Do you ever feel like a plastic bag?

A sheriff walks into a party for a noise complaint, without a word or a mask. As he reaches the party’s speaker setup, the music cuts out with a thump.

“What’re you doing? Not here on rape charges? Didn’t really pan out for you did it?” the host sneers: His hands rest on his hips, unable to stay angry knowing his reelection is secured.

…come on let your colors burst! Make ’em go, “Oh, oh, oh”..

The music resumes. The ensuing scuffle over the speakers is the release of an entire campaign of frustration. The mayor, who has long been cordial, can’t bring himself to forgive and forget this latest harassment. So the mayor slaps the sheriff, hard, enough to stun-quiet the man’s sputtering abuse. Seeing the dumb shock on this pest’s face, the mayor slaps again: knocking both glasses and sense into the man whose rumors and incoherent ranting jeopardized the new investments that could save this town. According to the pitch the lobbyists gave him, the solidgoldmagikarp™ data center would enable Eddington (“POP 2,345”) to ‘equitably bridge the digital divide’: so may God help anyone who dare prevent that.

Under the din of Katy Perry, the sheriff stumbles away, defeated but plotting revenge. This moment marks the point of no return in Eddington: where mounting pressure’s violent release spells out a horrible fate for the town at large. In an era defined by period pieces and sequels that escape to the past, Ari Aster’s 2025 film tackles the near present and its third-rail issues with gusto. Oft accused of being insensitive and ‘Too soon!’ Eddington risks commenting before the great Pulitzer Prize-winning book, before any sort of establishment narrative. To make such a swing, to so eagerly return to such a sensitive and largely unprocessed time, almost feels taboo.

At a surface level, it’s no wonder that the Covid, Q-Anon, BLM western stirred up controversy. Initially panned by critics, the film was accused of being mean and navel-gazey; a centrist retelling of the pandemic, too sympathetic to the conservative perspective of its main character. Despite the film’s merciless dissection of protagonist Sheriff Cross, a schadenfreude takedown of insecurity-fueled populism, certain early audiences really reacted poorly to Aster’s teasing of the BLM square centrism that defined the era. To this day, the top-liked comment of Eddington on the popular reviewing website, Letterboxd, goes as follows:

1 out of 5 stars. 8099 likes.

“Grossly irresponsible to make a film that attempts to examine the intensely vitriolic state of American politics amidst the earliest months of COVID and not mention how Trump, or the MAGA-sphere, directly amplified and exacerbated so many of those very issues. But at least we can laugh about the youths caring very loudly about George Floyd’s murder…. I found every part of this uninteresting and, maybe even worse, unintelligent”

Transcending forgettable mediocrity, Eddington was framed as one of the worst films of the decade, for its sins of not directly name-dropping Trump, and criticizing the surreal identity politics of the time. I couldn’t disagree more. As people sat with the movie, certain details kept coming to the forefront: Why did those violent ‘Antifa’ agitators have a private jet? And why were the movie’s first and last shots of the planned and completed data center? Moments like these convince me that Eddington is a gripping political thriller, one that dutifully conveys the mood of Covid with an examination of the cultural artifacts the pandemic left behind.

In fact, as ridiculous as it sounds, I believe Aster’s decision to challenge the politics of the median Letterboxd user cements the work among the first great pandemic art pieces, and as a leftist classic deserving of the Library of Congress. In a recent reflection in the New York Review of Books, “Where Wokeness Went Wrong,” leftist moral philosopher Susan Neiman considers the eccentricities of the time. Disagreeing with the new narrative that wokeness was a force for good that went too far, Neiman highlights instead that “by unwittingly accepting deeply regressive philosophical assumptions [loyalty to an in group, etc], it went in the wrong direction entirely.” Yet, while certainly an evocative claim, the detail that struck me the most was about translation, and how as ‘woke’ proliferated across the world, the term was kept in its original English. I believe the power of Eddington comes from a similar place: the film offers the viewer an almost historical perspective, an opportunity to understand these concepts with the ambivalence they deserve. With its beautiful visual delivery of the time’s tech optimism and political polarization, these qualities are explored not as examples of overzealous progress, but as parts of the time’s completely unique political landscape. Thus, the true significance of performative white allyship or schizophrenic Q-Anon ‘protest art’ is preserved, unabashedly so, so that future generations may catch the 2020 strain of feverish conspiratorial thinking alongside us. This almost anthropological understanding of the time is why Aster avoids coming off as soapbox-y and why many praise the film for ‘presenting the problem’ and not some soon-to-be-dated solution.

