Douglas Coupland’s exhibit in the Vancouver Art Gallery this summer was called “everywhere is anywhere is anything is everything,” and from the instant I saw the title, before I even set foot in the museum, I was not feeling it. The all-lowercase aesthetic felt, to me, like an appropriation by a pretty square art gallery and a not-young man of a look that coded for “youth” and “hipness.” I was also irritated by the title’s total sincerity. I couldn’t believe anyone who’d emblazoned such an inanity on a poster in a hip font hadn’t realized it sounded like something only someone baked out of their mind would ever say without realizing how stupid they sounded. But maybe that was because they believed what the posters seemed to suggest: the Messiah, Douglas Coupland, had returned to tell Generation X What Was Up with the Kids these Days.

Coupland is an author-cum-artist whose greatest achievement perhaps is popularizing the phrase “Generation X” in the 1990s to describe the various traumas and pains Baby Boomers were experiencing. The exhibit’s (incorrect) claim that Coupland invented the term (it was invented by a photographer named Robert Capa in the early 1950s) bolsters my original impression of him: he’s a jerk whose pomposity has been allowed to define a generation. I went to the exhibit with my father, a baby boomer and English teacher with a PhD and a serious Marxist streak who was almost tweaking off the four espressos he’d already consumed by 11 am that morning. As we moved through the rooms of the exhibit, which took up the entire first floor of the Vancouver Art Gallery, I slipped deeper and deeper into an alienated funk as my very intelligent but irrevocably middle-aged father became more and more certain of Coupland’s gift. But I’d like to think my feeling of alienation wasn’t because I am defined by my devices, but because I’ve spent a lot of my life being talked at by middle-aged men about all the ways I am worse off than they are. As surprising as this may be to Coupland, the more he rambled about the decay of my brain, the more unimpressive I found his.

It wasn’t all bad. There were some really cool pencils arranged to evoke the seasonal color palette of Canada in spring, summer, fall, winter. It simultaneously reified and deconstructed the artistic process while nodding to commodification of the art-object that happens on all kinds of social media, the Pinterest-y fetishizing of the art-creating-thing and not art itself, the pictures of immaculately arranged crayons that suggest creative potential but do not actually show creation. In that room I had a revelatory moment of understanding my consciousness’ deeply capitalist hue and how programmed I am to understand the unused good as perfect for its lack of use, and how this will make me always want the new, untouched, pristine thing and spurn anything my grubby human hands have touched, even if it was in order to create beauty. Thus preoccupied, I wandered into the next room, where there were two separate platforms bearing Lego creations, one with fifty of the exact same perfect Lego house and the other filled with all kinds of unique and individual towers of Legos, multicolored and various and complex. Coupland constructed these towers out of smaller towers fans had built at an event and—in contrast to the Levittown next to it—it was almost thrilling. To me, it seemed an illustration of the potential of the human mind when given adequate resources and allowed to roam, not confined into little boxes. Then my middle-aged quasi-Marxist father wandered in and my trouble began.

“Ah,” my dad said, looking at the towers. “Chilling.” I liked it, I objected. “It’s about the minimization of the modern man,” my father continued, “how man is dwarfed by urbanization.” No, I said, I didn’t have such a pessimistic reading, it’s beautiful, it’s inspiring, it’s about what humans can do with their minds and their hands if they want to.

My dad was unconvinced and it made me furious. I know there’s not a right way to interpret art. I know my father is allowed to like whatever art he chooses. I’m alive in the twenty-first century and I know there is no truth and everything is interpretation and art is trash and trash is art, etc, and part of the reason I know this is thanks to my father, who is a very educated and intelligent man with exceptional taste and I owe much of what I know about literature, art, and culture, (including the futility of interpreting it) to him. But something about the exhibition felt so personal, so targeted at me—at you, reader—at twenty-somethings, and so little of it gave us a chance to respond, that my father’s siding with Coupland, his peer, instead of me, his daughter, made the whole experience even worse. I was the one inheriting the world that made my father and Coupland despair; but somehow I was the one whose experience of this world was least relevant.

Thus disagreeing, my dad and I wandered into the next room, and it was here Douglas Coupland lost me forever.

