Light shines upon one generation and casts its shadow over the next. As art is itself a shadow of life, families of painters offer a rare glimpse of childhood and child-rearing as they happen off the canvas in real lives. N.C., Andrew, and Jamie Wyeth––father, son, and grandson––shaped not only the course of American art but also the course of each other’s lives. The Wyeths all grew up along quiet, scenic coastlines, where they received conventional training in oil painting. With all these constants––not to mention genetics––the nuances of fatherhood are left plainly visible in the differences between the artists they grew to be.

[Disclaimer: Publicly available information on the Wyeths is sorely lacking. But in studying this family as a family of painters and paintings, and in studying said paintings as works that change and move––changing each other as they are themselves changed––the Wyeth family tree might be cast in a new, more illuminated color palette.]

The Wyeth saga began with N.C.: a maverick unimpressed by his industrializing world who became infatuated instead with adventure, romance, and old America––back when the connection between humanity and nature was more immediate. Unlike his heirs-to-be, N.C. never developed any kind of a stylistic focus, instead constantly challenging his materials to reach for new highs, new kinds of dynamism and sublime intensity. For the bulk of his career, N.C. waged war upon his canvases, disposing of realism whenever it served to heighten [insert literally any emotion here]. He wanted to catch his viewers off guard, challenging their urban malaise with blasts of good ol’ rustic drama. N.C. was a walking anachronism and loved every moment of it, raising his children with the same down-home cynicism.

But what a father teaches a child is rarely what the child learns, because fathers never occupy a neutral position in a child’s life; rather, their status is wrought with admiration or fear (usually, both). So, what fathers teach falls rather in the category of information kept at arm’s length, the kind that is thought about as one thinks about a thundercloud. So it was with N.C. and Andrew: their relationship was, fittingly, rather less like that of a writer and reader and more like that of an artist and a vista. N.C. tried to imbue in his son a love for romance and adventure, but Andrew’s inner life was totally incongruous with old-timey American drama. He lived, after all, among the bleakly beautiful fields of Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, and Cushing Island, Maine.

If N.C.’s fields were vibrant and full of magic, Andrew’s were barren and melancholy.

Andrew was raised an artist and accordingly trained to pay attention to his environment; but his bucolic environment, in turn, taught him to direct his attention inward. The best part about childhood is realizing that you are uniquely alive; the best part about growing up is realizing that everyone else is uniquely alive, too, over and over. It was against these external realizations that Andrew, a melancholy cog in the generational machine, began working his way out of his father’s shadow and, by the same means, into the spotlight of the American art community.

For all his wisdom, N.C. was hardly immune to pride and jealousy. As Andrew’s early work began to spark serious discussion in the art world for his stark, sparing compositions, N.C.’s own work took a distinct turn for the meditative, with such melancholy late career (1940s) rural works as Nightfall (1945). At an October N.C. Wyeth retrospective at the Portland Museum of Art, the curator noted that this phase “represents a form of competition with his son Andrew, whose reputation by the early 1940s was increasingly firmly established.” N.C. and Andrew were preoccupied with each other’s status and approval, each caught in the other’s orbit like binary stars. Fathers always want their sons to surpass them until they do; N.C. was no different.

In October 1945, N.C. Wyeth and Andrew’s nephew, N.C. Wyeth II, died as their car stalled on train tracks in Newell, Pennsylvania. After his father’s death, which Andrew called “a formative emotional event in his artistic career,” Andrew’s paintings seemed to long for infinity––not in limestone but rather in timeless fields and ghosts, in the still air that follows a harvest. N.C.’s death left a void which landed on canvas as desolate, lonely, wayward images: barren landscapes, dead trees, lacy curtains blooming in the wind, faces downcast, empty horizons and, always, distance––reaching in vain like a hand to the stars: arms stretching out for infinity, but only ever grazing it in sad, quiet moments. A son always sees himself through his father’s eyes; when a father dies, the eyes the son peers through are tinged with grief. That was how Andrew saw, so that was how he painted.

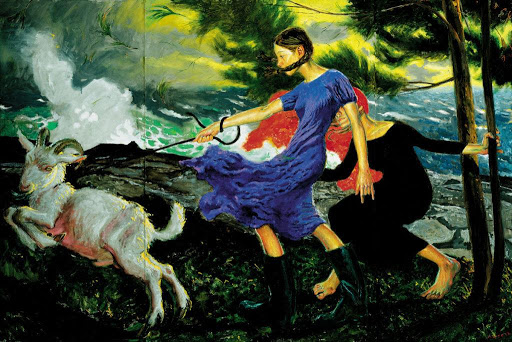

Jamie Wyeth was born in 1946, and promptly raised a painter. He was taught on a day-to-day basis by his father, Andrew, but young Jamie was known to hang out in his late grandfather’s studio. In many ways––rather more in style than in content––Jamie embraced N.C.’s love for magic and adventure, though he found inspiration mostly in the mundane rather than in historic drama. N.C. showed Jamie how drama and adventure could startle and thrill a viewer, while Andrew taught Jamie to attend to the everyday and listen for the quietest swells beneath tidal waves of distraction. An exhibit at the Brandywine River Museum described Jamie’s approach as follows: “Far from contrived, he has simply chosen to dedicate himself to an authentic depiction of the world in which he lives, and that world is the mostly unchanged bucolic landscapes of his upbringing.” Jamie tried to reconcile his grandfather’s love for adventure with his father’s love for the local and mundane, finding ways to bring out the ever-present former in the latter; see, for instance, the magical energy he evokes with two young girls corralling a goat on a windy day [below].

Jamie painted his father [below] as a man caught in a sunken place with impossible, incongruous light and life in his eyes. It’s a different kind of heroism––a far cry from the kind in the eyes of intrepid explorers that N.C. fell in love with. The wilderness Andrew was up against––an impenetrable wall of grief––could not be colonized. But what Jamie saw was his father’s quiet strength and rebellion, evident in his steadfast eyes and glowing complexion; and what we see, accordingly, is a powerful index of fatherhood.

In the past few months, I’ve visited several Wyeth exhibits along the coast of Maine. Without fail, the curators of these museums are obsessed with separation: here’s N.C., here’s Andrew, here’s Jamie. The exhibits really ought to focus on the magnetic attraction and repulsion in the white spaces between the paintings: the unmasked face of the force we call family. Art families are more than just families of artists; they’re clumps of stars making accidental constellations only visible from lightyears and generations away. The effect calls to mind the Compson family in William Faulkner’s Absalom, Absalom!, and Faulkner’s particular description of how their lives intersect: “…you are born at the same time with a lot of other people, all mixed up with them, like trying to, having to, move your arms and legs with strings only the same strings are hitched to all the other arms and legs and the others all trying and they don’t know why either except that the strings are all in one another’s way like five or six people all trying to make a rug on the same loom only each one wants to weave his own pattern into the rug….”

To extrapolate Faulkner’s metaphor, it’s as if the Wyeths were all painting on the same canvas but couldn’t agree what to paint––much less what shade of what color to paint it in––and in the process accidentally painted something shapeless and intangible: namely, the way a father looks at his son, and the way his son looks back.

Leave a Reply