I left the theater after seeing One Battle After Another struggling to catch my breath. Writer-director Paul Thomas Anderson advances the plot at breakneck speed, collapsing the film’s nearly three-hour runtime into what feels like one long action sequence. I watched former revolutionary Bob Ferguson’s (Leonardo DiCaprio) journey to save his daughter Willa (Chase Infiniti) from his old nemesis Colonel Lockjaw (Sean Penn) with my eyes glued to the screen. Put plainly: this movie had me completely captivated, from beginning to end.

My Letterboxd review: 4.5 stars. I loved it — no one is surprised.

From the first few minutes alone, I knew that One Battle After Another would be the kind of movie I can’t help but love –– a category I call the “revolution flick.” I think of Aaron Sorkin’s The Trial of the Chicago 7 and Shaka King’s Judas and the Black Messiah — modern Hollywood blockbusters portraying radical organizing.

One Battle After Another tells the story of the fictional far-left militant group, the French 75.

In the opening scenes, we are introduced to the group in its heyday. Bob, then known as Pat Calhoun, and Willa’s mom, Perfidia Beverly Hills (Teyana Taylor), orchestrate a mass breakout from a detention center and carry out attacks on banks and politicians’ offices. Though the French 75 is Anderson’s own invention, it is clearly modeled after American radical groups of the sixties and seventies.

I can’t help but feel like my historical interest in and political sympathies for these groups make me the exact target audience for movies like One Battle After Another. Without fail, I’ll buy in, watching on tenterhooks as the activists on screen fight against injustice — cheering at their successes and lamenting their persecution. But once the credits roll and the feelings fade, I’m left wondering: what did it really mean?

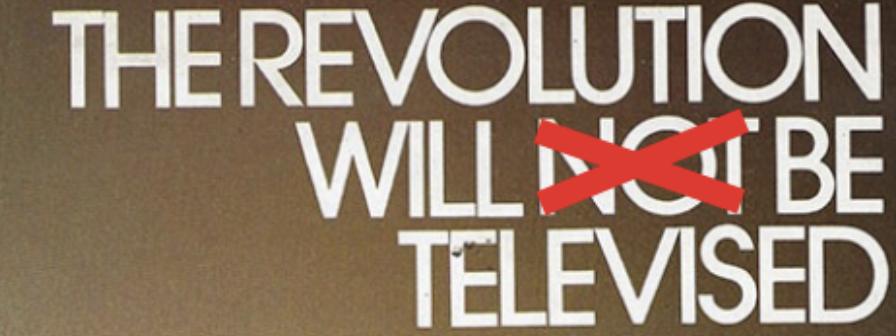

Members of the French 75, in their prime and sixteen years later, identify one another with lyrics from Gil Scott Heron’s “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised.” At Willa’s high school homecoming, she is approached by her dad’s former compatriot Deandra (Regina Hall), who intones steadily, “Green Acres, Beverly Hillbillies, and Hooterville Junction.” Hesitantly, Willa replies, “Will no longer be so damn relevant,” having been taught the code by her dad.

When I caught on, I smiled, like I too was in on the mission, and when the song played with the credits, I mouthed the lyrics.

The revolution will not be televised,

The revolution will be no re-run, brothers,

The revolution will be live

Then the irony dawned on me — the revolution has indeed been televised, and I loved it. At 7:30 on Saturday night, I watched it on the big screen at the Garden Theater. I paid eight dollars for three precious hours of radicalism turned cinematic. The revolutionary movements that inspired the French 75 are broken down and reconstituted into a compilation of high-adrenaline moments: a stunning car chase, the nauseating view of undulating asphalt, a bomb going off, a tearful reunion.

I will not deny that One Battle After Another is well-made, well-written, and well-acted, as most revolution flicks are. Smart, snappy, thrilling, and at times touching, these movies manage to exalt their heroes without necessarily promoting their politics.

Granted, it would not be fair to call Anderson’s film wholly apolitical. The depiction of Colonel Lockjaw and the white-supremacist Christmas Adventurers’ Club to which he hopes to gain entry is a clear satire and biting critique of far-right movements in the United States. Sergio, a friend of Bob’s, is a leader of the undocumented community in Baktan Cross, and is portrayed as the caring and essential community organizer that he is.

But the fact remains: while One Battle After Another is a movie about revolution, it is not revolutionary. Revolutionary movies are a part of the movements they depict. They themselves are political weapons. Revolution flicks, on the other hand, are still primarily objects of entertainment. As Richard Brody writes in his review for The New Yorker, Anderson’s film is “a work of grand symbolic design.”

I am not prepared to say that revolution refracted through the lens of Hollywood is wrong. I do not think that all films about revolution need to be dogmatic or propagandistic. We should remember that movies are, after all, works of art. But, when the lights are down and the music is loud, when we feel our blood grow hot in defense of the agitators on the screen, we should remember that movies are also products — that identifying with activists and cursing the establishment only when the lights are down is not a revolutionary act, but a marketing job well done.

Leave a Reply