Gene Mitchell spends over 200 days abroad each year trading fossil fuels and other dry commodities for his day job. Business has taken him to fifty countries on six continents in twenty-five years. Wherever he goes, he runs.

He has run through Gorky Park in Moscow, Hyde Park in London, Tiananmen Square in Beijing. He ran through the wide streets of Varna, Bulgaria just after the fall of communism in the mid 90’s. (Communist and ex-communist countries tend to have wide streets, he has learned.) Varna’s economy was in shambles and its inhabitants drank heavily. There were no police. A drunk driver tailed Mitchell on one of his early morning runs and drove him off the road.

On a 6am run in Cali, Colombia, where Pablo Escobar had recently relocated his cartel headquarters from Medellín, Mitchell saw a man shot and killed. His mental response: stay alert. On Isla Rosario, a small, densely-jungled island off the coast of Cartagena, his running options were limited. During a two-hour break, while his colleagues were unwinding with cocktails, he headed off through the undergrowth toward the beach. He soon encountered an impassible rock point. He took off his shoes, waded into the water, and swam around the point, holding his shoes aloft. He arrived on shore, put his shoes on, and ran back and forth on a short strip of beach for eighteen miles. When he started, no one was there. Soon a young child appeared. By the time he finished, about twenty-five locals were watching. “¡Corre Gringo!” they chanted.

He ran the day his father passed away from a heart attack. He ran on September 11th, 2001. That day, he landed in Brazil at 5am and learned about the attack from a hotel porter. Twenty residents of Ridgewood NJ, where one of three running stores he owned at the time was located, died in the attack. Three families lost both husband and wife. He shut down his stores for the day. “It was a pretty solemn period,” he says. But he ran.

—

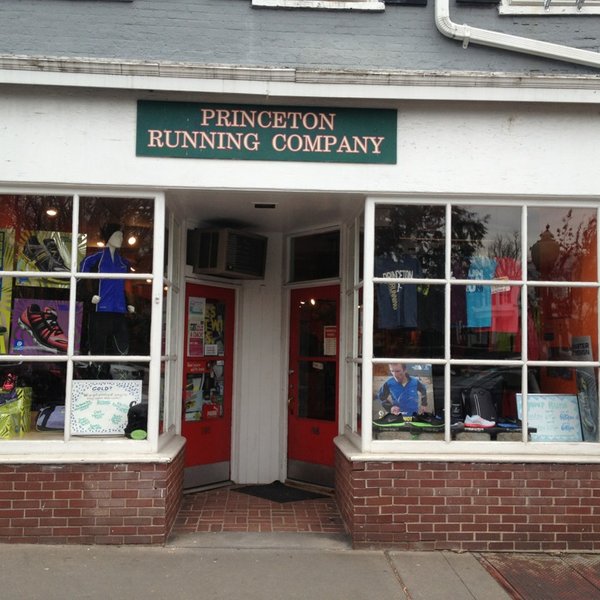

In the late 90’s, running shops were, by and large, destination stores. They chased low rents and relied upon advertising to attract customers. Mitchell thought this was a mistake. Running was becoming more mainstream and money other companies spent on advertising could be better spent on rent in high traffic areas. So in 1996, at the age of twenty-nine, with a full-time job and training schedule, he started the Princeton Running Company with one idea in mind: “Put it right on the fifty-yard line.” His first location, on Nassau Street, cost $8,000 a month—roughly four times as much as most competitors were paying.

In the final hour before Mitchell opened the Nassau street location, his business partner—a successful running store owner—backed out. Mitchell did not know the running business. And his ex-partner had over-ordered. Rather than declare bankruptcy, Mitchell opened another high-rent location in Ridgewood, NJ, where he transferred half the merchandise. Both stores flourished, and Mitchell saw that his real estate insight was gold. He opened New York Running Co. in 2007 in the Time Warner Center, which cost him well over $1 million each year in rent—an amount that far exceeded what any other independent retail running store had ever paid.

