If you walk into the office of the Hawaiʻi Civil Rights Commission at 3:30 a.m. you can find Kanani typing away in her cubicle, hard at work before the sun has even risen. She’s likely donning a grey or dark purple sweater, braving the blasting AC. Kanani exudes gentleness and maternal energy; she wears a calm smile that lifts playfully at the corners. The crinkled skin around her eyes sits under thick glasses frames. I still remember the first time she gave me a hug; it was the first day of my internship, and my hand reflexively shot out each time I met a new staff member, offering the customary formal handshake. Before I could reach for Kanani’s hand, however, she gently pushed it away, wrapping her arms around me instead. “In Hawai’i, we hug,” she said, looking at me earnestly. There is something about her that deeply legitimizes the unquestioned reverence for elders I was once taught but seem to have dismissed as I grew up. She felt familial; and as I learned more about her story, this feeling only made more sense.

The hānai system—the philosophy of chosen family in Hawaiian tradition— is central to Kanani’s ethos. In English, hānai loosely translates to “informal adoption,” but the term fails to capture the intention and history of the system. Its use as a noun and verb encapsulates the versatility of hānai to different situations that may require someone to take in someone else’s child. “There was no such thing as homelessness back then because whenever someone needed help, there was always a Hawaiian family that would come and hānai.”

