A rainbow shines over a series of excavated ancient mosaics that line the walls of Princeton’s headquarters in Antakya, ca. 1938. Photograph courtesy of Visual Resources Collection, Department of Art and Archaeology, Princeton University.

Nestled between the rugged Mount Silpius and the Orontes river at the northeast corner of the Mediterranean, Antakya in the 1930s was a lively, cosmopolitan town lying above thousands of years of history. One of the oldest continuously-occupied cities in the West, it passed through many hands: Greek, Roman, Persian, Byzantine, Arab, Armenian, Seljuk, Crusader, and finally Ottoman. In 1925, Antakya found itself grasped by the French as part of their mandate in Syria. At the time, Turks, Syrians, Armenians, Jews, and other minority groups clustered in tight-knit neighborhoods, bartering at markets that lined the main street and stretched for miles. On the surrounding plains, farmers cultivated wheat fields and olive orchards.

When Princeton art historian professor Charles Morey began dreaming of a grand excavation sponsored by Princeton in the 1920s, he picked Antakya – or Antioch, as English speakers called it at the time – as a prime location. Once the third largest city in ancient Rome, and continuously occupied since, it showed immense archaeological promise. Sources from antiquity hinted at grand palaces and majestic forums that lay beneath the town. Morey wanted in.

The geopolitical situation made Antakya’s location even more enticing. France had recently brought Antakya under its control, absorbed as part of the country’s Mandate in Syria that followed the cataclysmic breakup of the Ottoman Empire. Negotiating with a young and bold Türkiye, France set up a “special administrative regime” in Antakya and its surroundings known as the Sanjak of Alexandretta, which granted special recognition toward its Turkish minority. The terms of France’s mandate were vague, but solid enough to relax the Sanjak’s rules on archaeological digs.

The Ottoman Empire, which had ruled Antakya since 1516, restricted foreign excavators from entering their territory and excavating objects to ship back to Europe or the United States. France took the opposite approach, according to Alan Stahl, Curator of Numismatics at Princeton. Dr. Stahl researches the coin collection from Antakya and teaches a class on the expedition.

France set up the Syrian Antiquities Service in a way that invited Western archaeologists to extract artifacts to colonial metropoles. The Service gave them extensive authority to dig and established a policy of partage, whereby the Mandate would allow excavators to take home as much as half of the spoils of an archaeology dig, according to archival records.

Morey wanted to dig at Antakya to explore what he saw as a history of decline, from the glorified art of antiquity to what he saw as its inferior Byzantine and medieval counterparts. “To some extent that was sort of progressive of him, because most people just looked at the ancient art and didn’t even wonder what the process was whereby it changed,” said Dr. Stahl.

To make the excavation a reality, Morey formed a committee of funders. Calling in Princeton connections, he brought on board the Worcester and Baltimore museums of art, among others. The Louvre even pitched in, with certain conditions. Negotiations took time because the Great Depression had made money tight. The sponsoring museums demanded a significant “cut” of the artifacts excavated in exchange for their backing. As a result, the economic conditions that supported Morey’s academic question were also set up to extract ancient artifacts to Western museums.

Eventually, the Committee found their team of archaeologists. Among them were Clarence Fisher, a freelancing, impatient archaeologist; Princeton professor George Elderkin, a wizened scholar but inexperienced archaeologist; and young William Campbell, Princeton graduate and a new faculty member at Wellesley College. A cast of supporting characters cycled in and out (including Donald Wilber, a young architecture student who later orchestrated the CIA’s overthrow of the Iranian Prime Minister). In 1932, they began their work.

After arriving in Antakya, the team set up shop in a comfortable house, hired a few house servants, and began to send biweekly reports back to Morey, who oversaw the excavation for the subsequent seven years from his desk in the now-demolished McCormack Hall. Led by Fisher and Elderkin, they then began to hunt for potential dig sites.

They quickly ran into difficulties, unprepared for the geographical features present in reality but absent from their outdated maps, for the sheer scale of the dig, and for the land acquisition process.

“They’re in their fedoras and in their beautifully tailored suits, prepping up for the day,” said Andrea De Giorgi, professor of Classics at Florida State University and co-author of a book on Antioch’s history.

“They get to the site, [and] have no idea what things are like. They have no local stakeholders, they don’t have interlocutors [or] local folks whom they trust. None of them speak a word of Turkish, let alone Syrian [Arabic].”

Having obtained permission from the French-operated Antiquities Service, Elderkin and Fisher began to acquire land on which to dig, purchasing or leasing it from local landowners. Most of the time, the team paid a sum for each plot, and compensated for any damaged property, including for any olive trees that had to be dug up. In some cases, they even accommodated wishes from landowners to spare trees from destruction. With these accommodations, the team was mostly able to get the land they wanted with ease.

