Sasha awoke too soon for his liking. He felt as if he’d seen the sun rise but an hour ago, when really the waning effects of wine had enabled him to soundly sleep away the past few. It was near eleven now, and he’d forgotten to pull the curtains tight before exhaustion had brought about his clumsy falling into bed. With a groan and a grimace, Sasha rolled onto his right side and clamped his eyes shut. He couldn’t remember if he’d dreamt that night (not that he’d spent the vast part of those dark hours asleep…). He did remember Mila, of course. But there was no narrative within which to place her. No nightmarish fire to save her from. He wondered, too, how many of these undreamed dreams remained in his lifetime, waiting to plague him in his conscious and unconscious states alike. Sasha blinked and wished he hadn’t. He noticed an empty bottle lying on the floor of his cramped bedroom, a slight pool of sticky liquor still trapped inside. Drops of the alcohol had oozed out, marking his crime.

A stroke of panic seized Sasha, and he curled his knees closer to his chest. Pressed his eyes shut even firmer. Letting a few seconds trickle by (he counted them in his mind), he opened one eye slowly and then the other. The bottle was still there. Sasha pushed himself up and winced. The bottle’s comrades stood ominously –all lined up on the ledge of his dresser and staring grimly down at Sasha and their fallen brother on the floor. He managed to roll out of bed and crawl on his knees (why did he feel sick?) to grab the lone bottle. The splintered floor hurt his bones and his palms. Instead of placing the latest veteran amidst the rest of his collection, Sasha threw the bottle with a hurried movement into the corner bin. Had this sudden urge to swing his arm back and swack the remaining trophies to the floor. Watch the glass shatter before him. Then, he might walk barefoot across the broken pieces and see how bad it cut. Whether it would at all. Or, he could throw them out the window, and see how his neighbours might react to his hooliganism. Somehow though, he couldn’t bring himself to do it. The empty bottles represented now the memories which might otherwise have slipped away with all the sips –gulps, if Sasha was being honest– he’d taken each night he brought a bottle home. He didn’t remember bringing one home this morning, though.

A sharp knock on his door reminded him it was Sunday. Its cause didn’t wait before decidedly marching into his room.

“What this mess?” an old woman’s voice scolded, catching Sasha still standing sheepishly by the bin. Her th buzzed its angry accusation into his ears.

Tamara had a knack for assembling narratives out of people and objects relatively placed. She took one look at Sasha’s weary state and frowned. He shifted his feet and threw a nervous glance at the bottles, in their stoic row. Tamara followed his gaze, frowned further, and whipped her head back around at Sasha.

“I told you, chłopiec…I told you, did I not? Enough with this drinking! And on Sunday too…Boże!” She brought her hands to her cheeks in exasperation and shook her head. Dragged this last word out, making it buzz with remarkable condescension.

“Come on, Toma. It’s only wine!” He joked. “One of our good Lord’s many miracles! Besides, I drank it before the sun rose. And if the sun has yet to rise, can we really name the day?”

“Oh, you think you funny! You think it joke! You think I laugh when one day I walk in here and you not wake up?”

There she goes, thought Sasha, getting herself all worked up. Tamara continued to spout such exclamations, a kettle under threat of fire, until she rapidly turned around and stamped out of the room. With a heavy sigh, Sasha followed her out, already wondering what route of atonement would work best this time. It was probably too late to make it to the flower market and find her favourite poppies (and they were no easy feat to find!). He had spent all his remaining wages last night, too. Perhaps, he could bake something while she was out for her daily walk? Sasha didn’t have any flour, though. Only a few eggs and a pat of butter tucked somewhere inside the fridge. He’d have to use her pantry. Or, maybe pain perdu might make for a passing sorry? Would such kindness count? Does any kindness, made in apology, mean much on its own?

She was sitting now on the kitchen stool, staring bleakly in the direction of the balcony which opened out onto the lazy street below them. Sasha was lucky to have a balcony of his own, however slim it was. It was one of the nicest things about his flat.

“How’d you get in, Toma?” asked Sasha.

“Door open,” she shrugged. Right. Had he not locked it?

“I mean, why?”

“Sunday.”

Sasha’s already pale face lost whatever hint of colour it had left. He remembered now what Sunday meant. What it meant to Tamara.

“Ay, Toma. I’m sorry. I promise next week I’ll go with you, no doubt about it! I promise!”

“More you speak these words, chłopiec, more I think I hear parrot talk. I promise! I promise! I thought promise is what people do, but all you do is break! You just repeat these words. Promise! Promise! Pfft.”

“Oh Toma, don’t be like that. It’s just, I’ve been having some real trouble sleeping lately, and, you know how it is…I just couldn’t bring myself to get up. I think I might be getting sick or something, really…”

“Oh yes, I would sick be too, if I spend my nights sitting in cold park with cold bottle and come home in morning like drunk.”

Sasha winced. “You heard?”

“Of course, I hear. I may be old, but ears work!”

“I’m not a drunk, Tamara.”

“Well, that is what drunk say.”

“That’s not fair!”

“What not fair, I say! I say, why is Kiełbasa dead?”

