There’s a bit of swamp water in my mouth.

The boat moves back, and forth. I see them moving the oars, almost in time. There are willows above us, dripping down like little raindrops and making the air green. But I can’t look up, I need to keep my eyes exactly here, straight ahead. My friend, sitting in front of me, has five or six grey hairs. He’s my age. I never noticed that before.

I’m at rowing camp, in Cambridge. If I could look around, I would see perfect British houses along the banks of the River Cam, mud, perfect lawns. Starting to row during my two terms at Oxford was a joke, at first. Then it became slightly more than a joke, an intention. And here I am.

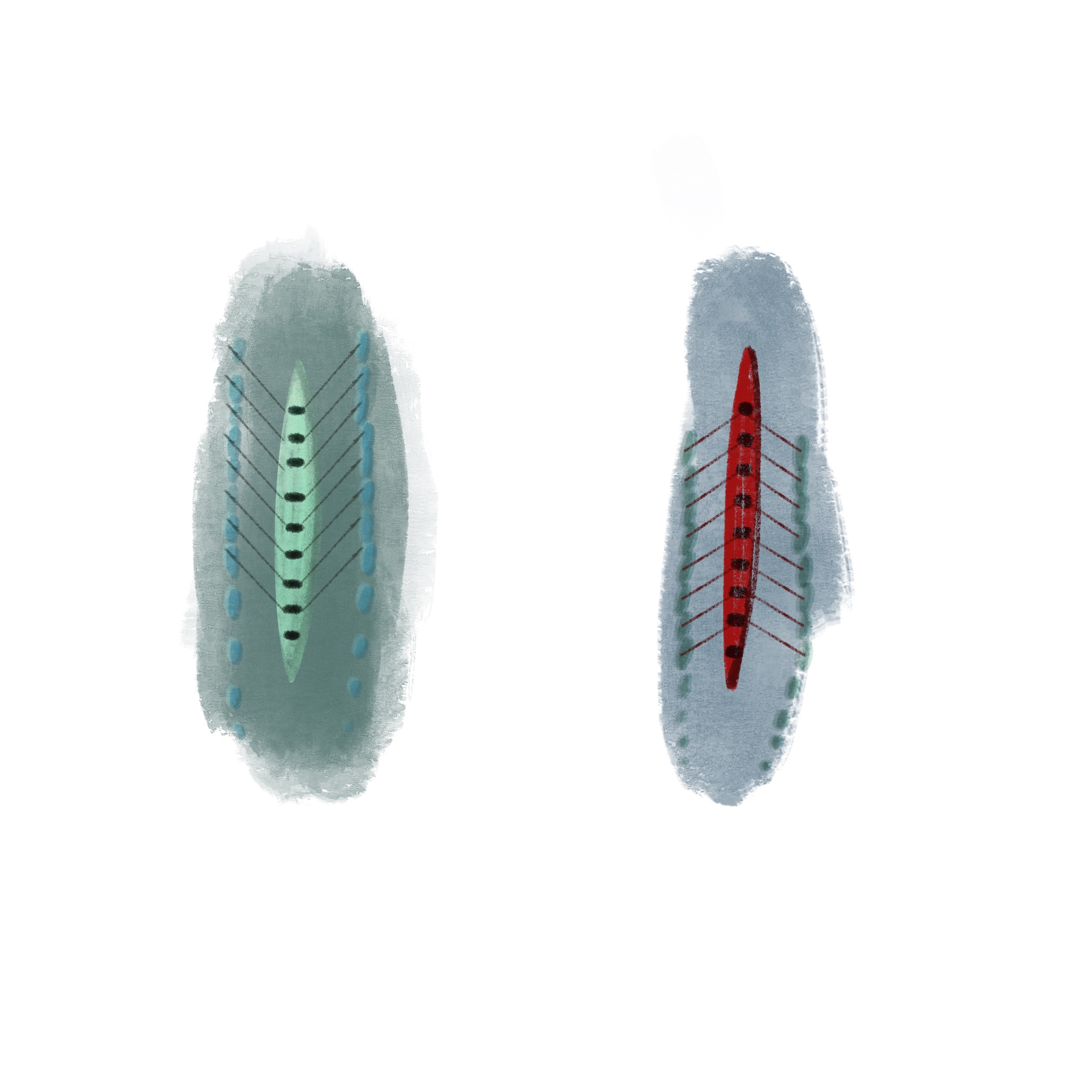

It’s my second time on the water and the wind has cooled down. Enough that I’m not immediately worried that we’ll capsize, not right now at least. Yesterday I caught a crab, messed up a stroke so that my blade got stuck in the water, it spun around and hit me in the chest. The whole boat had to stop. The other group, in the four-person boat, capsized. Right on the bank.

I was upstairs in the boathouse, heard someone calling out, saw all of them fumbling out of the water. Senior members of the club, all rowing at least a year. The coxswain hadn’t gotten into the boat, he was giving them a talk: Bow side. You’ve got to get your oars in the water. Set the boat. See what happens if you don’t.

But I’m drifting. I’m in a boat, there, floating on the River Cam. The water is greenish brown like algae and slime; at one bend it smells like rot. I’m at seat three in an eight-person boat, third from the back. Stern four, the four at the front, are rowing. Any second that could change.

Through the coxbox speaker, a voice, crackling. Not quite a shout. It’s the coxswain. He’s the boat club president at my Oxford college, helped organize the outing to Cambridge. He rows for the Men’s Lightweight Blues, the varsity level. He says: Alright. Looking okay with fours, we’ll try sixes. Three and four on the next, keep your heads in the boat.

I’m holding my blade against the water, tucked in the crook of my outside elbow. Now I take the end of the oar in my right hand, the light green band in my left, careful to push it all the way against the rigging. I know enough to square in the right direction, so the concave side of the blade can push the water instead of flowing past it. I slide forward on the seat, watching the rowers in front of me as carefully as I can from the corner of my eye.

The cox says and, go! I kick off from the footplate and send my blade through the water. A breath. And the boat lurches forward.