To clarify, Eddington is not a movie about ‘wokeness.’ It’s a no-holds-barred study of political opportunism and unwitting pawns, set to the backdrop of the same tech takeover that’s unfolding around us to this day. Like the doll houses of Hereditary, the mass surveillance of Beau is Afraid, and the human sacrifices of Midsommar, Eddington is another entry into Aster’s free-will-rejecting oeuvre. Political opportunists, whether they be tech investment-obsessed mayors, hormonal boys, or even the ‘people serving’ Joe Cross fail to recognize they are both puppet and victim alike — as false flag operations manufacture the necessary consent to usher in a water-guzzling data center.

For Aster to focus on data centers in particular really highlights how he’s operating at a level at least a few trend cycles ahead. More than just a ‘tech building’, data centers hold a unique importance in our ridiculous contemporary existence: they are the beating heart responsible for sustaining everyone’s favorite modern inventions like Bitcoin, chatbots, and mass surveillance systems. More than ever, it seems that the Pandemic’s record-high screentimes and online shopping sales have turned Silicon Valley from a collection of rich CEOs into actual royalty. Demands for energy have gotten so high some are trying to clear the path for the first private nuclear power plants, lobbying and suing their way closer and closer with limitless Covid wealth.

Eddington shows its acute understanding of this new system of power with the decision to name the center “solidgoldmagikarp.” On a literal level, ‘solidgoldmagikarp’ is a reference to a real AI phenomenon called a glitch token: certain mundane phrases that prompt unpredictable or nonsensical behavior from a language model. While this direct reading could certainly signal the false promise of the center, a waste of gentrification that will only usher in the breakdown of decorum, the tackiness of the name feels relevant and sadly familiar. By choosing the name, Aster invites us to imagine the fictional tech mogul who would have done the same. The kind of person who would name a company in such a way as to reference AI, Pokemon, and decadent wealth and still get billions in venture capital. Braggadocious, Tasteless, Nerdy, Aster proves that he understands the perverse nature of the ever-threatened ‘revenge of the nerds’. These figures remain completely off screen, their racketeering represented only by the mercenaries and lobbyists that do their bidding. As we transition from a period of oligarchy to one of tech-oligarchy, Eddington understands that, now, the things that kill us will have ridiculous names like the film’s very own ‘solidgoldmagikarp.’

