This review started as an obligation. It was the least I could do, really, to thank my friend and congratulate them on their poetic debut. Then, when I finally opened my personal copy of the book, sent to my home address after I’d emailed a certain publisher by the name of Will Ballard with a request (on behalf of the Nassau Weekly, naturally), and saw the note of gratitude inscribed in blue marker on the inside cover, I knew there was no way out of the task at hand. Admittedly, all I had wanted was a free copy of the bound poems to peruse at will (It’s not everyday, afterall, you recognise the familiar name of someone you once sampled Jaegerbombs and Guinesses with printed on the title page. Items such as these, I figure, are necessary keepsakes…). Seeing the chipper ‘Thanks!’ though, inevitably meant I’d now have to determine the best way to actually talk about the poetry, too.

A whole collection of poems, I marveled with a shudder as I flipped through its pages. I thought back to the hours I’d spent last May and June, repeatedly counting out –clapping, even!– sonnet syllables in frustration (such are the exercises any student eager to study creative writing is prey to, no matter whether their interests lie firmly in the department of prose or not). I’d share these tedious sonnets with my tutor, then scrunch my nose in suspicion whenever she’d thoughtfully announce that I had the real makings of a poet. The potential. Noam, I reckon, has a great deal more than what our shared tutor diagnosed in me as ‘potential.’

I suspected this prior to getting my hands on Officeparks. I’ve read some of Noam’s poetry before –even attempted to offer careful editorial advice at Noam’s bequest. I came to this specific collection a bit late, however, though I’d heard of its making since mid-January. I must have heard it once or twice. “I’m publishing a book of poems,” Noam casually declared to their audience one day –and another (perhaps, it was over lunch…over dinner, in the dining hall, where some variant of potatoes and other quintessentially-English fare was certainly on the menu). And although I could not say when precisely I grew certain of this commendable endeavor, I do know Noam was the closest I had to a living, breathing, post-post-modern poet before me at the time. Someone who was presently generating. Creating.

In their spare moments during our time as visiting students at St. Edmund Hall, I can envision Noam walking around –a bit over here and a bit further over there– until they’d find themselves at the point where the poem had been written before them. Not that Noam was ever an especially avid walker, though I reckon they walked just enough for the poems to find them. I was walking too. And watching.

Noam found the poems, or the poems found Noam, or maybe it was a mutual finding. No matter how exactly it was that the poems came to be, my wonder came from witnessing this creative act –from simply knowing a close peer of mine was putting pen to page. This is not to say I lacked writer friends prior to my encounter with Noam. One such friend, for instance, wrote the Nass’s first non-English drama. Another aptly named a new Dante. A third beautifully described the ‘dog-eat-dog world of the Balkans.’ Most of my writer friends treat this production as something akin to a secret though –a passing hobby or a sheepish indulgence. Perhaps, I take greater pride in their words than they do themselves. Few are so brave as to admit to the profession, especially at this young and tender of an age. For Noam though, this was never the case. For Noam, it was an insistence rather. They were a self-proclaimed writer from the moment I met them, confidently ascribing the title to themselves until I came to truly believe it. Embarrassed is something Noam could never be.