However, records written by Fisher and Elderkin show that they made little effort to form close relationships with the local Antakyan community, at least in the beginning. That lack of effort occasionally complicated purchase negotiations. Although Elderkin managed to purchase land amicably much of the time, when talks broke down, he sometimes threatened to use a provision in the mandate’s Rules on Antiquities that allowed him to expropriate their land outright.

For instance, in the early days of the expedition, Elderkin threatened expropriation on landowners who in his view had reneged on their lease agreements. He did not treat their alleged about-face kindly. “Believe me these Turkish proprietors are the most slippery eels in and about the Orontes. Two gave verbal consent and within 24 hours had faced completely about,” he wrote in one case in April 1932. “The land of both will probably be expropriated before the end of the campaign.”

Upon a brief examination of archival material, it seems that are at least two other instances where Elderkin or another senior Princeton excavator threatened to expropriate a landowner’s property for the dig – even as late as 1937. Even if they did not have to follow through, this threat made those landowners give way.

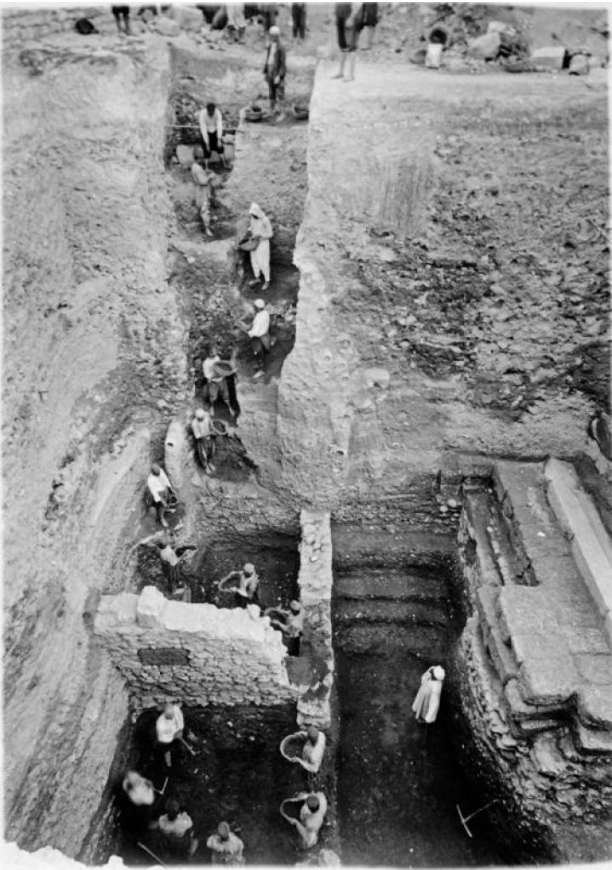

Once it had acquired enough land, Princeton’s team worked out a system for the dig. Relying on an ethnically-stratified division of labor, Elderkin and Fisher tried to locate classical monuments: a large Roman forum detailed in a sixth-century report, some temples, and the grand Palace of Diocletian. They first began by digging holes as deep as 10 meters along Antakya’s bustling central road, hoping to locate the old Roman road that could serve as a reference point to find other notable buildings. No luck.

Hired workers carry baskets of earth up a large trench. An Egyptian foreman, bottom right, watches over the progress. Excavators hoped they could locate an ancient Roman road which could serve as a reference point to locate classical structures nearby. Photograph courtesy of Visual Resources Collection, Department of Art and Archaeology, Princeton University.

Instead, most of what the team found in their early days was baths. But in those baths lay mosaics. It was these mosaics that would redeem the trip in the eyes of the archaeologists – and their funders.

Many of the museums that funded Antakya’s excavation were brought in through what Dr. Stahl calls the “old boys network.” But they stayed because they thought the project could furnish their collections with valuable artifacts, boosting their profits and prestige. Still recovering from the Great Depression, they were especially anxious to ensure that the excavation made them a profit, or at least would not lose them anything. “There’s that veneer of scholarly involvement because the actors here are scholars on the highest statue,” Dr. De Giorgi said. “But at the end of the day, this is an enterprise that… had to reckon with sponsoring institutions that would not cut any slack.”

After uncovering mosaics depicting mythical hunts or tableaus at the bathhouses, Princeton’s team started to search for more. They quickly realized that the mosaics would excite their sponsoring museums and justify the cost of their excavation. By now, Campbell was in charge of the dig, and he was aided by a surging phenomenon in 1935: local landowners started to come to him to report mosaics in their backyards and to see if he wanted to dig them up, likely because they realized they could make some extra money off of the resulting land lease. With this shift, the whole focus of the project changed. “By ’35, easily, if not a little bit earlier, we are just hunting for mosaics,” said Asa Eger, history professor at UNC Greensboro and a researcher of Antakya. “What begins in all fairness like a great project soon does become a museum hunting [and] acquisition trip.”

The project thus participated in a broader framework of colonial resource extraction prevalent at the time, with the resources in this case being antiquities. “Part of the concession made is: you give us money, and we’ll give you some mosaic floors,” Dr. Eger said.

