The Glee Club is nothing like the happy-clappy high school show-choirs popularized by the adolescent TV show, featuring the all-too-zealous Rachel Berry and her strangely attractive posse of high school drama kids. The Glee Club is self-proclaimed to be the “oldest and most prestigious choir” at Princeton, founded back in 1874, almost a century before women were first admitted here. Instead of peppy show tunes or soulful ballads, the Glee Club’s repertoire is largely taken from the rich Western choral tradition of composers like Bach and Brahms. Perhaps the word ‘glee’ in the name is entirely misleading — words that come to mind are instead ‘professional’, ‘esteemed’, and most of all, ‘serious’.

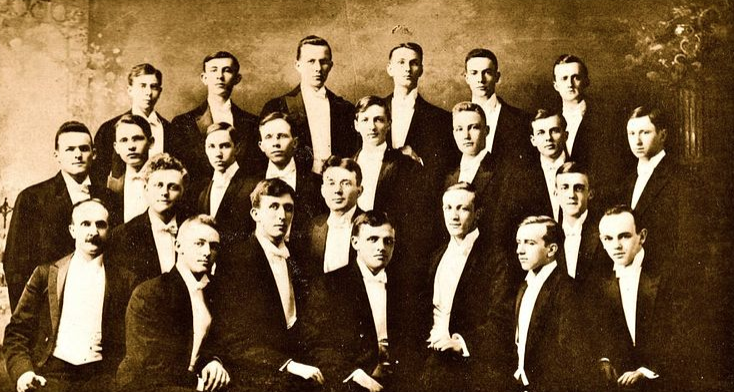

Up until last year, Glee’s performance uniform was very traditional – men wore white tie tuxes (conventionally thought of as the most formal mode of masculine dress) with a slither of orange across their chest, and women wore long black gowns with an elegant string of pearls around their neck. The choir displayed a refined façade which seemed to complement the similarly traditional repertoire and technique it showed off. That is now an outdated image.

We should be thankful that the Glee Club has taken strides towards progressive change. They let women in the choir not long after they were admitted to the university, and nowadays the choir is pretty evenly split in terms of gender. Within Glee, the director has always been open-minded and willing to accommodate every members’ needs. In the past, if any member felt uncomfortable wearing the performance dress, they were given the liberty to wear their own formal attire. One such member is Eli, who identifies as non-binary and likes to experiment with how their style relates to their sexuality. While the Glee Club still adopted their old uniform, Eli said “I felt like I couldn’t be myself,” and they would wear a form of formal concert attire that involved black, covering clothes. Some other members who thought that the uniform may have been too constraining wore black turtlenecks and trousers for greater comfort. This resulted in a lack of uniformity, which may have become an issue among the topmost ranks of the officer corps. A referendum to remove the traditional performance dress was brought up several times by the director of the Glee Club in officer meetings, but not until recently did it take shape. The choir voted and passed the referendum, completely changing the face of the choir, quite literally.

The Glee Club would now wear ‘concert black’, and a second vote shortly after that dictated that there would be a uniform change to the new performance dress. The main arguments put forth in favor of the change were the following: 1) there would be greater inclusivity and freedom of exploration with the removal of the gender-binary element of the old uniform; 2) professional contemporary ensembles like Tenebrae (of which our director is a member) dress in “concert” black; 3) the cost of the traditional concert dress is too high. As convincing as these arguments sound conceptually, I do not think they play out in reality.

To help members understand what “concert black” entailed, the officer corps issued a list of prescriptive guidelines. Essentially, the pieces of clothing had to cover all parts of your body from the neck down to your toes, qualified however with the vague instruction to be “unadorned, classy and elegant.” This was not a bad attempt to keep uniformity outside of the confines of the traditional gender-binary performance dress. Yet something struck me — I noticed that the language of the guidelines seemed to enforce the gender-binary rather than eliminate it. Items conventionally considered to be masculine like ‘slacks’, ‘button-down’, ‘suit’ and ‘tuxedo’ are grouped together, while things like ‘floor-length dress’, ‘jumpsuit’ and ‘skirt’ were on the same line, suggesting that the items within these groupings were either interchangeable or complementary to each other. This played out in performance — everyone who, to my knowledge, identified as “male” wore pants with either a turtleneck or a shirt, while everyone who identified as ‘female’ either wore a dress with leggings, or a suit that was clearly more form-fitting and flattering with more exaggerated lapels. It seems that the issue is not the traditional forms of performance dress, but rather that clothing itself inherently asserts a gender-binary. One of the biggest reasons for this is commercial — it is easy and savvy for brands to categorize clothing by gender because the reality at the moment is that there is little overlap in what society expects “men” and “women” to wear. It would seem that the conversion to ‘concert black’ did not encourage more exploration of style and that the gender-binary was enforced rather than dissolved.

The optimism with which some members of Glee strive towards the technical precision and dynamism of professional choirs such as Tenebrae and The Sixteen is extremely admirable. When I listened to the former’s recording of Hubert Parry’s Faire Is the Heaven, I was blown away by their silky blend, their exciting stylistic flourishes and the meticulous precision of their intonation. Should we really compare ourselves to a Grammy-winning ensemble? When we try too hard to mirror the prowess of these choirs, we lose all sense of self, and the choir becomes stuck in this confused limbo. We ought to have role models, but we should not try to replicate exactly what they do. To be clear, I am not criticizing Glee Club’s musical quality or professionalism. On occasion when I sing with the Glee Club I get chills down my spine in the most sublime of moments in the music. But we should not think ourselves to be something we are not. We are a historic university choir made up of more than seventy students, many of whose primary goals in life lie outside of singing; they are a contemporary ensemble of twenty professional singers who have bravely dedicated their careers to this artistic pursuit. While I do think that the members’ idolization of choirs like Tenebrae is valid and well-deserved, the comparison between our choir and theirs is invalid and unfounded.

It is very important to consider the price argument put forth in favor of the uniform change because the number of times a performance uniform is worn often does not compensate for its hefty sum. It may indeed be true that the cost of a black shirt, black pants, and a black blazer are lower than that of Glee’s tux, which came up to around $175 last year. Many members were frustrated last year because they had to pay a rather exorbitant amount for an outfit that they were only going to wear around a dozen times in their whole life. But this referendum felt like salt to an open wound — it was tough that we had to pay a hefty sum for this event-specific uniform, but it made matters worse that we only got to wear this costly garb for a quarter of the expected time and that we were now forced to purchase new pieces of clothing in its place. Now, the tux sits forlornly in a wardrobe, never to be worn again. Unfortunately, the economic argument was really only marketed for the freshmen without much consideration for the members who were coerced into buying the uniform in past years.

Perhaps Princeton’s Glee Club has situated itself in a good place as a pioneer of progressiveness in the realm of Glee Clubs. Harvard’s is still all-male; Yale’s still adopts the aforementioned traditional performance dress. We also removed in a way a uniform that very much reinforced a classist societal structure. Yet in the hodge-podge of black, unadorned, classy, and elegant clothes, one has to wonder if the stripping of the white shirts, the white bowties, the white waistcoats and the white strings of pearls has really achieved anything.

Leave a Reply