and will be sure to call on you for questions.” As I realized that I had no choice in the matter, I resigned to sit on the balcony.

My aggressive enthusiasm for this event stems from my near obsession with Woody Allen since childhood. This fixation started at the age of 11—we had a VHS of Take the Money and Run in our home, a mockumentary about an inept bank robber. I watched again and again, making me perhaps the only prepubescent who could recite a pre-1970 comedy line-for-line. My personal fascination with his films gave me the false impression that Woody’s one-liners were part of the middle-school vernacular. However, most of my peers didn’t know what to make of it when I would squeak lines like “I think people should mate for life, like pigeons or Catholics.”

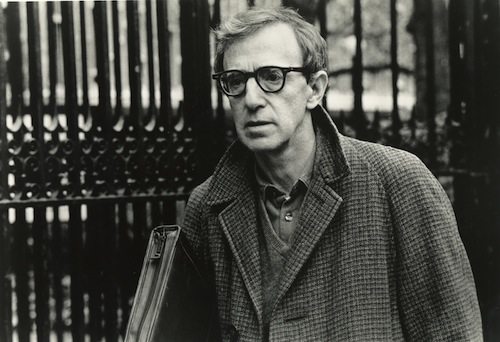

Woody Allen is a myopic, Jewish redhead who lives in the Upper East Side of Manhattan—so on paper, we are the same person. And although he lived just four blocks from me during my school years, I am the only member of my family who hasn’t crossed paths with him.* When I saw his name in black print on the front page of the Daily Princetonian: “Woody Allen to speak on campus Oct. 27,” I knew that my time had come. He was coming to campus for a session hosted by Friends of the Princeton University Library. I began to scrape every possible resource I had in order to obtain a ticket. I paid for a membership of this group, and went to Frist four hours before sales to wait in line for tickets (though I was the only one in the line for the first three and a half hours).

To prepare for the event, I listened to hours of recorded interviews from the TV and radio, so that I could curate a selection of questions that Woody had never been asked before. Unless I somehow ran into him at the checkout line at our local supermarket, this would likely be the only opportunity I would ever have to ask him a question. One of the questions I wanted to ask was about the synthesis of humor, and how he worked it into his screenplays. In his essays and plays, there are lines (or sometimes even references to entire storylines) that were later incorporated into his screenplays. Annie Hall, for example, is really an amalgam of one-liners from his short stories and essays. Did he first establish a preconceived narrative arc or did he just lay out the jokes ahead of time and link them together?

After investigating previous interviews, including a 400-page in-depth interview by Stig Bjorkman, I realized that it would be nearly impossible to ask Woody a new question. I noticed that he would often give responses that were not at all extemporaneous. He would freely borrow jokes from himself, and give preformed entertaining answers that didn’t say anything truly intimate. After sifting through these questions, I decided that my priority was to ask him the most obvious question: why had he decided to donate his works to a gated community in New Jersey, perhaps the only place that his film characters never bothered to go? Of all places, why would Woody give his papers to Princeton?

I sat on the edge of my balcony seat, rehearsing the question in my head. Between Woody’s answers, I shot my hand up, hoping to be called on. The next hour was an emotional rollercoaster—

Euphoria/nausea: Seeing Woody in the flesh for the first time.

Outrage: Hearing Library patrons ask zinging questions like “So, what is a typewriter?” and “Are you thinking about doing any TV shows?” and the last “question,” “I just want to say, thank you so much for all of your movies.”

Anxiety/nausea: Enthusiastically shooting my hand up to ask my question.

Despondence: Walking out of the theater, questions unanswered.

Since the event, I have searched for the answer to this question—why Princeton? The answer lies in Woody’s relationship with Laurence Rockefeller, the origin of which “remains unknown,” according to the Princeton Alumni Weekly. Since I now had no way to ask Woody about this, my only option was to investigate the relationship from Laurence’s end. I got in touch with former members of the Board of Trustees who were on the board while Laurence was, and begged them for an explanation. According to them, Laurence had an infatuation with Woody Allen’s work; he shared this with then-University President William Bowen.

Laurence pushed for the board to recognize Woody’s films by presenting him with perhaps the pinnacle of human accomplishment: a Princeton University Degree. In order to offer Allen the honorary doctorate, Laurence faced a challenge similar to my current one: how would he get in contact with Woody? He conspired with young trustee board members to figure out how he could “cross paths” with Woody. After researching (read “stalking”), the young trustees found that Woody played clarinet weekly at Michael’s Pub in midtown Manhattan. It was proposed that the young trustees approach him after a performance and offer him the honorary degree. But before that ever happened, Woody responded to the proposal in a manner consistent with his famously cited Groucho Marx line: “I would never join a club that would have me as a member.” He refused the degree. However, he developed a fast friendship with Laurence. Reportedly, Woody even cast Laurence as an extra in some of his movies, and Laurence provided locales for filming. This is where the story of my trustee board accomplices comes to an end. Beyond this, we do not know how their friendship further developed, or why Woody ended up leaving his papers at Laurence’s alma mater. Woody’s side of the story is yet to be known.

And so as an open letter to Woody, I will send this article torn from the pages of the Nassau Weekly. Maybe I will wait outside the Carlyle Hotel (his current clarinet-playing locale), or just spend an absurd amount of time pacing the mile-wide radius that defines our shared zip code. Woody, I apologize for the boring questions you received that day in Alexander Hall. Hopefully some day I will bump into you, with your rain hat pulled over your face, and inappropriately beam and wave at you. And maybe, if we happen to be waiting at a red light together, I can turn to you and ask: “What was it really like between you and Laurence?” *

*On November 27, 3:30 pm (exactly one month after the Q&A session), Lily Offit ran into Woody Allen on Park Avenue. Both were wearing beige rain hats. She wanted to ask him The Question but decided against it, on the basis that this would make her the most obnoxious person ever.

Leave a Reply