In the evolution of the project’s goals, archaeological rigor became less of a priority. Scrambling to dig out and hoist up dozens of mosaics each season, Campbell’s team paid less attention to the material contexts of those mosaics’ surroundings, surroundings which could have shed more light on Morey’s original research question of artistic evolution.

“What are these mosaics? What do they represent? Why are they here?” Dr. De Giorgi wondered. “Why the selection of that myth, that story?

“Your opinion is as good as mine.”

A group of workers, overseen by an Egyptian foreman, hoist up a mosaic to rest on the wall of the expedition’s compound. Syrians and Turks, men and children, worked on the site together. Ca. 1938. Photograph courtesy of Visual Resources Collection, Department of Art and Archaeology, Princeton University.

The excavation concluded amid calamitous conflict. By 1939, Turkish nationalism was growing, a world war was brewing, and Campbell’s team was nervous. Türkiye eyed the Sanjak of Alexandretta and its large Turkish population, beginning to stake a claim over the region. After the Sanjak of Alexandretta won independence from what it saw as the illegitimate French mandate in 1938, the region prepared for a referendum on whether it should join Türkiye. Turkish politicians stoked nationalist sentiments among the Turkish population in Antakya to new heights, bussing in propagandists to rile up the community and passing laws to encourage more Turks to move to the region to skew the vote. That June, the referendum passed, and the region officially joined Türkiye.

Conflict quickly broke out between nationalist Turks and Syrians. “In the end, there was street fighting,” Dr. Stahl said. “That was pretty bloody street fighting.”

Princeton’s team was caught in the middle of this struggle. Initially responding with curiosity and mild interest (“‘oh, there’s a protest in the streets. How cute,’” as Dr. Eger puts it), they soon became fearful. Their reports express horror at fights between Syrians and Turks in their excavation team. Eventually, the situation became untenable.

“The Americans are terrified,” Dr. De Giorgi said. “At some point, they had to basically pack their things and go.”

As the foreigners on the team Campbell raced to box all the mosaics and artifacts left over and ship them to the safety of the American consulate in Beirut. With haste, he closed down the operation for good in September 1939 and raced back to America by boat – Adib Ishak, the excavation’s secretary, stayed behind. With Campbell’s escape, the Antakya excavation came to a close.

The 300 excavated mosaics’ journeys did not end with the excavation. Half went to the local museum in Antakya. Those that left the country as part of Princeton’s partage agreement ended up in the collections of the Louvre, the Baltimore Museum of Art, the Worcester Art Museum, and Princeton. These institutions proudly display their most dazzling finds.

For decades, Princeton maintained the largest collection of the less grand mosaics and over 12,000 smaller items. The university put a few of the more impressive mosaics on display inside the old Art Museum. Dr. Stahl recalls in an email that when he began his job at Princeton in 2004, the university displayed them in more creative locations, too: “Some of the Antioch mosaics were hanging outside, on the back of the Art Museum, exposed to the elements!”

(Eventually, the mosaics were moved inside.)

Today, the only accessible mosaics can be found rather unceremoniously set into the walls of Firestone Library and the Architecture Library.

Aside from a few feature pieces, though, most of the collection was forgotten soon after 1939 – especially the smaller artifacts. Many gathered dust. When Dr. Eger started to rummage through the collection, he unsealed boxes to find artifacts still surrounded by the original packing straw that protected them on their transatlantic voyages nearly a century ago. “We even have some small cigarette boxes that have fragment[s],” said Carolyn Laferrière, Assistant Curator of Ancient Mediterranean Art at the Princeton University Art Museum.

They were, according to Julia Gearhart, Director of the Art and Archaeology Department’s Visual Resources Collection, “tucked away in different closets” for years without attracting much attention.

That is beginning to change. Princeton conducted an inventory of the entire collection in 2015. Dr. Eger, Dr. De Giorgi, and Dr. Stahl have all started academic projects based on the dig’s extensive records. When the Art Museum opens in 2025, Dr. Laferrière will prominently display some of Princeton’s mosaics in her exhibition.

The more attention turns toward Antioch, the more questions emerge, especially in the context of today’s calls for repatriation of ancient artifacts. Princeton’s excavators worked in a fraught political era during which multiple nations claimed possession over Antakya and its ancient artifacts. The French may have given Princeton the legal right to excavate and extract much of the collection away from its place of origin – a right extensively proven by the expedition’s records. But did France really have the authority to do so, given its murky jurisdictional and moral claim to the region? Today, does that affect who should rightfully possess Princeton’s artifacts? Can anyone claim to “rightfully” possess them? And if not, where do these mosaics belong?

William Campbell, who succeeded Elderkin and Fisher as the excavation’s field director, sits with his notebook on ruins in the outskirts of Antakya, ca. 1938. Photograph courtesy of Visual Resources Collection, Department of Art and Archaeology, Princeton University.

Leave a Reply