We landed at José Martí International Airport on the fifth day of winter, and the heat was sweltering; the cloying humidity assaulted me as soon as I stepped off the plane. The airport in its entirety is smaller than a New York City block—but I suppose that makes sense if a round trip from Havana to Miami requires a couple years’ worth of savings, as the Cuban man sitting next to my mother during the 45-minute plan ride from Miami to Havana explained. Travel in and out of the country is costly and visas are difficult to obtain, so even the country’s main airport barely needs to accommodate the daily number of flights from LA to San Francisco.

At the time of our trip last December, Americans could not visit Cuba without jumping through several hoops—in order to secure visas, my family needed Treasury Department clearance for what they call a “people-to-people” mission, meaning we were there for cultural rather than economic exchanges. Thankfully we got through customs unscathed and walked through to baggage claim to collect our suitcases—half-filled with our clothes for the week, half-filled with toiletries and other various goods to donate to the communities we’d be visiting while we were there. Spotting our bags was relatively easy considering most items on the conveyor belt were massive, shrink-wrapped cardboard boxes packed with television sets and other electronics not readily available in Cuba. Cuban citizens, I learned, travel to the US primarily to visit emigrated family members and to bring back goods that are scarce or unavailable in Cuba.

When my parents first told me our family would be spending winter break on a mission to Cuba, I was apprehensive. I didn’t know what to expect from a trip to a place I hadn’t heard much positivity about, but my mother insisted that she wanted to see the country “before it changes.” Two weeks before we left, Obama and Raul Castro announced that the US and Cuba would begin thawing relations and reopening embassies. My attitude quickly shifted—I realized I would be experiencing a country that is often described as “stuck in the past,” and with the renewal of diplomatic relations with the US, Cuba would likely soon be catching up to the present.

From the moment we left the airport, the communist spirit of the country was palpable. As we drove to our hotel, Che Guevara’s face stared back at us from countless posters and billboards. Graffitied on a fence in large black letters was the rather dramatic battle-cry “Socialismo o muerte!” The labels on the bottled water on our bus read “no. 1 en Cuba!” as if there were any chance it wouldn’t be (in true Communist fashion, they were the only water bottle company in the country). I looked out the window, watching a world that was ideologically opposite of my own—and probably even more opposite to that of the Texan couple on our mission who were McDonald’s franchisers and self-proclaimed capitalists. The husband wore a polo with the Golden Arches emblazoned on the chest every single day.

I already had so many questions about this peculiar place, and as we pulled up to our five-star, 22-story hotel overlooking the beach, I had even more—namely, what was such a nice hotel doing in such a run-down country? How did Communism work, in practice, and how did tourism fit into that equation?

Our hotel was extravagant but outdated, as many things in Cuba are. The whole country emanates nostalgia; you can sense that it isn’t what it used to be, but that it once was great. Havana used to be a glamorous destination for Hollywood’s elite—myriad celebrities of yesteryear, from Sinatra to Hemingway to Marlene Dietrich, have stayed at the famous Hotel Nacional where we ate our welcome dinner. Now all that’s left are relics of Cuba’s glory days, preserved, it seems, for the enjoyment of tourists. A native Cuban would not have the means to go to the hotels and restaurants we did during our week-long stay, as our tour guide Jorge explained.

I internalized this on New Year’s Eve, when our tour group attended a lavish banquet set up in a town square in Old Havana, in front of an intricately carved Cathedral façade. While waiting to show our tickets to get in, the first thing I noticed was the crowd—there were no Cubans around us, only tourists and expats. I asked one of our mission leaders about this and she confirmed, saying that celebrations like these are put on specifically for tourists and expats, while Cuban citizens, with their meager government-issued salaries, could not afford this event. What I then realized is that the Cuban tourist experience is one that most Cuban citizens will never have—and the life that Cubans live is one that as a visitor, I’d never fully understand.

We walked past the ticket collectors into what looked like a fairy-tale ball, with long tables set with full formal table settings. Once we took our seats, the waiters and waitresses served unlimited wine with our five-course meal, and offered to escort us to the smoking corner if we wanted to take a quick cigar break. As we enjoyed our dinner, famous Cuban dance troupes performed on a stage set up in front of the Cathedral and live bands serenaded us. This was not the New Year’s experience I had been expecting from a country where the average monthly salary is equivalent to twenty US dollars.

After eating, drinking, and dancing our way into 2015, our tour group was ready to head back to our hotel. We walked back through the arches that had ushered us into this revelry, still laughing at my dad’s embarrassing attempts at dancing. I stopped laughing when I realized that surrounding the exit were hordes of Cuban families, hands outstretched, seeking any goodies we might be able to give them. It was a sobering reminder that the experience we’d just had was not one of the average Cuban citizen—it was one afforded to us precisely because we were, in the context of the Cuban economy, rich tourists.

As a tourist in Cuba, it’s hard to feel like you’re getting a real sense of what life is like there for its citizens. Since the ostensible purpose of our trip was to assist the dwindling Jewish community, our itinerary offered a few opportunities that gave us a glimpse into a more real Cuba, including meeting Jews at the local synagogues and visiting a high-risk maternity clinic.