This took Sasha aback. He’d been ready to defend himself. Explain away yet another week of missed liturgy. What had dead Kiełbasa to do with it all?

“Kiełbasa?” he repeated.

“Dead,” Tamara shook her head.

“I know…He died a long time ago, Toma.”

“I tell you why.” It wasn’t a question. Nervously, Sasha drew nearer and sat across from Tamara, cramped at the tight table.

“My husband killed my boy and my boy killed my dog and bottle killed them all.”

“What?” Sasha gasped. “But your son is alive, Toma!”

“Mmm, no. Not my Ilyusha.”

“Ilyusha’s in Kraków. Right, Toma?”

She shook her head more passionately.

“I tell you, chłopiec, why Kiełbasa is dead! Oh, how I miss that dog!”

“Okay, Toma. Tell me.”

“I do not like talking about my misfortune, you know.”

Sasha nodded along.

“Kiełbasa died long time ago, but truth is my boys died before she did.”

“Your husband died in the army though. Remember, Toma?”

“That was his body that died. His spirit died even longer before.”

“What now! How do you mean?”

Tamara stood with a jolt. “I make tea,” she announced. “No tea, no story!”

“Very well then. Let’s have tea.”

Briefly, Sasha considered rising to help her. He knew, though, she’d only tsk and smack his hand away. She’d call it meddling.

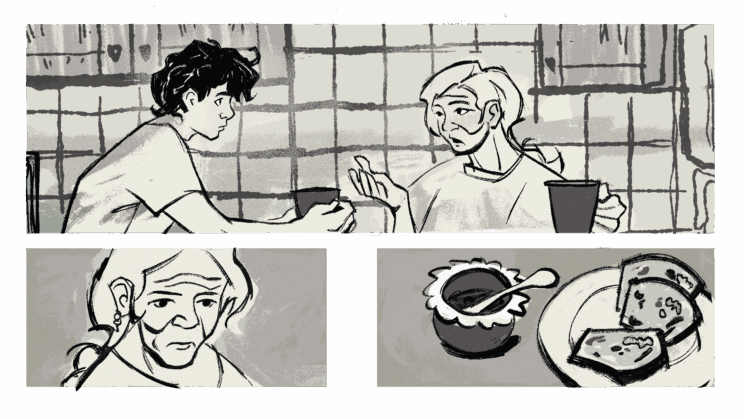

“Jam, we need jam,” he caught her muttering. She shuffled out of his flat, and he heard the clinking of rusted keys as she unlocked her own door across the landing. Seconds later, she was back with a quarter-eaten pot of that cherry jam, along with a round bulge wrapped in aluminum, what Sasha imagined to be yesterday’s loaf. Of course. Tea with no sugar really meant tea and some sugar, albeit in a refined form of sorts. He watched as she coaxed the gas flame to a gentle awakening, then placed the tarnished kettle on top. She started cutting thick slices of bread (wheat…raisin, with walnuts woven throughout), opened his fridge without asking to retrieve the butter, and placed both on the table before Sasha. “No cheese?” she raised her eyebrows. He shook his head.

Before she could scold him further, the screech of the boiling kettle took Tamara back to the matter of tea. Carefully, she poured the hot water into another painted blue pot she’d prepared with aromatic leaves of jasmine, raising the kettle slightly as she went, so the water poured elegantly down from its height. She set the pot, the jam, and two cups on the table as well. “Eat,” she instructed.

Sasha grabbed one slice obediently and began to cover it in generous spoonfuls of Tamara’s jam. Took a bite –mistake. He remembered his manners and poured a cup for Tamara first, then himself. Took another bite to demonstrate his gratitude –he was famished, despite his sickness, and cast a sheepish smile at her. “It’s very good, this jam.”

Tamara scoffed. “Tell me something new.”

“I think you’re the one that’s got some telling to do here.”

She looked away from him, that wistful stare casting a shadow across her withered face again. Sasha wondered how long she’d let the silence stretch. It wasn’t uncomfortable, only palpably sad. He sensed if he were to move or say anything before Tamara was ready, nothing but emptiness would come out.

“My husband would come home like you did,” she voiced suddenly.

Sasha found he was holding his breath, not daring to break his side of the unspoken agreement. She was still looking away, at something far beyond whatever Sasha could see through the window. He followed her gaze, catching a glimpse of a black cat’s sinewy body slipping around the street corner.

“I feel sad,” she began, “when I think of how you mirror his footsteps. We married around this age, you know? My father did not agree to it. Said no good would ever come from marrying son of chauffeur. In end, no good did come of it. I was happy, though. I thought he was too…”

She was focused on Sasha now, her sad grey eyes watered-over but refusing to spill their salted grief. He widened his own eyes at her. Bowed his head ever so slightly. Go on, he meant. You can tell me.

“That is how I met him, you know? My father on good terms with his father –he agreed to drive me to railway station that day. I took train into city, so I could sit for my exams. And Slava was in car too, and he was there when his father come to get me afterwards. That is how it all started. Well then, Slava asked me for walk in park not too long past that. I said no because I knew my father would not like me getting on with son of chauffeur like that. But he asked me again, and again, and after sixth time, I agreed, so he would stop nagging me. What harm, I thought.”

