This short story was written as part of an ongoing project funded by Princeton’s John C. Bogle ’51 Fellows in Civic Service program.

This week, Andrew likes the Red Hot Chili Peppers. His parents are relieved that his Bieber phase seems to have ended; last week, every time they got in the car, Andrew would say, “De-spa-ci-to.” And so they would listen to “Despacito” on repeat. (note after conclusion of story)

Andrew can’t talk much, but he can read, and now, sitting in the back seat, he clutches the lyrics of “Snow (Hey Oh),” which his mother printed out when he first discovered the song on iTunes.

“SNOW,” he’d told his mom at the kitchen table, playing it as loudly as his iPad would allow.

“Sure sweetie.” She clicked Purchase, then Googled and printed red hot chili peppers snow lyrics. How many albums and binders they’ve filled this way: 4,012 songs on his iPad, organized alphabetically, from ABBA to Ziggy Marley, and rows of binders on his bedroom bookcase, likewise alphabetical. Within the past few months Andrew has moved from Elvis to Ed Sheeran to David Bowie to The Chainsmokers to Lin-Manuel Miranda and, finally, to Justin Bieber. He searches deliberately, informing himself about each artist by listening to at least one full album before selecting his favorite song and playing it over and over. He’s not sure why particular songs resonate with him upon first listen, but that’s part of the magic: finding, finally, one that speaks to him.

“I don’t know what Andrew gets out of this,” his father remarks, intrigued, from the driver’s seat, connecting his iPad to the aux cord. “These lyrics are nonsensical. And aren’t they about heroin?”

“Coke, I thought,” his mother replies, turning around to smile at Andrew, who is beaming quietly at the sheet of paper in his hands. He concentrates hard on following the words, not understanding them, just hitting each one as he hears it come through the speakers. He loves the bounce of it: he can pick out the guitar from the drums and move the balls of his feet to one beat or the other. The song is heavy or light, depending on which instrument he hangs onto: a weighty drumbeat, a frail warble in the refrain. Andrew wonders if everyone who hears his songs feels a form of his feelings or if the meaning of the words makes a big difference. But to him, this is a soft sort of wonder, only a little sad. He loves the complete control he has over his soundtrack.

And by not understanding lyrics, it’s easy for Andrew to hear unique renditions. Of course, many — probably most — songs are about love: being in or falling out, that type of love. No one thinks Andrew will ever have that, including Andrew himself. And so those sorts of interpretations never cross his mind when he listens. Instead he hears vague swathes of feeling: a guy getting by and singing about it. A cool tone, mostly melancholy but with definite pluck. He pays attention to how the elements seep in — the opening noises, light taps on cymbals — the tinkle of his cat’s collar, the bells on the door of diner down the street — and when denser drums roll in, they’re still mild, softly piercing the ribbons of voice which go up and down, his mother’s needle going in and out, threads cinching the song, Andrew pulling it in, closer to himself, the thick ring of guitar strings making the car speakers shiver.

But the whole song doesn’t stay so temperate. Around 1:45, the voice and drums and guitar get worked up — louder, distraught, “dysregulated,” Mrs. Q might say, if Andrew were in the classroom, sitting quietly, and something made it so that he couldn’t sit still any longer, and all he could do was jump up and yell. Usually it’s a painful throb: someone doesn’t ask him something, someone doesn’t understand something, and the frustration waterboards him, and everything is loud, so loud, and he screams. The music screams here too. It’s awful. He covers his ears. Then it moans and collects itself, getting softer and self-composed before losing it again at 3:23. Silent throughout, Andrew holds the iPad on his lap and watches the time so he can brace himself for the frenzies. Each one makes him startle a little, in the same way that gunshots might startle a moviegoer.