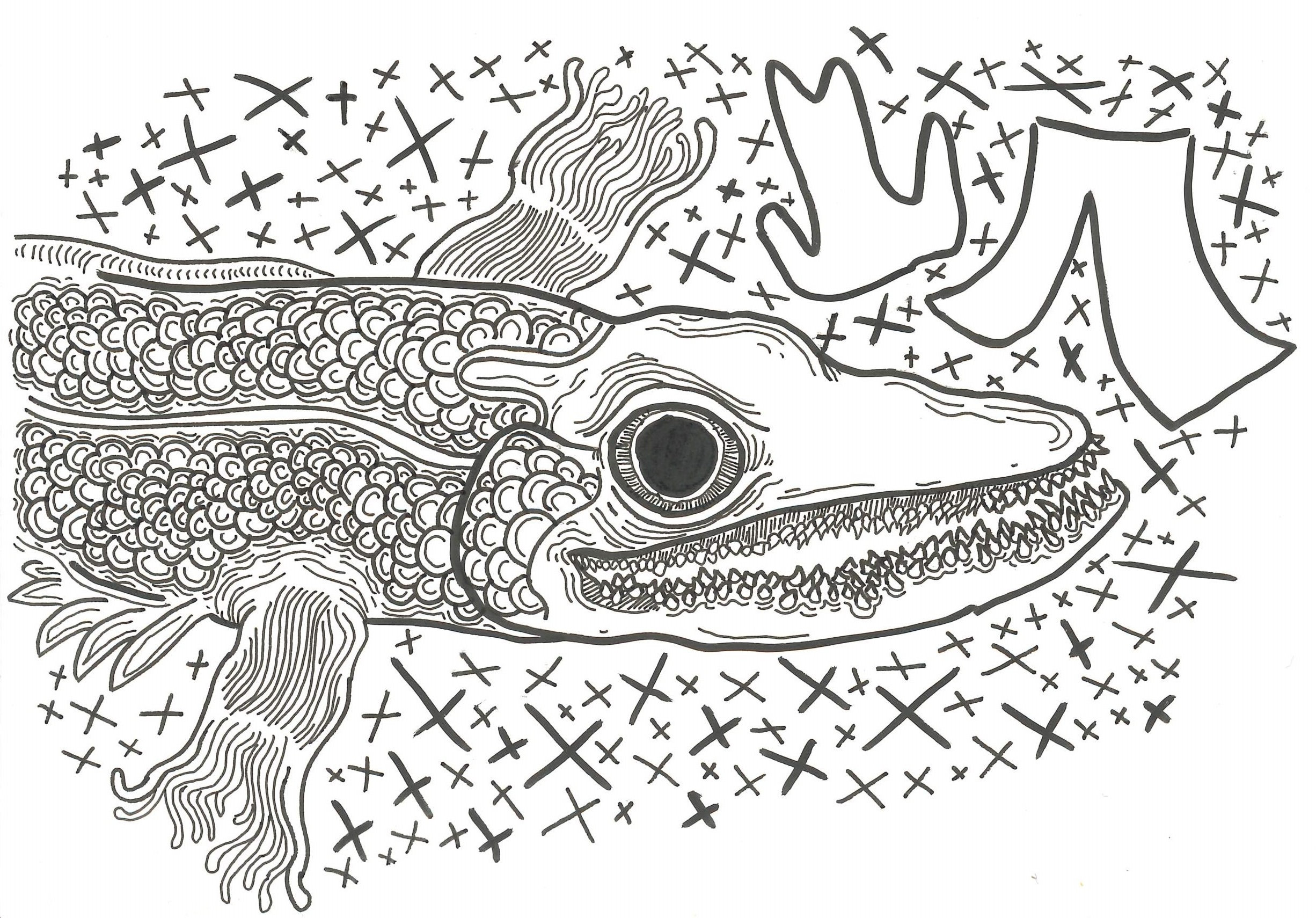

I’ve been thinking about what exactly makes Noam’s poetry different from other contemporary works I’ve encountered. What makes the poems approachable? Less off-putting, and clunky, and ridden with the dreaded clichés that most writers are taught to fear? There are, of course, the illustrations which draw one in. I’m distinctly fond of the alluring fish that appears early on following “Deepsea Lizardfish.” This image, I am sure, I saw come alive before my very eyes one morning during a Gogol lecture. Noam would never take notes, nor would they simply sit through our beloved professor explaining the 1830s surge among many Russian writers for a ‘usable’ national identity and their (arguably futile) quest to identify what Russianess is. Instead, Noam’s pen would be moving, producing pleasant curves and lines in their notebook, which provided for marvelous distraction during that one hour of lecture. Wednesdays. 10:00 am. Whilst my fingers struck the keyboard with a furious clacking in an attempt to transcribe the professor’s every word, Noam pursued the finer arts. The black bled onto the page. I swear I remember it catching the professor’s eye –more than once. I hope Noam sent him a copy.