Mitchell came up with creative solutions to old inventory problems. He began to store merchandise in his house in Franklin, NJ. Soon his entire basement was filled with shoeboxes; then the living room, then the dining room. Then three of four bedrooms. “It was really, really efficient,” he says. “Our stores never ran out of anything. Period.” FedEx trucks delivered new merchandise to the house on the hour. One day a truck left four or five half-naked mannequins in the driveway. Neighbors complained, and the company warehouse was decommissioned, restored to its strictly residential functions.

Time and again, Mitchell innovated to cut time and costs. He bargained with shoe vendors for a flowing inventory arrangement wherein the Running Company could pull merchandise from vendor storage at will. “Almost every running store today seeks that type of buying structure, and we were doing it fifteen years ago,” said Ben Cooke, former Operations Manager for Princeton Running Company and current VP of Fleet Feet Sports.

Mitchell negotiated hard with shoe vendors. He enjoyed it as he would a sport. Once, in a negotiation in Indianapolis, Mitchell stood up and left the room. “Just walked out,” recalls Cooke. He came back an hour or two later with his head completely shaved. His opposition interpreted the move as a sign that he would be hard to pin down. “Is he just that smart, that he knows that he can flip you out? Or does he just think so differently that he does things accidentally that just are somehow brilliant?” Cooke is not sure. “That’s the mystique of Gene.”

—

In 2007, Mitchell qualified for the Olympic Trials for the first time in his life, by running the Chicago Marathon in 2:20:48—five minutes and twenty-two seconds per mile. He was about to turn forty years old. (The average age among competitors at the 2007 Trials was twenty-eight.) He was working seventy hours per week and traveling around the world for his day job, managing the fledgling Princeton Running Company on nights and weekends, and running a hundred miles each week. This was the year Runner’s World Magazine dubbed him, “The Man Who Does Everything.”

He did not show particular promise as a young runner. “I don’t think he’s loaded with talent,” said his old running coach, Jim Schlentz. After a lackluster career at Pascack Hills High School in Montvale, NJ, Mitchell managed to walk onto the varsity team at Villanova University. He improved enough to earn a full-scholarship fifth year, during which he won a steeplechase title at the 1990 Big East Championships. “He’s one of those rare individuals who probably used ninety-eight or ninety-nine percent of all his talent,” said Schlentz, who began working with Mitchell after he graduated. Schlentz did not have to motivate Mitchell. He had to rein him in. “He was running too hard,” Schlentz recalls. “We slowed him up in practice.”

Having qualified for the Olympic Trials, Mitchell did not run. On the results page, his name is one of four clustered woefully at the bottom, below those who finished the race or voluntarily dropped out mid-way. One of the other three was hit by a car a few weeks prior. Another had a direct work conflict. The third started the race but collapsed five miles in and died of cardiac arrhythmia. No such problem for Mitchell. In a move that puzzled the US running community, for whom the Trials represent the domestic pinnacle of the sport, he chose instead to run the New York City Marathon—which geographically intersected the Trials course, and which took place the very next day.

“I wasn’t going to be competitive in that race,” he said of the Trials. “There was probably an eighty percent likelihood that I would be in the back twenty people.” To him, a low placing would overshadow the honor and pleasure of participating. Meanwhile, he thought he had a shot to win the masters division of the New York City Marathon. (He placed a disappointing fifth.)

As he used to tell his Running Company employees, “If you’re not moving forward, you’re moving backwards.”

—

Mitchell is not one of those geeky looking distance runners of stick figure proportions. He has a strong, wide build and a chiseled face with cotton-white stubble and deep-set blue eyes. He is casual—his wardrobe consists of T-shirts and khakis—but serious. When he does smile, it is a goofy, involuntary grin that reveals a twisted tooth.

Mitchell married his second wife, Angie, in 2009. They met two years earlier through a mutual friend at Koch Industries, where Mitchell worked and Angie had recently left. They spent those two years commuting back and forth to see each other. Things have not changed much. “We literally will draw out maps and calendars and schedules on napkins to figure out where we are each going to be, and how to stay in communication,” she says.