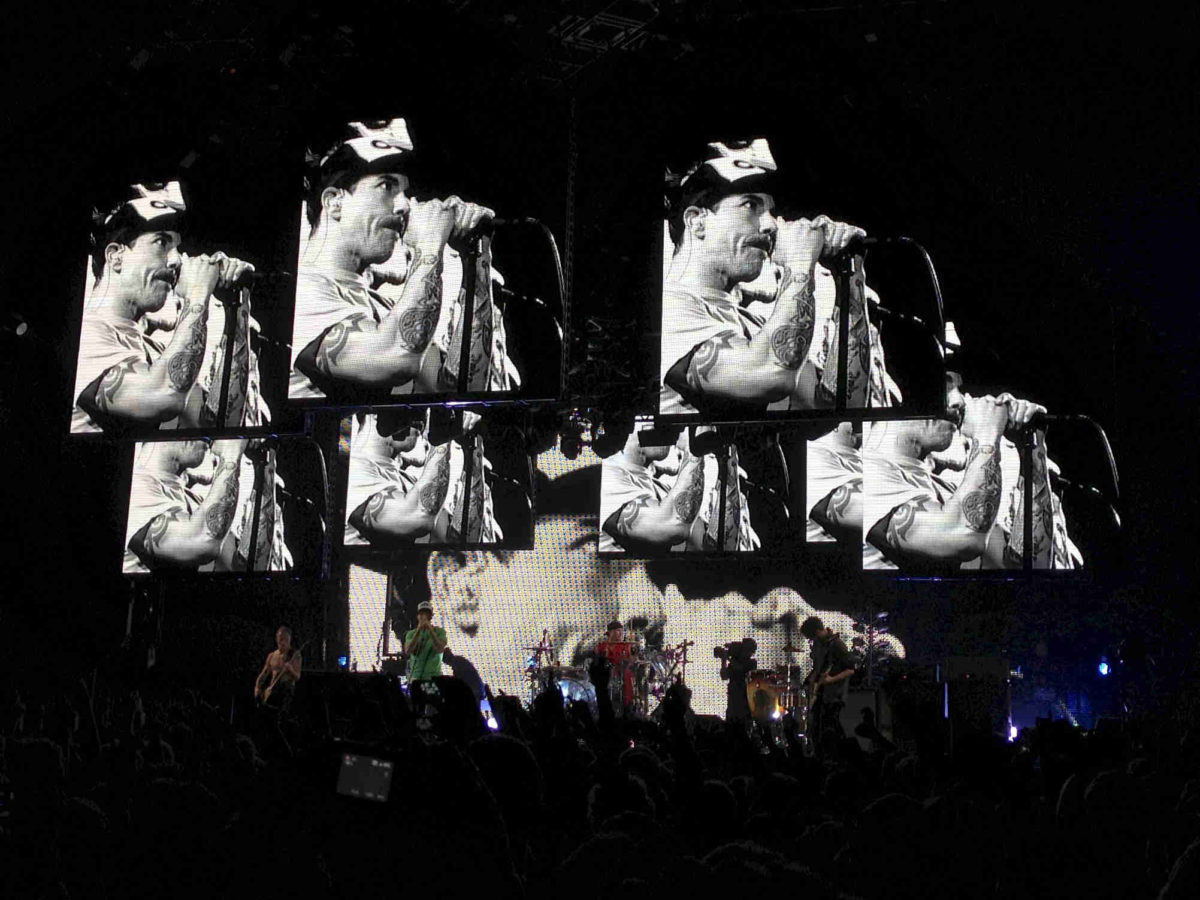

He can’t go to concerts, though. There, the gunshots are too real. They’re not just noise — they’re everywhere, ricocheting; sweaty strangers are dancing; it’s utterly paralyzing. Andrew only went to a concert once, with shrieks and strobe lights and t-shirts for sale, and even though he’s a substantial guy —5’10”, 200 pounds — he felt so much smaller than the people surrounding him. He hugged his mother the entire time, his sandy head several inches taller than hers and his big back sweaty with fear. In retrospect, he’s happy he went: now, he knows how to listen to music. He listens only when life is still. If there’s a lot moving around him, even at school, too much clashes and crescendos. But at home, he handles songs delicately. He hears them fully.

His parents sit quietly in the front seat, listening to the song, too. His father wears his weekend clothes, khakis and a blue collared shirt with the sleeves tucked up twice, and the pads of his index fingers thrum the steering wheel. Prim but relaxed, his wife crosses her little ankles in the passenger seat, blonde hair falling around her face. Their son is their entire world, and they can’t help but interpret the lyrics he’s latched onto, reasoning that, maybe, some speak to his experience:

Hey oh, listen what I say, oh. Surely sometimes Andrew feels completely silenced, shepherded along by aides and teachers according to his state-approved schedule.

But I need more than myself this time…maybe he’s lonely. He has classmates, yes, but no close friends, no siblings, just his parents.