I recognise, too, the drawing found on page fifty-two –the “Exhale,” as I’ve personally deemed it. Much to my delight, I found it paired with one of my favourite poems from the collection, “Five Snapshots of the Spy.” Noam leaves the reader missing this boy of theories described. It looks as though he’s young…he isn’t in / Our files. I still miss the boy myself, at those parties in Moscow.

This is not to say, certainly, that the only appeal of Officeparks is all the illustrations drawn by Noam themselves (and I concede, too, that such an appeal only highlights my personal bias). Rather, Noam has a knack for conjuring images –of both the quotidian mundane and the viscerally uncomfortable– with the very words they colour their poems with. If anything, Noam knows best how to pick a word that is charmingly fun to say out loud. I’m especially a fan of the à-la-Mayakovsky:

— Mushroomclatter.

Robberstamp.

Coffinrumble.

Vulgartramp. —

One might describe Noam’s poems as noisy. You can hear the images, and this renders the poems in another dimension –that of sound– which gives them life beyond the physical page. Noam is further unafraid of pushing the constraints of form. Although I cannot pretend to understand metre and rhythm as any good poet would (and, here, is why I only have the aforementioned poetic potential but not the skill), I can pick up on visual cues.

The titular “Officeparks” is one such example, where brackets and bold and slashes are introduced to give us the story of David and the fiefdom. Or there is “Barnbuyin,” which nearly screams at you in all its caps-lock power. I do not think I have ever been screamed at by a poem before. Noam is, too, the poet who will unabashedly admit to falling under influence. Page forty-one presents the reader with “The Tumbleweed” inspired by Bryusov, of the Russian Symbolist Movement. I wonder if Noam is not laying Marxism’s seeds in the West as well (when asked whether they’d describe themselves as a Marxist in any sense of the word, they affirmed with a simple “yes”). And then, there are all the musical compositions. Only Noam would think to signal for the steel drum to start –to include a guitar and a bass in their poems (the tempo of the vocals quickens). The poems grow louder.

Noam does not always insist on big, bold letters and the addition of the drum’s beating though. In fact, perhaps I like best what I consider to be the quieter poems in the collection. Take, for instance, the last poem, “The Burning of Windham County Parish, 1960.” Only at the end are the readers at long last introduced to the:

Wanderer of wanders,

Strummer, guitar picker

Oh so dextrous,

Snub-nosed troubadour.

The wannabe poet king whose voice we hear in these lines arrests the reader with their questions, and we’re left wondering in tandem with the speaker. There is a palpable sense of urgency to this final, ten-piece movement. This may very well be due to the fact that God is now a key player, and he seems cruel. This God needs no poet, the speaker reveals. Such a statement comes as quite the blow at the end of a debut poetry collection otherwise filled with much cheek and promise. What to do? Here, it almost feels that Noam concedes –in a Wildean fashion: All art is quite useless.

Noam does not, however, leave their readers stranded. The flowers bloom in Montreal this time of year, the poem concludes. We’re invited to move north with the poet king. And so we beat on.

Just as Noam believes, I’m sure that one day scientists will…uncover that there are certain places that hold poems and jam them into a poet’s head. These poems will be carbon dated and shown to have originated within the poet years, weeks and even hours before the poet received them, before being catapulted to another time, as is their way. It’s my belief that all the poems that the town of Oxford held from January to June of the year two-thousand-and-twenty-five were jammed into Noam’s head –and how glad am I that they were, despite any so-called God’s lack of need for them. When the carbon dating results are finally available, I like to imagine science will prove that some of the poems were received during the time Noam and I spent there together in particular, walking to and from tutorials or fighting over who gets to check out the sole Vonnegut copy from the library. I’m still afraid of poetry, and I don’t know how to talk about it. Like Wilde, I reckon it all is quite useless.

I could tell you about my friend though. They’ve published a book of poems.

Leave a Reply