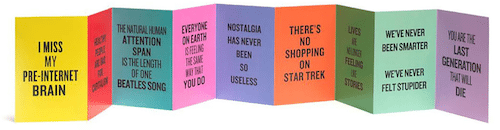

This room’s walls were covered in brightly colored posters—green, pink, yellow, purple—each bearing a different black block-lettered slogan in all caps asserting something about what technology does to a human, almost all of which failed to say anything that David Brooks hasn’t already. Characterized by the pessimistic, condescending tone that most baby boomers assume when talking to “millenials,” Coupland’s called them “Slogans for the 21st Century.” “You are the last generation that will die,” I read. “Lives are no longer feeling like stories,” “Once the internet colonizes your brain it can never be decolonized.” I stared at a few of the signs in disbelief and tried once again to articulate to my father how inadequate these were as an attempt to say anything about the Internet and Internet culture, but he was too busy taking pictures of the posters with his iPhone to hear me. For my own, millennial part, my phone was deep in my pocket. It was only when I found everyone around me unreceptive to what I had to say that I started to tweet about it—at least people on the Internet would listen to me. (Note: these sayings also translated excellently into T-shirts, mugs, and greeting cards for sale in the Gallery’s much-lauded gift shop, displayed prominently to all visitors.)

In another room, a placard that began “In examining the current condition, Coupland has consistently taken an interest in current events” (though surely a curator and not Coupland is to blame for this particular string of inanities) informed me that this crop of canvases was “meant to be viewed through the lens of the smartphone,” no doubt Coupland’s way of rolling his eyes at the “smartphone age,” as—haven’t you heard—that’s the only way we look at things these days, anyway. Convenient for the artist’s point about the ubiquity of smartphones and our own inability to put them down, then, that his exhibit demanded the devices emerge in order for the artwork to be understood as the artist wished it to be. In addition, the ruse didn’t even work: the pictures were not more clear when looked at through the smartphone, but the sight of a gallery full of people looking at art through smartphone screens will certainly provide a chilling illustration of the decay of the modern age to anyone who wishes it.

I’m not trying to deny that there are issues with contemporary society, nor am I trying to criticize art that criticizes. That’s what art is for. I am rejecting, however, the established and tenured and usually male voice I keep hearing—whether it’s Brooks, William Deresiewicz, Coupland—that just whines and whines and whines at me about how different things are now. Part of the reason these men are cranky is that they can tell they’re losing control of a world that they once ruled, a world where everything that happened made sense to them and everything fell into a particular pattern, as things had fallen for ages before. Though human interaction with its technologies presents challenges, it’s important we don’t forget how the formidable a democratizing force the internet is, one that gives us access to voices we would never have known if the world Coupland is so nostalgic for had persisted unchanged.

In reaction to this belligerent pessimism, I’ve adopted a steely optimism: I refuse to despair and I refuse to operate in a world that I think is getting worse. I know that conducting my social life in large part through my phone makes me more awkward in real life social situations, I know that being able to be constantly amused has fractured my attention span to bits, I know that there are many things that used to be very good in the world that are now very bad, but I can’t help but suspect that there are a variety of soul-searching, philosophical, beautiful, piercing, and most importantly original works of art about the internet one could make if one were not a middle-aged white male deeply immersed in the establishment, and I am sick of that perspective being the only thing I see or hear in these cultural, consecrated settings. To recognize that we live in an age in which our ways of experiencing and understanding culture are changing more rapidly than ever but not allow those for who culture has changed most significantly to speak flabbergasts me. On the Internet, I’ve reblogged and read and otherwise interacted with—in a real way, not a superficial one—a lot of thought about what it means to be a person living in a “technological age,” but in these pantheons of culture, it is nowhere to be seen.

The last room of the exhibition—which was a room filled with junk Coupland had collected over the years, a nice touch from a man who had just chastised me and my generation severely for our own self-obsession—was meant to be Coupland’s brain. It was a highlight. I actually enjoyed it, in the way that humans always have and always will be drawn to the very specific and individual, because that is why art is hard and why it is worth doing. You cannot distill the complexities of what it means to be on this planet on a t-shirt and be done with it. While it is nice for Coupland and his career and his pocketbook that many in his generation agree with his rendering of the modern world, there are those for whom that world is not a disappointment. The rest of the Vancouver Art Gallery was filled with fascinating and innovative art that combined all kinds of modern technologies—sound, robotics, light shows—to create gripping, interactive immersive experiences that thrilled me. I was also thrilled by a few of the classic, old-school paintings, because they too were intensely specific and/or realistic recreations of a moment in time or an experience of the artist, not a caricature. It is a shame that Coupland is given free license for this nonsense because he appropriated a term, once, and that a very good museum has to fill itself with his blathering. What is good, though, is that the technology he despairs of is exactly what enables me to write this, to fume, though I am not a middle-aged white man and no museum is interested in my own personal collections of crap, and I’ve never in my life thought so much of my own self as to actually really think that “everywhere is anywhere is anything is everything” No: I know that the anywheres are different from each other, as are the anythings, and the joy is that it is us, as humans and as artists, that get to connect them to each other, like Legos, as if we were making a wild and whimsical tower.

Leave a Reply