And the more his parents listen, the more they think about the song in terms of themselves. Maybe that’s what happens when you hear a song on replay: conceit is inevitable. They think about their nonverbal teen in the backseat, and they imagine his frustration, and they feel their own: The more I see, the less I know, the more I like to let it go…

He’s nineteen, and there’s so much to sort out: the rest of his childhood and all his adulthood. ‘Post-secondary placement,’ vocation, guardianship. They feel dreadfully small sometimes, almost despairingly so, with every system imaginable against them: the Department of Developmental Services, which demands Andrew’s complete medical records by the end of next week. His public school, which does little to include sped (special education) kids in the normal curriculum. And the system that let them down most … well, it’s a weird sort of guilt, to know that malfunctions deep within their own bodies were responsible for their beautiful but disabled son.

Out of fear of autism, they didn’t have more children. They considered adopting, but Andrew was a big time commitment, and they wanted to give him their full attention. We created him, they reasoned; we owe him. They spoil him with music, clothes, food, routine, everything. Whatever Andrew likes, they do.

At night, after Andrew is asleep, his parents talk quietly about the future. They still don’t know if their nest will be empty after Andrew graduates. Is it really best for him to live at home forever? There are so many places to research: community day programs, group homes, vocational training, jobs themselves…it’s staggering, and it’s all their responsibility. They know Andrew best. They’re the only ones who understand their nonverbal son: not precisely, but deeply, delicately. They sense how he listens to songs.

The three of them sit together and watch the hot fields pass by their windows, feeling indulgently otherworldly as they listen to “Snow”—Andrew, appreciating his music, and his parents, appreciating their deep love for their son. Nothing quite compares to wordless understanding. They see broiling asphalt, deep green soybeans, silky husks of high July, and though they’re not going anywhere particularly interesting — just running some errands — the day seems bold. As they listen to Andrew’s soundtrack, things look big and bright, and they feel just a tiny bit bigger, too.

Note:

Researchers and specialists have long been intrigued by how autistic people experience music. Some studies argue that individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) are “emotionally unresponsive to music” due to the fact that the evolutionary purpose of music was to “promot[e] social bonding in early human society” (1). Since a key characteristic of autism is impaired social skills and communication, scholars like David Huron, Daniel Levitin, and Isabelle Peretz assert that autistic individuals are resistant to this social-emotional quality of music and, therefore, “deficient…in the appreciation of music” (1).

But many studies say otherwise. Preliminary research is emerging that suggests a dopaminergic explanation for why individuals with ASD do appreciate music — and, moreover, why music is perhaps even more pleasurable to them. According to a study published in Neuroendocrinology Letters, levels of a type of dopamine (DRD3) measured much higher in patients with ASD than in a neurotypical control group. Researchers concluded, “Our current results provide intriguing preliminary evidence for a possible molecular link between dopamine DRD4 receptor, music and autism, possibly via mechanisms involving the reward system and the appraisal of emotions” (2).

In a fusion of these scholarly positions regarding the autism-music connection, music therapy has emerged as a form of early intervention. Interestingly, the core concepts of music therapy align with arguments made by Allen and Heaton (1) about autistic people’s apathy toward music: according to a Cochrane Review published in 2014, “Music therapy uses musical experiences and the relationships that develop through them to enable communication and expression, thus attempting to address some of the core problems of people with ASD” (3). Music therapy organizations like Voices Together see music as a tool for communication and inclusion (4).

Academia aside, there’s no doubt that many people with ASD love music. Each parent interviewed for this book has spoken fondly of his or her autistic child’s taste in music — including the individual who inspired this story.

Works Cited

(1) Allen, Rory, and Pamela Heaton. “Autism, Music, and the Therapeutic Potential of Music in Alexithymia.” Music Perception: An Interdisciplinary Journal 27, no. 4 (April 2010): 251-61. Accessed July 20, 2017. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/mp.2010.27.4.251.

(2) Emanuele, Enzo, Marianna Boso, Francesco Cassola, Davide Broglia, Ilaria Bonoldi, Lara Mancini, Mara Marini, and Pierluigi Politi. “Increased Dopamine DRD4 Receptor mRNA Expression in Lymphocytes of Musicians and Autistic Individuals: Bridging the Music-Autism Connection.” Neuro Endocrinology Letters 31, no. 1 (2010): 122.

(3) Geretsegger, Monika, Cochavit Elefant, Karin A. Mössler, and Christian Gold. “Music therapy for people with autism spectrum disorder.” Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, June 17, 2014. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD004381.pub3/abstract;jsessionid=3231D142C64CFDF0B6103F77525C667A.f03t02.

(4) Voices together. 2017. Accessed July 21, 2017. http://voicestogether.net.