Outside – blue, white. The wall of clouds fades upward into the sky itself. Looking over and looking back, my eyes go black. The brightness—the thickness of the wall—sears my vision for a moment. The clouds seem to defy their nature. They seem steady, solid, to me now. My movement seems to win. I am always moving, and the wall stays no matter where I go.

In the spring we talked in the yard. Above—blue, white. Our book club—myself and my godmother—was reading Proust. We read 50 pages each week, ate madeleines, and drank tea. There is loss everywhere, from the very beginning. For a long time… There is a change, something is deprived. Before, Marcel, the narrator, went to bed early. Now, ever later. His mother used to kiss him goodnight. Now, no longer. The thousands of pages begin with a loss. The novel’s creation required a passing out of reality. Above, the wall passes from east to west with the wind.

Under the wall, in the distance, I see Chicago. It was fully cloudy—gray and thick—that day, three years ago. 12 hours before, I had been in Beijing, rushing to pack my things. It felt like we moved past the wall in the sky quicker that day, flying east out of China. I remember the smog that sat above me every day. A different kind of gray. It was easier to tell people in a different language – 我妈死了, my mom had passed away. We cherished the smogless days. They felt as if we had been dropped into another world, supernatural. For once, for just a moment, the wall was gone. On those days we would bike. We’d bike through thousand-year-old alleys. We’d bike fast through traffic, as if a world separated us and the passing cars. We’d drink cheap beer and bike through the night.

“I’m headed home now.” I told my friend this a week ago, before quickly catching my slip. “That was weird,” I said. I was heading back to school from New York, where I had been visiting my family: my sister, my grandma, my uncle, my aunt, my cousin, my other uncle, his girlfriend, my other cousin. We went to a show and went to brunch. We laughed and hugged. My sister and I watched a show from our childhood. We walked through the night. We chatted in cabs, on the train. It rained that night. The windows clouded and rainbows formed around the lights of the Brooklyn Bridge. Drops on the windows slicked down behind the fog. They beaded quickly and fell quicker.

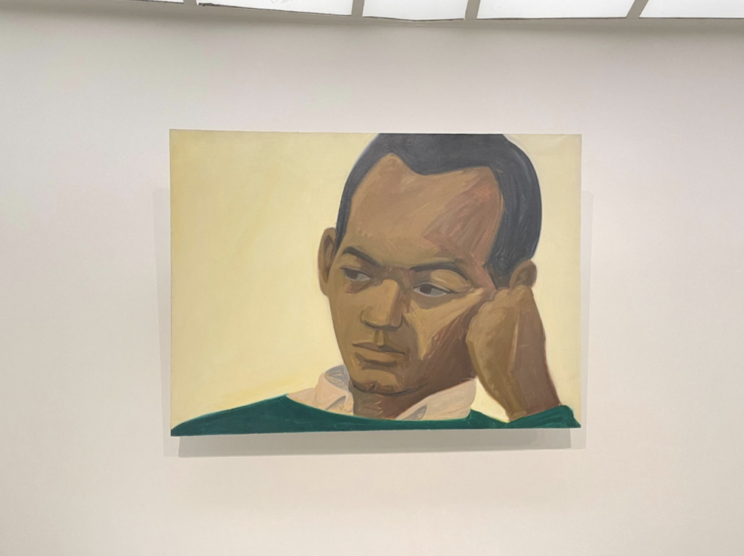

Two weeks before I was in New York visiting my sister and my dad. We saw him across the street on a bench, waiting. Central Park behind him; a pale blue sky above him. The day was deceiving: Cold but completely sunny, cloudless. At the Katz show we walked round and round, up and up. Paintings of Maine, of his wife, of his kid, his friends. Faces made flat, made concerned, made concertedly. One canvas has painted on it a man, one of the artist’s friends, a curator, with his head resting on his clenched fist. With his painted eyes he looks down, seemingly resting. His mind runs. Paint strokes make themselves visible on his forehead, his face a canvas itself. This canvas sits atop another, blank but for a pale yellow. He is out of space, placed somewhere far from home. His internal flux and external calm sends him out of a discernible reality, a world of canvasses, surfaces, pure color. Sun shines down from above. The sky out there leaks in: its glow lights my new friend’s face.

In another sits a son and a friend. The son looks sad and the friend matches his solemnity. Dusk is approaching and the sky behind them paints pictures itself. A yellow stroke through the middle, running down diagonally. Above and below the yellow, swaths of white, clouds. On top, blue sky. It seems as though the sky is trying to express something, its own theory of abstract painting, a theory of abstraction, of chaos and of peace. My dad and I stood in front of it quickly.

More than half a year before, another museum—I remembered taking him to the Musée de Cluny. We wandered through the frigidarium, the Roman thermal baths. The ancient stone cooled us now. Behind the headless men, light divided itself neatly. We stood in silence in this ancient room, looking at the play of the shadow, careless and seemingly bounding from the wall, from its canvas, bringing us in, asking us to dance. Let us dance. Of the tapestries in the Cluny, Rilke wrote, “Is this mourning? Can mourning stand up so straight, can a mourning dress be so mute as this velvet, green-black and faded in some places?” Earlier in the novel, Rilke writes, “Only now did the hundreds and hundreds of details come together inside me to form an image of my dead mother, the image that accompanies me everywhere I go.”

With the light and with these words I danced in this ancient room, in the past. As the light moved with time, as its figures shifted and changed, I changed too. I watched intently as a boy watches the clouds from atop a hill. He looks up with devotion: a dinosaur, a castle, a long and fortified wall. He sees the world in the dance of the clouds. Now, everywhere he wanders he looks up to the sky. In distant lands, Paris, Beijing, and in cities closer to home, New York, Boston, he fixes his gaze up. He travels into the past and creates images of absent things. He makes this landscape in the sky the center of his world. It has to be, so he creates it. When it dissipates, separates with the wind, it only confirms its reality to him. Its dissipation is its existence, and that consoles him.

Leave a Reply