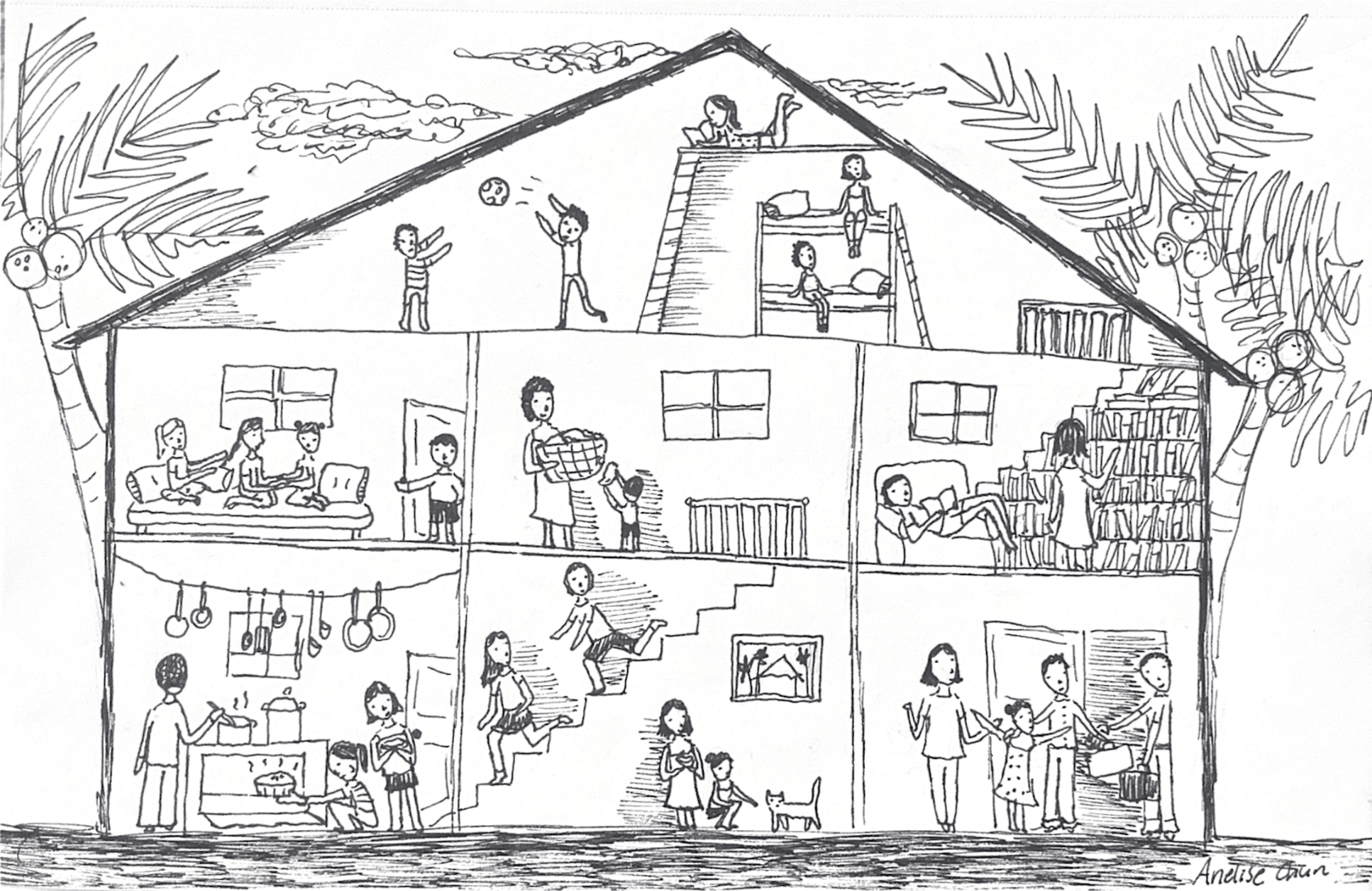

For centuries in Hawaiʻi, grandparents, uncles, aunts, friends or even strangers would take children into their care. It was not uncommon for Hawaiian children to have multiple mothers and fathers. The system is based on the belief that a child can be raised with intention by non-blood relatives, and that these non-blood relatives will provide care and love even without the oversight of a legal process. Hānai was not viewed as giving one’s child away. The lack of legal documentation of the relationship between a hānai child and their family, though, leads to complications in legal areas such as housing policy. The system is starting to gain some legitimacy at the state level; the Hawaiʻi Administrative Rules, 12-46-302, defines familial status as including hānai relationships. Kanani has five hānai children. Kanani explains that there are two ways to take in a hānai. One can either sever the relationship with the birth family and simply rely on one’s relationship with the hānai, or one can maintain relationships with their birth family while living with their hānai family. The second situation would likely occur in cases of extended family acting as hānai.

__

My first long conversation with Kanani stands out. I can’t remember how it began, but I remember Kanani’s eyes glazed over slightly as she narrated a distant memory: her father packing up their belongings in a chenille spread, her childhood cat sitting next to her dolls and other things of innocence that would be left behind, a worn-down car and four bewildered children driving off into the night. She was five years old when her mother left, shortly after Pearl Harbor was bombed.

When she narrated this part of her story, Kanani didn’t dwell on the pain. “My mother left us,” she said matter-of-factly. She focused on her father. “He just tried to think of how he was going to save his family.” Due to Martial law post-Pearl Harbor, Kanani’s father had to be vigilant of the increased surveillance amongst law enforcement who had their eyes peeled for opportunities to institutionalize Native Hawaiians. Children with single fathers, especially of minority backgrounds, were targets for foster care.

So they left everything behind, escaping to the west side of the island to Waianae and Makaha along the coast. This area is known for two things: beautiful beaches and high poverty rates. They lived on the beach until Kanani was in the seventh grade. She picked up maternal duties quickly, caring for her 9-month-old baby sister and her 2-year-old little brother, washing diapers in the ocean. She learned how to cook rice in the sand. “I watched my dad, and I watched how he cared for us, and I tried to copy him, because I wanted to help,” she says. Her father would build a small fire in a deep sand pit during the nights, cover it with sand and place the pallets over it so his children could sleep warm through the night. This was survival. Kanani chuckles as she leans forward to say, “I tell my children, you know, if it ever comes to survival, you’re all gonna come home, okay? Because you don’t know how to survive like I do.”

Kanani kept a low profile, doing her best to maintain it even as she began school. She attended Kamehameha School for Girls. “It was like going to another planet, okay?” she says. “People judge you.” I think it had only been two days since I arrived in Hawaiʻi when I first heard someone say “Kamehameha high school.” The first Kamehameha school opened in 1887, with the purpose of educating Native Hawaiian children, so that they might reach socioeconomic equality with other peoples over generations. Kanani and her sister were accepted into Kamehameha along with children from a variety of economic classes. The dominating influence was still largely Christian. Kanani recalls all the Kamehameha school faculty were white through the 1950s. Hawaiian history was never taught—only American history was in the curriculum. Olelo Hawai`i, the native language, was neither taught nor spoken.

After attending her 65th high school reunion, Kanani excitedly told me someone had remembered her as the girl who sewed her graduation dress. Sewing was just one of the ways Kanani earned money for personal items. Along with cleaning the teacher’s cottage and ironing clothes for five cents each, Kanani worked multiple jobs—at the school library, office, book bindery shop—for approximately 300 hours a year—to pay for her tuition.

My favorite stories were the ones where Kanani would bring up her husband. After several stories it is almost impossible to miss the subtle upturn at the corners of her mouth when she speaks about him. Kanani married a part Hawaiian man who served in the U.S. Air Force and then the U.S. Army Reserve. They were married for 52 years. Her husband was a sheet metal worker and the love of her life. She teared up slightly when she talked about him, but the look on her face reveals that it is abundant joy, not sorrow, that has spilled from her eyes.

Shortly after the birth of Kanani’s first child, one of her classmates approached her saying she was pregnant. The classmate came from what was considered a good family, well off financially and of higher social status. Heavy Christian morality meant having an illegitimate child, one out of wedlock, was unthinkable. To Kanani, someone who picks up family wherever she goes, this woman was like her sister, her chosen family. Now, so was the unborn baby. The child became her first hānai before it was even born. At 18 years old, she took her husband to the hospital with their three-month old baby wrapped in a blanket. At Kapiolani hospital they stood outside the window looking at all the recently born babies. “Isn’t he cute?” Kanani gushed, pointing to her friend’s baby, her hānai, her child. She put the baby boy in her husband’s arms, cradling the head with extra care. “See when you have love, you trust one another.”