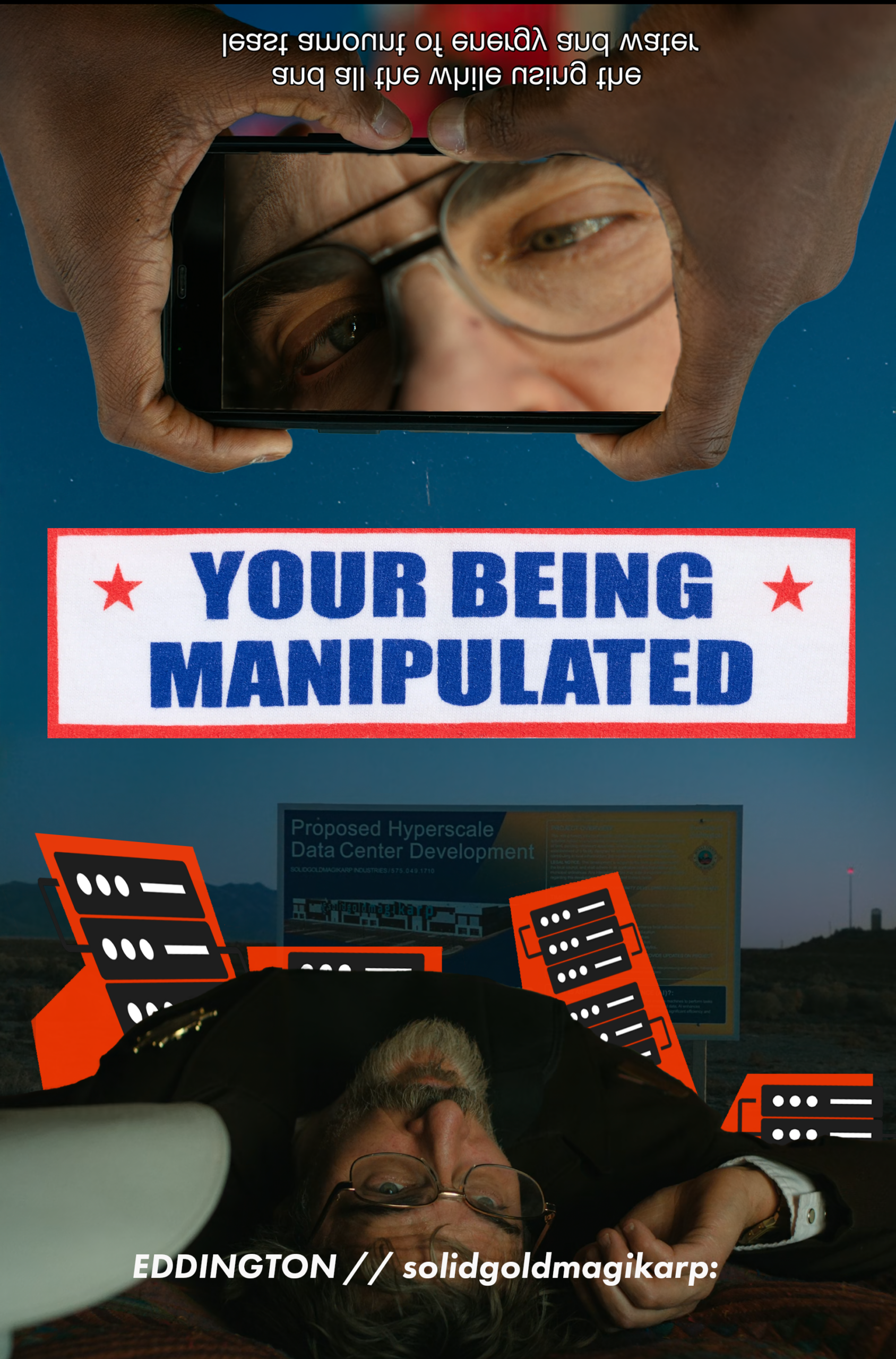

Fig 1. Reflections foreshadow the mysterious symbol on the ‘Antifa’ Private Jet

Often defined by his surreal imagery, Aster has noted on many occasions how he views this film as his foray into realism. Eddington is a film that recognizes that its modern setting necessitates modern actions: that new expressions of the human experience and their novel social consequences must be depicted. In an advancement far more groundbreaking than filming on VistaVision, Eddington has figured out how to beautifully frame a phone as the subject of a composition. The phone is faithfully understood as so much more than just for calling: from the camera to the for-you-page, the wide variety of data the characters generate is used to humanize them in relatably perverse ways. The amount of storytelling extracted from these screens is genuinely something no one else has achieved at this scale. These phones, choreographed to their full potential, do indeed capture pandemic living with an accuracy only possible with a collective wound this fresh. To every critic decrying that the movie was “too soon,” I can’t help but wonder if the film could have maintained any of this historically valuable immersion, if we had all waited a decade; until charged memories faded into something more distant and safer. Aster has repeatedly stated that he wanted Eddington to be both a period piece and a warning for the future, and as much as he’s won me over, I can’t help but wonder if these goals are in tension with one another. To (mis)quote that popular Letterboxd review, it seems that for many, returning to this time in such detail only served to bring them back to that “intensely vitriolic state,” and prevent them from taking part in any reflection on culture.

As much as I hate to admit it, these popular sentiments of anger and confusion do suggest an apparent failure in how many of these themes were communicated. However, while I, too, have my critiques about the film (particularly its structure), it would be a shame if a movie as valuable as this one were written off. I must preface that I went into it slightly spoiled about the role of the data center, and I loved it in a way that everyone I went with did not. This review is intended for the on-the-fence viewer, one who loves political thrillers and can at least stomach leftist discourse. That’s why I believe with just this nudge in the right direction, the film’s messiness can be understood as one of the most harrowingly accurate portrayals of the recent past and present.

Leave a Reply