The reader has surely known a scrawny, gangster-loving seventeen-year-old boy who fangirls over the King of Cocaine. Bring up his name and they can educate you on how he built his empire and became one of the richest, most powerful men in the world—and it doesn’t stop there. No, no, no. They know the fun facts too. They’ve watched the series, they’ve done their research—a simple Google search taught them about his hippos, his zoos, his palatial homes and elaborate prison breakouts. Hell, they also wrote an essay about his Robin Hood-like acts for class. They have t-shirts of his mugshot.

Britannica describes Pablo Escobar Gaviria as a “Criminal Mastermind.” You get through the list of riveting fun facts and the oxymoron easily flies you by. It’s an interesting choice of words. They immediately aestheticize, speaking to the phenomenal in a way that elevates the subject above reality. The words are also automatically exonerating—a criminal mastermind deserves a movie! And boy, Pablo has plenty. It’s the kind of term you would use to describe the actors in “Ocean’s Eleven.” It alludes to some elaborately genius, successfully executed plan. It makes Pablo’s reign seem like a Hollywood stunt. Like one hundred and eleven innocent people didn’t violently blow up in the air on Avianca flight 203 after his cartel stuffed it with dynamite.

Something about the description is crude—maybe even a bit insensitive. Maybe Britannica hired one of these seventeen-year-old boys to write it.

Pablo Escobar, Criminal Mastermind. Now, scratch out his name and insert the name of the evil historical figure of your choice. The reader thinks of a certain mustached demon and screams at the page—now you’re being dramatic.

My attempt with that exercise is not at all to compare, but merely to illustrate my point. An Amazon search of Ted Bundy reveals a list of books and movies educating you with the stories of the women he killed; but type in Pablo Escobar’s name and you can purchase pretty posters with his face in all different sizes to hang in your living room.

To Colombians, he was a terrorist. But in the eyes of the rest of the world, he’s a Criminal Mastermind. The question is, why? What sets him apart?

I visited my family in Colombia last summer, and on the final day of our vacation, having saved the best for last, my uncle drove me to La Candelaria, the capital’s historic center. Walking on cobblestone streets, we peered at museums, government buildings, and beautiful colonial structures through the flight of well-fed gray doves. This was one of Bogotá’s main tourist destinations, and as we toured we inevitably stumbled upon a row of slanted souvenir shops.