Mitchell’s focus on work does not bother his wife. She shares his priorities. The two own and run several pubs and restaurants together, including Kelly’s, a popular bar among Villanova students. The Garrett Hill Ale House, another of their local ventures, boasts over 100 craft beers. Despite this array, Mitchell’s tastes are simple: his favorite drink is Coors Light. He likes the taste and appreciates its accessibility. He also likes that he can put away five or more of them on nights out. “I’m an all or nothing guy,” he admits sheepishly.

A decade ago, Mitchell and Angie named one of their pubs Flip and Bailey’s after their two dogs. Now they have Carolina and Ginger. “They’re like our kids,” said Mitchell. Carolina is a rescue dog. They found her on the side of a highway in North Carolina and thought she was dead. Ginger is a well-fed lab. On a table in their backyard lies a threadbare burlap sack filled with about thirty grubby, saliva-coated tennis balls. Mitchell keeps about five-hundred more in his basement. Half of the year, the local tennis courts are littered with stray balls. He runs by and stuffs half-a-dozen in his pockets every morning.

—

On a rainy November day, Mitchell was out for a run. He was sore and tired from a workout the night before. “You feeling good today, huh Freddy?” he said. “You’re killing me.”

Fred Klevan is Mitchell’s best friend and business partner. Fifteen years ago he set the American 10k masters record in 30:25. He has completed the Kona Ironman four times. He met Mitchell many years ago after a race and before setting out on an 80-mile bike ride. “He probably thought I was a freak,” recalls Klevan. “Well, we were freaks.” Now Klevan was one-stepping Mitchell, pushing the pace.

Mitchell and Klevan are both in their fifties. They spoke of chiropractors, cryotherapy, the Graston Technique.

“Was this the woman you know?”

“Yeah.”

“Did it feel weird to have her doing that on your butt?”

“Yeah.”

They ran by the tennis courts that, in warmer months, sustain Mitchell’s tennis ball cache. Klevan made a bathroom stop. Mitchell took the chance to breathe. He was running the same loop he had been since his Villanova days. He used to do four laps, about 9.25 miles, on hour-long easy runs. Since an injury several years ago, he does three. A serious runner knows his daily route like the sinewy contours of his own legs. He knows what every split means and how each section ought to feel; reflexively compares incoming data to an internal database to calculate current condition. Mitchell knew exactly how fit—or unfit—he was. “Nothing you can do about it,” he said, breathing heavily. “But it’s frustrating.”

—

“Would you rather be able to teleport, or never sleep?”

It is a question Mitchell and Ben Cooke, his former manager of operations, used to ask each other in the early days of the Princeton Running Company. They could not teleport, so they chose not to sleep. When Cooke visited the New York location, he opted to sleep for a couple of hours in the store rather at a hotel, which would cost the company the equivalent of several days of labor. “That was the culture Gene created,” he recalled wistfully. “We were on a mission, frankly.” Mitchell’s first marriage fell apart during this period. “The business became the priority instead of family, and that’s a mistake,” Mitchell admits. But all things considered, he remembers the time fondly. He was surrounded by people he respected, swimming in top-of-the-line running products. “I was like a kid in a candy shop.”

By 2011, the Running Company comprised eighteen stores and generated $19 million in annual revenues. It had become the largest buyer of running goods from Nike, Saucony, and Brooks in the country. Management was extremely lean, and the organization was flat. “Owned and operated by runners for runners” was the tagline. Mitchell believed his greatest asset was the passion of his people.

He was not a loud, charismatic leader. He did not stand on tables and give speeches. He was not even physically present most of the time. But Mitchell was fun, and he cultivated a sports team culture. He would organize group races and retreats every year. “We had some wild times,” recalls Cooke. “We had a management meeting where we rented two houses on the Jersey shore.” But Mitchell never lost sight of the goal. “We could be up drinking until 3am, and he’d want to run at 6.”

Then, somewhat abruptly, Mitchell sold the company in 2011.

“The running business was his baby,” gushes Cooke. Mitchell says he thought the buyer could improve distribution. Souring relationships within the company may have been a factor. Perhaps he was tempted by the big payday. Maybe he finally got tired.

