When the sodium lamps evaporate their tired stock,

I wonder if walking home at night in the rain will still be such

an ageless pleasure, a simple joy to watch you stagger

up cement sidewalks, ringed in a corona of rusted lumen,

a delight to watch it all hang in the balance, illuminated

by an orange light, a muted star, an oozing palette, and

you guiding the night’s ancient brush strokes. You

guiding us back to your place, looking back at me, and me

wandering around the river of sticks on the sidewalk. It

rained, and the air yawned in breathy petrichor.

It rained, and the glittering street became a drunken

bubble, a sacred river, a frozen lake upon which we

slipped when we crossed to go into your crooked building.

I watched the world dwindle down to a stretched out light,

a phantom glimmer on the window pane in the doorway.

I heard the world dwindle down to a hush, as the door swung

shut, and I thought of a TV muting, a friend up-and-dying, a lover

falling flat by gravity’s suicidal supplication,

of what a safety it was to be brought in through your threshold,

a privilege to not have to find my own way home tonight,

in the muted breeze, the trickling rain, under the light of the old

sodium lamps—the ones that flicker from age—and fumble

a keyhole in barter for warmth. You ask me if I’m okay because

I’ve been thinking all these things, and my face has gone hopelessly

blank, my eyes have gone tracing a crack in the tiles on the wall,

following it upwards until it sprawls, branching in driftless

fecundity. And I have both too many and

too few cracks to trace. But I nod in response, an uncertain

affirmation, a particular restitution of something lost in my gestures

towards the metaphysical. But I’m back now. In this entryway—

your entryway—my eyes locked with yours in a brief moment

of respite (from the river, the lake, the cracks, the fear

of falling). Respite enough to walk the stairs up to your

room. And the specific scent I’ve begun to associate with

sliding doors, and narrow decks, and other small features of my

birthright (my home, that is). And you left your window

open. We always go back to your place.

I always go back to the red chair, the first time I sat in it. You

were wearing a white t-shirt, and I was wearing a cable-knit sweater

that matched the chair. I think we laughed about that.

I always go back to the chair I sat in on that one night…

And now the anchor of time’s heavy hand has made that chair

an antique. If this world saw time in our senseless notions:

endless, reversible, mendable, I might not fear something like the

evaporation of the sodium in the lamps. Because at least I could go back

and undo it (or resupply them, if that would do the trick). I wouldn’t

trace the infinitude of cracks on the wall, or search for the art

of night’s blackened, star spangled street paint. I wouldn’t

yearn to remember these moments: a night as normal as this one.

And the world we are in obeys our laws of elasticity, and time

on scales of reversible tabletops and spinning tops and hands

clutched on counter tops, and moments suspended in humid air

and…that trip we took down to Philadelphia in the snowstorm.

If time could be frozen there, I would watch the lamps snuff out and not

blink an eye. But the minute hand on the clock always overlaps

the hour. Time pressing forward in some predestined chase,

and we watch the moon blink out, the doors swing shut, the

people vagabonding tirelessly on the streets outside your window.

So I wrap these memories, coil them around my finger,

in the curls of my hair, in the sulcus of some rememory.

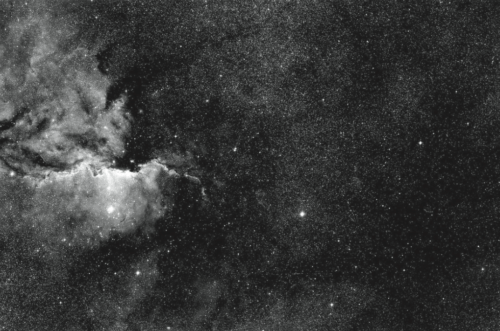

And I map the curl of your grin to a constellation watching

our stagger back to your place. Because something about the stars

and the cloudless night feels at least somewhat

permanent

Leave a Reply