That, says our coxswain, is a pretty good example of what not to do. Come on, seat number three. This is a team sport. Let’s keep in time. I spend the next five or six strokes trying to get my blade in time with the others. To match them at the catch—when the blade enters the water—and at the feather, when it turns parallel in the air between strokes. For a second, it feels like I have it. Then I miss. Pretty dramatically. My blade barely skims the water; you can feel it send the boat off course.

Easy there! All at once, everyone takes out their oar, sets it flat above the river. Drop! And you can hear a splashing clatter as they fall. The boat keeps drifting with the flow of water and the wind. So, says the coxswain. I can’t see him through the five rowers in front of me. But I feel his eyes burning through all of them, to land on me.

Number three. We know what happened there. Come on, boys, it’s the second day. Let’s not let it happen again. Stern six at backstops. (All but the last two seats lean back, push as far as they can against the footplates, set the handle against their chest.) Ready… go!

And we’re off again. I try to focus, to hear when the other oars click against the rigging, to see when the rowers in front of me lift their elbows for the catch. On one hand, it’s frustrating. The skill gap is immense, and he must know that I can’t have a feel for even the basics by my second time on the water. He could be a little less curt.

On the other hand, a few minutes ago we were perpendicular. Halfway through spinning, it became clear that not everyone on stroke side knew how to back it down: a backwards row used to turn the boat. Out of control, we panicked, we pitched dangerously to right. Then the cox took over, told us exactly what to do. Without a series of carefully engineered strokes we’d be swimming.

There’s a good stretch when we hit our rhythm, once again, almost in time. The coxswain adds the last couple rowers, so now it’s all eight of us at once. Immediately, the boat starts rocking. Without bow and seat two setting the boat, we’re a lot less stable. All we can do is keep our weight in line and try to keep in time.

We’re around a bend and entering the reach, the broadest and straightest section of the Cam. Even from the corners of my eyes it’s gorgeous. The view opens out. The sky is blue and very wide. Edged on the left and right by trees, more and more distant, sunlit leaves fading almost to mist. Banks of reeds and grass. The world rocks with our boat.