It was agreed that in the aftermath, Mitchell would remain President and quit his day job at Koch to work full-time. But those plans fell through. “It was a disaster from the day of the closing,” he recalls. The new execs instituted a top-down hierarchy. They cut wages. The best employees, including Cooke—the people Mitchell believed made the business—moved elsewhere.

“There were people flying in on private jets,” recalls Mitchell. “These guys didn’t run. They were in suits…. I shoulda known.”

Then Mitchell left to work full-time at Koch Industries.

—

Mitchell left Koch in 2014 to become Global Director of the Dry Bulk Division at Tricon Energy, Inc. He primarily trades petroleum coke, which is a compacted version of what is left after all the more valuable products have been extracted from crude oil. Petroleum coke is used to make concrete or burned for power. When burned, it releases more CO2 than coal.

He is very good at his job. His team loves him. “He’s one of those guys where you give him two and he gives you back five, and you give him seven, and he gives you back twenty,” says Tricon founder and President Ignacio Torras. As with Coach Schlentz, Torras’s only challenge with Mitchell is reining him in.

Mitchell loves his current job. He loves that, by his estimation, about eighty percent of petroleum coke purchasers globally know him by name. He loves that he has developed a specialty that makes him valuable. He enjoys having clear goals. He deeply values relationships with co-workers. A quote on Tricon’s website—“Every ceiling, when reached, becomes a floor”—is something he could have written. He sees this as his last stop on the tour.

The travel is, for the most part, not fun. He has meetings all day. He lives on four-and-a-half hours of sleep per night. Out of dietary restraint, he generally does not explore the local cuisine. He does most of his exploring while running, though it is not clear that he sees it as such. Still, in the twenty-five years he has been traveling, he has seen parts of the world change dramatically. He used to run around Tiananmen Square at 5am to avoid swarming cyclists. Now he can wake up at 6:30 or 7 because no one bikes anymore; everyone drives. But Mitchell has observed a tradeoff. “The pollution is an issue. And it’s getting worse, unfortunately.”

That the pollution is, in a small but direct way, caused by the product he is there to sell is not something he has given a lot of thought to. He sees this line of thinking as a distraction, something to push through. “He’s more intrigued with the trade and structure,” says Angie. “The commodity itself, and the connection with health, and his other passions…” she paused for a moment. “On that level, you just won’t see it.”

—

In Mitchell’s home office hangs a bird’s eye photo of a loaded freighter passing under a peloton of runners on the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge. Mitchell is one of fifteen figures in the pack, which, less than two miles into the 2004 New York City Marathon, has already broken away from the tens of thousands of less competitive participants. The freighter—red and massive, with froth peeling off its prow—moves, like Mitchell, powerfully and unequivocally forward, but it moves along a colliding vector. According to Angie Mitchell, there is a good chance its brightly colored shipping containers hold fossil fuels that her husband had bought and sold. She framed the photo and gave it to him for his birthday. Below the photo is a magazine quote from him that says:

You Cannot Stagnate.

If You Are Not Pushing Yourself,

You Are Moving Backwards.

-Gene Mitchell

In the corner of Mitchell’s office is a guitar he does not know how to play. He won it in a race. His back desk is littered with trophies, also won in races. Through his office window a large American flag waves on his front lawn. It is the biggest flag on his block.

When Mitchell completed his loop that November morning, he ran right past the flag, and his house, with dogs and wife inside. He was looking at his watch, waiting for it to read “1:01:13.” He had been running for an hour, but that was not quite long enough. “If you’re running an hour, run an hour and one minute. It’s like running through the line,” he said. As for the extra thirteen seconds: he has to run through the second line. Thirteen is his lucky number. “It’s stupid,” he admitted.

Time is important to Mitchell, insofar as it limits his ability to accomplish things. He wants more time to do things, and to do things in less time. He recently turned fifty, which he did in the same amount of time as everyone else. With his eye on his watch, he ran past a small yellow street sign with black letters that read “No Outlet.” He ran towards the dead end.

Leave a Reply