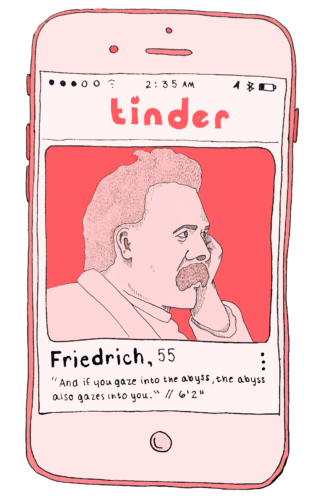

Kingdoms fall, civilizations flourish and die, countries fight for power, yet love never ceases to exist. It is evident throughout history in the iconic V-J day photograph of a smooch between a sailor and a nurse, in Cleopatra and Mark Antony’s love affair, in the seduction of Helen of Troy. Even Dr. Seuss said a few words about love, declaring that “You know you’re in love when you can’t fall asleep because reality is finally better than your dreams.” While most people view love positively, some are a bit more skeptical. Friedrich Nietzsche, the famous proponent of nihilism, believed romance was frivolous and perhaps “the most ingenuous expression of egoism,” comparing it to greed and lust for possession. As I reflected on my failed attempt to find love on Tinder, I could not help but agree with Nietzsche. The experiment only lasted three days, but it has left me with lingering thoughts about love, and why its pursuit on a dating app made me so uncomfortable.

The premise of the experiment was to debunk Tinder’s bad reputation. Given that I have a friend now dating someone she met on Tinder, I thought the project would clarify my perspective on the app. Perhaps Tinder’s notoriety for flings and hookups was misconstrued and one-dimensional; maybe depending on the profile I chose to create, I would receive different types of attention. Unfortunately, I failed to maintain objectivity and let my personal bias against the app get in the way of the experiment, which lasted only three days. Had it continued, I may have obtained more insight into Tinder’s various dating scenes, or lack thereof. Instead, I am left surprised at my own skepticism of not only dating apps, but also of love.

My Tinder experiment started innocently enough on the second floor of Firestone. On that particular Monday afternoon, quiet giggles could be heard originating from a cubicle– instead of doing homework, I was beginning an article for The Nassau Weekly that required the creation of a Tinder account. In 10 minutes, I set up the perfect profile: a photo of me with friends from prom two years ago (in an attempt to portray a social life), one of me vacationing in D.C. (because everyone loves a girl who travels), a picture of an adorable seagull at the Jersey Shore (animals = compassion), and to top it off, a flattering smiling selfie, taken amidst the warm, incandescent lights of Firestone library. My description was cringeworthy and pitiful, but hilarious to me at the time: “Just a gal looking for love in a committed relationship. I enjoy cuddles, laughter and romance!” Next step: swipe right about 30 times per day and track everything on an Excel spreadsheet. After about a month, I would switch to a “party girl profile” full of sexy outfits, girls’ night out pictures, and wine glasses.

Objectively, I have nothing against dating apps– they are a great way to meet more people and expand your horizons. But when I personally started using Tinder, my opinions became murkier. Despite initially planning to swipe right 30 times no matter what, I began to swipe left for the guys I thought were unattractive. I would look at someone’s grainy pictures and formulate my impression of him. I judged, critiqued, and collected. It felt like the Pokémon cards I used to have as a child—I never actually used the cards for real games, but rather selected based on how cute the creatures were. Tinder was my card supplier, and the guys were my collectible cards that sometimes messaged me with hilarious comments.

Unfortunately, dating is not at all like collecting cards. Tinder and similar apps oversimplify the dynamics of human connection. People are never just photos on social media, and their personalities cannot be represented by messages on a screen. Our interest in someone is never as simple as a swipe left or right. Dating apps strip us of what makes us unique—the way we laugh, mispronounce simple words, or walk in a funny gait—until we become one dimensional caricatures of ourselves. They allow us to hide our imperfections and insecurities, and to feign an aura of perfection. The apps skew compatibility into a superficial list of photogenic attractiveness, interests, career, and university. But in the real world, compatibility is complicated. You may relate to someone in one area but not share the same sense of humor. You may enjoy talking, laughing, and being with someone, but lack the same core values. And sadly (it happens to the best of us), you can like everything about someone, but he or she does not feel the same way. Romantic endeavors are usually whirlwinds of emotions, heartbreak, and self-doubt, all of which are eliminated or mitigated by using dating apps. Apps make dating and human connection feel “easier.” But perhaps it is the difficulties associated with obtaining love that make it worthwhile. The failures, emotional turmoil, and upfront rejection allow for personal reflection and growth. We begin to understand our own weaknesses and awkward behaviors, and refine our preferences.

Or maybe, like Nietzsche believed, the inherent nature of romantic love is self-indulgent. Maybe the desire to experience romantic love is out of greed, not altruism. Like most people, I hope to fall in love someday. I want to feel the heat, passion, and intensity. I want to be exuberant, giddy, and high from new love. I want to know someone else like the back of my hand, realize his imperfections, and still love him regardless. But even as I write this, I notice a flaw in my word choice. The use of the word want, which expresses a personal desire.

Nietzsche believed that this desire stems from a greed to possess. By knowing a person completely—their fears, insecurities, desires—you are in a way possessing them, because there is inherent control in that knowledge. The information that lovers exchange is not meant for the rest of the world. The words spoken in whispers on a crinkled bed hold secrets bound by an unspoken pact. Love allows someone to open parts of themselves up that they otherwise would not. Love allows us to possess and to be possessed. When I say I would like to fall in love, I am expressing a selfish desire to feel an overhyped emotion. Whoever “he” will be, I do not care. When “he” comes into existence, I will care because I love him. From the Nietzschean perspective, my care for my lover is not altruistic, but rather egoistic. We love and care about what we possess, and the motivation for this possession is greed: greed for love.

Tinder highlights the possessive quality of love by lining up past “matches” on the top of the screen. Seeing all of my matches made me feel like I possessed the attractive, smiling faces. And I experienced a strange sense of accomplishment, as if each guy were a conquest. Soon, using the app felt like playing an addictive game: the more suitors I collected, the more I wanted—how else can you win the game of love? Ironically, however, I felt no emotion toward the guys themselves—no hatred for those who sent idiotic comments nor warmth for the ones who appeared to be nice. There were thousands of men on this app, theoretically “looking for love,” and I had various potential “matches,” but no interest in pursuing deeper relationships with them. If assessed from a Nietzschean perspective, my experience makes some sense. Perhaps the plethora of possibilities dampened my greed: there is a reason why rare gems are more sought after than common rocks. Or the attention from the comments boosted my ego enough that I did not desire self-validation through deeper connections. With the needs of my ego met, there was no point in searching for real love.

Whatever the reason, it is beneficial to view a positive emotion through a skeptical lens. It is important to understand the limits of romantic love, and to realize that mere passion and infatuation are not enough to create a sustainable relationship. So while my experiment did not work out, its failure has brought its own questions, thoughts, and conjectures. Does searching for love ever lead to finding it? Are humans simply in love with the idea of being in love? How much of love is selfless, and how much of it stems from selfish desires? Although it may be elusive, overhyped, and unsustainable, love will always be around us: in the butterflies and giddiness, in the arms of a lover, in tears from heartbreak. You just might not find it on Tinder.

Leave a Reply