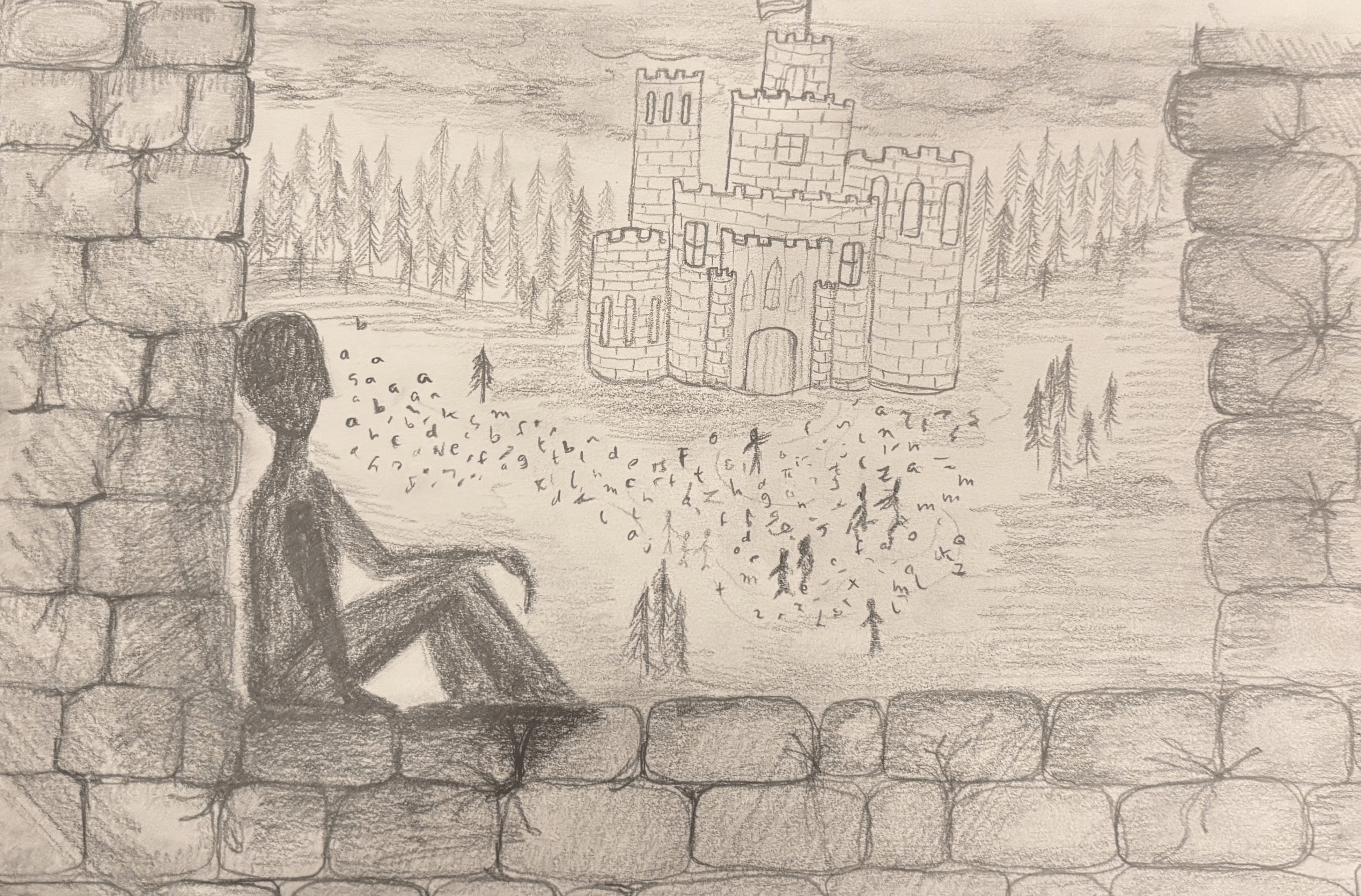

My body forms triangles and rhombuses in the negative space between limbs and sill, my back leaning against one side of the window while my toes push into the other.