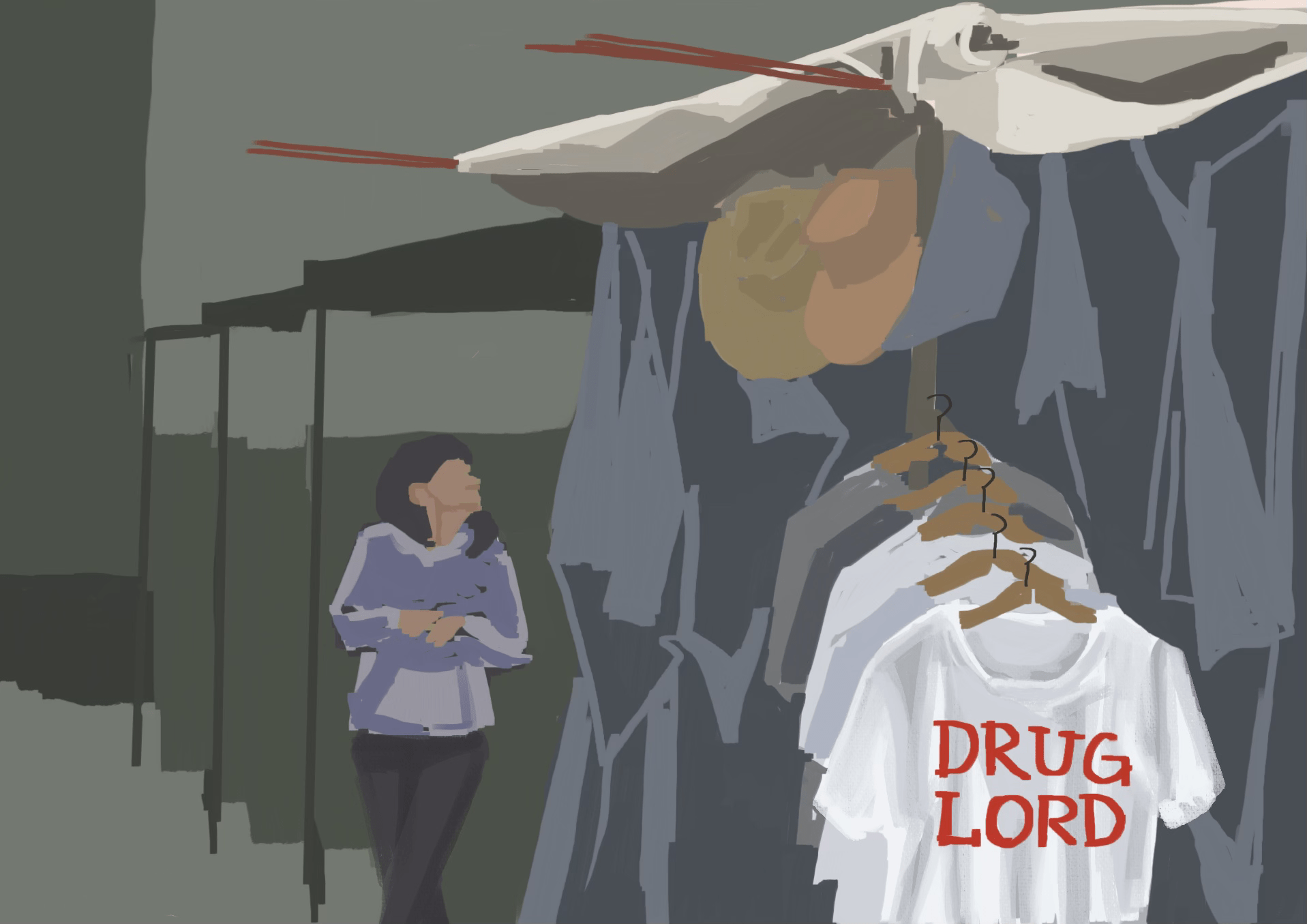

They sold replicas of Fernando Botero’s classic works, black and white postcards of a perched Gabriel Garcia Marquez, intricately beaded native jewelry, and an infinite array of yellow, blue, and red—if the tourists were going to learn anything during their stay in our tropical paradise, it was the colors of our flag. Alongside this, crucified on the wall with pushpins and cables and the slightly bothersome vinegary smell of formaldehyde, were hats, t-shirts, posters, flags, and underwear. They were all pressed with the glinting mugshot grin of world celebrity, superstar, synonym of all things power and luxury—his shirt glowed brighter than the White House in front of which he infamously stood. To some tourists in the store, this was the only real recognizable figure. They flocked—they’d been searching for Pablo Escobar’s delicious image since they stepped foot on Colombian soil.

The sight struck me. The day before, we had visited one of the most popular malls in the city. As we neared the ramp which led down to the subterranean parking lot beneath the mall, several men in dark green uniforms, rifles slung across their chests, signaled for us to stop. When our car approached, my uncle knowingly suffocated the break and they lifted the hood of our car.

“They’re checking for bombs,” he said.

Garnishing the mall’s perimeter were buzzing restaurants, neat office buildings, and drumming nightclubs. The damage that could be inflicted by a car bomb would be catastrophic—it also wouldn’t be the first crater drilled into Colombia’s scarred history. Amidst its abundant biodiversity, beautiful landmarks, and delicious food, war raged in the eighties and nineties as terrorist groups fought over the country’s resources—king among these, the Medellin Cartel led by Escobar.

Sadly, there’s still an undeniable nexus between that name and The Republic of Colombia, and the continued association of criminals like Pablo and our nation can be likened to phantom pain: The limbs that were rotted by drug trafficking were crudely amputated—as if by a saw and a biting cloth—with Escobar’s death in the nineties. But the stumps are suffused with electric shocks as Colombia’s reputation continues to be inextricably linked to its victimization, perpetuated by pop culture and the ignorance that continuously romanticizes such drug lords. The wealth and power swirled into drug production create an intoxicating aroma that, upon inhalation, dizzies you into blindness—one need not ingest, snort, nor inject to feel tickled: the stories are drugs themselves. Even the name of their moguls, the idolized Drug Lord, is allusive to the divine. Terrorists become glamourized beneath the purple haze.

Odds are, those who wear Pablo Escobar’s face have no idea that in December 1989, his cartel set off a car bomb in front of the country’s Department of Security (DAS), killing over sixty people and injuring almost six hundred. Escobar’s cartel murdered countless politicians, presidential candidates, judges, magistrates, and journalists, and offered two and a half million pesos (a monumentally larger sum than the average minimum wage of the time) for each policeman that was murdered. One hundred bombs were set off by the Medellin Cartel just between September and December of 1989, destroying public spaces from stores, to schools, and banks, inflicting a reign of terror that left people fearing for their lives every time they stepped outside. Escobar’s reign left an estimated fifteen thousand people dead, and inflicted social and political temblors that still shake our nation.

That Pablo’s image is sold in the very country he terrorized is not due to a lack of conscience or ignorance. Most Colombians are aware of his crimes in the same way Americans are aware of 9/11. The catering to tourist demands is merely the recognition of a fact—drugs and their champions are sexy.

Pablo’s face sells. And the uninformed tourist, by nature, scoops it up and feeds it to his seventeen-year-old gangster loving son, a poster to crucify the martyr to his bedroom wall.

Art by Chas Brown

Leave a Reply