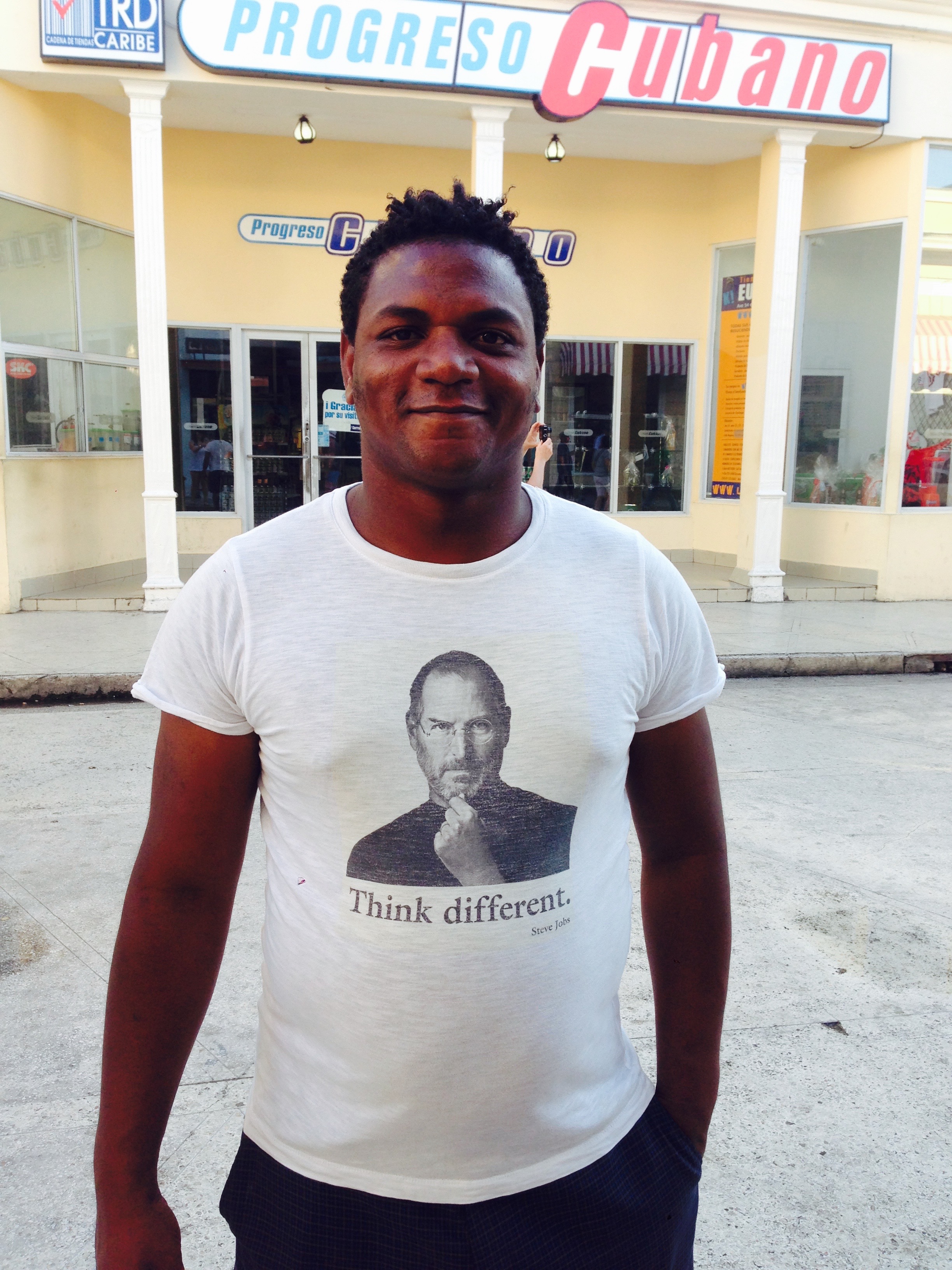

My one experience that truly gave me insight into the life of an average Cuban citizen actually happened when we were at the most touristy place—a souvenir and crafts market in Havana where hundreds of vendors sold the exact same things: fake Cuban license plates, T-shirts with Che Guevara’s face, leather cigar holders, and the like. After wandering the aisles for some time and realizing I wasn’t going to discover anything new, I stepped outside with my brother and dad. A Cuban man came up to us and asked if we were looking to buy some Cuban cigars for much less than they were being sold in the market. Figuring we shouldn’t leave Cuba without some good Cubans, we decided to follow him on a covert operation.

Before we realized how potentially foolish this was, we found ourselves tailing this man through cobblestone alleys, eventually arriving at our destination: his home. We stepped inside the door and straight into the kitchen, where an older woman, presumably his mother, was preparing mashed yucca for dinner. An adorable 4-year-old boy was standing shyly by their tiny two-person table. The kitchen barely fit all of us—it couldn’t have been more than 7 by 10 feet. The guy who brought us there then took out a box of counterfeit Cohibas. My dad haggled a little, paid him. Even if just for a few moments, I was thankful for the chance to deviate from our fixed itinerary and see something that wasn’t on the typical tourist’s agenda.

Despite the relatively poor living conditions, the Cubans we met seemed to be living happily, and were also excited at the prospect of warmer relations with the US—one Cuban man who took us out for a sail on his catamaran in the warm Caribbean water praised Obama, mentioning that the influx of American tourists would be great for business.

In my experience of Cuba the buildings are dilapidated, the cars are from the ‘50s, and the state-produced tomatoes are tasteless, but there is a defiant grace about the country, a faded but resonant glory. It often felt like Cuba and its people were trying to hold on to something that just wasn’t working any longer—though the advent of diplomatic relations with the U.S. may change that, bringing Cuba up to more modern standards. I don’t know what Cuba will look like in the coming years, but from the bit I have seen and understood, the country could stand to raise the standard of living—perhaps not to the level of extravagance afforded to tourists, but at least to the point where citizens can live comfortably and with more options instead of having to subsist on paltry salaries and food rations.

Leave a Reply