When I’m rowing, I feel like I’m part of something very old. This is how people got around before there were planes and cars and steamships. One time, I took a class on the vikings. This is how they got to Britain, to raid and to settle, eventually bringing English closer to the language we speak today.

But for me, being in a boat is still very new. I grew up in the desert. Our largest body of water is an artificial fishing pond called Tingley Beach; the Rio Grande isn’t the best place for crew practice. Rowing just isn’t something you do.

When the Thames runs through Oxford, they call it the Isis. Almost all the forty-some colleges have a boathouse on its bank. Participation is heavily subsidized and novices—people who have never rowed before—are encouraged to learn.

When I wasn’t in the library, I spent a lot of last term on an ergometer, or rowing machine. The St. Edmund Hall Boat Club is a sweaty place, especially at night: ten or so men huffing and puffing under the glare of harsh white fluorescents; as the warped mirrors start to steam you can hear erg fans whirring and hissing.

Twice a year, the Oxford colleges come together for races where squads try to bump—if not quite ram—the boat in front of them. This year: record rainfall, river flooding. Spring races were cancelled. Almost no one allowed on the water.

So we’re in Cambridge, at boat camp.

Something changes on the Cam. The sky isn’t blue anymore, the wind picks up. Furrowed water, sloshing waves. Ashy clouds. Rain in sheets.

We’re still rowing as eight, but now the river’s heavy. Our timing is off. The wind hits in gusts. If it changes direction we crash right into the bank. If we stop rowing, we’ll be dragged down the Cam.

Keep up the pressure, boys, says the cox. Let’s go. The speaker is loud, it’s hard to hear him over the wind. The boat pitches left, then right; when bow side is down, I can hardly draw my oar out of the water. My hand breaks against the rigging, my squared blade drags before I can drop it back for the catch. Then stroke side is down, my placement’s off. The oar barely skims the river.

The cox keeps shouting: Number three! The blade needs to be in the river to move the boat. But I also hear him call out, Number four! and Number six! I’m jerking my shoulder up at the catch so that my blade dips too far into the water. More of that and it’ll be tugged from my hands. Behind me, I hear the men’s captain. Trust the oar, let it fall. You don’t need to slam it down.

I say thanks, I think, but it gets lost in the wind and I’m onto the next stroke. Even up my timing. Keep myself the same distance from number four’s head as our seats move forward and back. Forward and back. The edge of my attention on the oars ahead of me, they dip into the water. Everything right, for a moment. I realize my oar is sliding into the river now, it’s not crashing.

And we’re around the bend. A picturesque lane, an overgrown bridge. Wind’s gone. Water on my face, from the tumult. All over my forehead and sunglasses. Drips straight down my eye. Onto my lips. My mouth.

(Later that day I’ll be in town, shopping for food. I’ll see a newspaper. Sewage dumped upstream for over four-thousand hours. That night, I will scrub my face with a cheap bar of soap until it’s red.)

The cox calls, easy there! Bow pair, in the last two seats, guide us to a sheltered curve. Well, he says, that was rough. You all panicked. Nobody’s timing was right, and your handles were all over the place. But we didn’t lose any oars, and we didn’t tip the boat. That’s… a success. Slow paddle on the way home. This time, I need technique.

Funny to see the blue sky again, the sun and all the willows and swans in the water, cottages though I’m not allowed to see. Only the rower in front of me, heads in the boat. Forward and back. The feather and the catch. Like something I’ve seen before—a movie, maybe. Or like something I remember.

The breeze is nice. The feeling of the water. And I think to myself, I could get used to this.

On the last day, we’ll take a group photo. I’m barefoot, because the riverbank flooded that morning and when we put the boat down it soaked my shoes. All of us lined up in an V with crossed arms, the coxswain in front. One picture smiling, one serious. Super melodramatic.

Then it’s over. We’re talking about how the outing went and wondering if we’re going to be able to get on the Isis before the summer. One of the captains turns to me and my friend, the only other American. He says, you know, we were picking on you a lot. And it was pretty awful at points. But there has been a lot of progress. At the start you were hopeless. Now, you look like you could be in a bad second boat.

This, I’ll come to realize, was a compliment.

Leave a Reply