There is no screen, and I’m warm from sun that doesn’t quite reach my face, as I’m still sheltered by the awning of this opening in the castle wall, this threshold between my work: the computers, the Python scripts and the proteins and the endlessly running programs, and the vast countryside of South Bohemia — the mountains in the distance covered in a dark green tapestry of trees, the bright blue sky overlooking the field of wildflowers that bound the castle gardens below me.

Out past the terrace under me is a fountain, the constant rhythm of its stream punctuated by the shouts and laughter of children; Ukrainian refugees playing in the surrounding fields, calling out to each other in a language that, while now familiar to my ears, is still meaningless.

Language barriers are supposed to be isolating. They leave you separated from everyone, unable to understand or to be understood. But no talking means no need to perform. No pressure to be interesting, funny, and polite; to ask the right questions and have the right answers; to explain who you are and what you’re doing here and what you want to do with your life.

It gives you time to think. To be with your thoughts, uninterrupted. The shouts of the children below act as background noise to the words in my head, rather than a story for my brain to follow.

Earlier that morning, I had gone on my daily walk around town. I was watching cows graze in the fields and admiring the mountains behind them that surround the town of Nové Hrady, my home for the past couple months, when an older woman greeted me. “Dobrý den!” I replied, unreasonably proud of the simple phrase that was one of few I could confidently speak in Czech.

My ears were soon filled with the sounds of hard consonants and staccato syllables as she began to converse with me, not knowing her words were nothing more than a rhythmic clicking to me. I interrupted her as soon as I could to explain that I can only speak English, and she let me continue on my way with a simple apology.

As I walked on, I felt the strange relief of not being understood — free from the responsibility of exchanging small talk with passersby, and from the need to explain myself; to her, I could be anyone. She didn’t know where I was from or why I was here, and I couldn’t answer her questions, real or imagined, even if I wanted to.

This lack of understanding is in many ways comforting. It gives me space to breathe, away from scrutiny and expectation. Yet it also imparts what can only be described as an overwhelming feeling of loneliness. There aren’t many people to talk to in the castle, and fewer still that understand me. The town is small: there are probably the same number of cows as there are people.

But I’ve learned to live in this loneliness. The sill is wide enough that there is space for my book to lie to the right of me, splayed face down, spine bent in the middle, so I won’t forget my page. My journal hides under my legs, pen resting on top, low on ink from filling too many pages with too many thoughts that have nowhere else to go.

This solitude offers a form of safety. I don’t know the answers to most questions I am asked. I’m unsure of most things I do. Sometimes I get overwhelmed by even the simplest social interactions. Even when people speak the same language as me, I somehow find myself still being misunderstood.

My friend once told me that my spirit animal would be a canary because I talk so much. It’s funny, because no matter how much I say, I never seem to get across what I truly mean. And when it really matters, my brain moves faster than my mouth, and I get stuck. My thoughts spiral and spin, making figure-eights in my mind, while my tongue remains frozen.

I can’t tell, exactly, but I think I prefer not being understood to being misunderstood. Maybe it’s better not to talk at all than for what you say to be interpreted wrong, for your voice to betray your mind.

As I sit on the sill, straddling the world outside the castle, where I am safe from these inquiries and from the pressures of even simple conversation, and the world inside the castle, where English ties me to expectations of articulation, intelligence, and engagement, to know who I am and what I want, I feel suspended in a liminal space.

Between freedom and obligation. Between a world where I can be whoever I want or nothing at all and one where I must be ready to define myself, over and over. Between solitude and scrutiny. Between my thoughts and my words.

Someone calls my name from the kitchen, a room over from where I am perched. It’s English — familiar, heavy.

For a moment, I wish I didn’t understand. That the sound could stay distant, untranslatable.

I hop down from the sill and go back to work, leaving the window and the outside world behind.

Leave a Reply