Growing up in a missionary-dominated Hawaiʻi, Kanani’s father had been forbidden from speaking his native language. After the last Hawaiian monarch, Queen Lili`uokalani, was overthrown in 1893, a provisional government of American Businessmen passed a law in 1896 banning the teaching of the Hawaiian language from public and private schools. From then on, English was the sole medium of instruction. Kanani herself could only learn Olelo in her congregational church when the sermons were done in both Olelo and English. She shares a lesson that many colonized peoples and immigrants learn painfully in one way or another: “we were taught that you have to learn their way and only speak English in order to get ahead, you have to be like them.” But hānai was an element of Hawaiian culture that constitutes a worldview of what it means to be a family. It could not be taken away.

When the whole world is your family, to take someone in is not a chore. When she was approached by a struggling family asking her to take one of their three children in, she responded, “I can’t separate a family. And so that’s my choice.” She took in all three children. “In Hawai`i, you know, hānai means that I choose you. You don’t choose me. And so basically, it’s a way of always living harmoniously and helping others. In the meantime, you know if they wanted them back, I would have graciously given them back, but they were struggling. And so, it wasn’t temporary, it was real and it was forever.”

Kanani’s philosophy of family applies to her work too. Before becoming the Administrative Assistant of the Hawaiʻi Civil Rights Commission, she had the most impressive list of jobs I’ve heard of. Ranging from positions at Honolulu Iron Works and State Tile Manufacturing, to Executive Director of the Hospital Association of Hawai`i, I could only imagine what her resume looked like.

Kanani’s philosophy of care extends to engagement in the civic sphere as well. She served on various Hawaiian groups including the Waianae Hawaiian Civic Club. As vice chair of Papa Ola Lōkahi, she supported the organization that was the catalyst for the development of a Native Hawaiian Health Care System that can be sustained no matter the form of government. And she’s done all this without a college degree, because when the time came, she sacrificed her college scholarship to take care of her father after his heart attack.

She loves to tell the story of how she was appointed as the Administrator of the Molokai General Hospital: “One day, my boss comes and says, Kanani, don’t come to work tomorrow. And I’m looking at him, I said are you firing me? And he says, no, you’re going to run the hospital. And I looked at him, I said, “I don’t even understand my medical insurance.” She ends this story with a laugh each time, as if the memory shocks her all over again. She says she realized however, that she could do the job because all she had to do was treat the patients as family. According to Kanani, you run a hospital like a home. She learned to collaborate with other hospital administrators, learning how to read financial spreadsheets for the first time. When she found out the hospital’s electricity supplier was an energy guzzler, she applied for a grant with the U.S. DOE. She was able to cover the entire hospital roof with energy savings panels that lowered the utility cost by almost half the amount.

Greeting patients every morning was invigorating. “I would invite their church or families to come sing for them. I would feed them.” She was fired from her job at the hospital because of an irksome bureaucratic conflict of interest, she was devastated. I wasn’t surprised she bounced back from bumps in the road like this, but I wanted to know how.

“Everything that we experience in our life begins in our home. My home was broken. And I constantly get asked, why aren’t you angry? And you know why? Because going through my journey was a lesson for me.” Today, Kanani lives in a big six-bedroom home. She’s divided the entire second floor into three units, and whenever people are in need of a place to stay, her doors are open.

This is how she keeps the hānai system alive, the spirit of unconditional love and chosen family. Come home, she assures her guests, her words welcoming like open arms. “They need to feel that there’s someone out there that cares, you know? That they need now to take responsibility for their life too.” In one story she loves to tell, a new Civil Rights Commission employee couldn’t find affordable housing due to exorbitant Hawai`i real estate prices. Kanani let the employee stay in her home until they were back on her feet, going so far as to leave her guest in charge of the house while she traveled. Her chosen family receives her care and unconditional love, and with it they are bestowed with the responsibility to carry it forward.

She speaks of her children with so much pride. They’ve all settled down and work all over. One works as a schoolmaster in Taichung, Taiwan, and another as an air traffic controller in Honolulu airport. No matter where they go, they always come back to visit, bringing their children and now grandchildren too.

At this stage in her life, Kanani is learning to slow down, taking time off of work to see her son Kalani, who was diagnosed with cancer. She wanted to bring him home to take care of him. “My hānai son Sam and his wife and my grandchildren said no.” They wanted to take care of him themselves, Kanani remembers with pride. “That. That’s my report card.” After listening to Kanani’s story, I still can’t fully wrap my head around how she survived. But the one thing I gathered for certain is that the centralization of hānai in her life screams unconditional love. It’s the lesson of every story she tells and a lesson I have to learn.

Leave a Reply