“And you fell in love?” Pure instinct, and Sasha thought of Mila. She was love if he ever knew it. Did she?

“Bah, love! People do not fall into things like that, chłopiec. Love happens to you, but you do not fall into it. No.”

“Well, what then?”

“He asked when he could see me again, of course. I told him I could not. I was waiting for my exam results, you see. I was going to city for university. My mother worried greatly about this. My father was proud, though, and how I wanted him to be proud!”

“And did you go?” Sasha pressed, curiosity triumphing well over his prior vow of private silence.

“I did, yes. I got my results after few weeks, and that autumn, Slava’s father drove me to railway station, with all my bags this time. Slava did not come. He was mad. Really, I think part of him resented me. I had better English than him…he could only ever stay as son of chauffeur.”

“You liked it though?”

“Oh, it was difficult work, Sasha! City does not welcome those who are not native to it. That is its trick. But I did my best, got passing marks. All was well, until it was not. My father passed away that winter, you see. I had to come home. My mother…she could not support family without him. Slava was at station when I come back. He was one that drove me home this time. Sat with me in that rusted old car as I cried and cried. Very next day, he said he will marry me. Help my family and all. If only I was okay with son of chauffeur. He said, he take care of me…good care. And well, what was I to do? I believed him. And Slava was never liar. That same evening, he was assuring my mother how I never want for anything more with him by my side. Promised portion of his paycheck be sent to her and to my two younger brothers –every two weeks! My poor mother…she agreed. And week after that, we buried my father, and week after that one, Slava and I were signing our papers in little town hall. We did it quick. Only family at funeral –and Slava and his father, of course. We could not afford larger wedding. It was December. How cold! I remember it was snowing both days. I remember my mother told me she never seen sadder bride.”

Here, Sasha wondered what possible connection Tamara was going to draw between him and her dead Slava. Where would this tale lead? Did she suspect something about Mila?

“Slava kept his promise. No good ever did come out of us, but he was never bad. Just broken, broken man. Work got to him, as it often got to our men. He was out there driving all hours of day and night, trying to scrape up enough to support us –my family, and his own too. I did not go back to university. Stayed home…in kitchen most days. All three families were often hungry, you see. Slava’s parents soon got sick too, and Slava never had siblings…save for older sister who left them long ago. We never spoke about her. I do not even think he knew where she was. So Slava drove, and I stayed home, made soups…lots of barszcz and kapuśniak, of course…plenty cabbage, kasha…on good day, I make kotleti or gołąbki too. We invited my mother and brothers over on those days. No one was full though, even on good days.”

Sasha set the piece of bread on his plate, not taking another bite. Tamara wasn’t paying attention –she was back to staring out the window. Perhaps, it really wasn’t Sasha she was talking to now.

“We had Ilyusha within year,” Tamara continued.

So young! thought Sasha. She must have been not much older than he was now…than Mila. Younger even.

“Oh, that boy hurt me even then! Terrible pain, it was! Most my poor girl-body ever felt. Only soul knows pain greater than that Sasha…only soul and only God! And how Ilyusha cried! He cry, and cry –all night! I could not sleep, neither could Slava’s old parents. But we got on…you always do. Slava kept driving. I became very ill. I thought Ilyusha would be true death of me –in birth, he take all my strength! My mother moved in with us too. Did all cooking now…cleaning, shopping. Slava arranged for my two younger brothers to go live with distant cousin in city. He was doctor, not rich, you know…but no family of his own. That was last I ever saw of those boys. Oh, I was ill for long time! For two, three years, I was very weak. But Slava kept driving, and there was one less mouth to feed now…and another had smaller appetite, thankfully. We got on. You have to!”

A loud yowl from somewhere below interrupted Tamara. An even louder merde! followed, and Sasha wondered what that cat was up to. He took the pause as the opportune moment to refill their cups with tea. His stomach growled, but it was only the expression Tamara made that let him take another bite of the bread. How did she make jam like that?

“You best eat, chłopiec!” she scolded. Took a deep sip of tea herself and carried on with her memories. “When Ilyusha got to be four or five, things were going bit better. Even looking up, we thought! Slava’s parents had passed away in meantime…old age, what can you do? My mother was now the only one still living with us. Our last surviving family. Slava even got slight raise. Oh, I remember that day! He brought home tastiest cake and bottle of żobrówka! We got drunk that night…Slava and I. His kisses tasted sweet. I remember that too. Oh, but that bottle was bad luck…I know it.”

“How’s that?”

“He got his summons not long after that. Duty called, or so they say.”

“You mean he had to go fight?”

“Yes…and no. First, it was training, and when he come back he was already different. I saw it in his eyes…they were dull. And when they let him off again for bit, he returned with two bottles this time…drank it all himself. I tried to ask him. What happened, Slava? He would not tell me. Just shook his head. Soon he had to go back. This time, it was real fighting, and it was longer until we were able to see him again. Over year…it was just Ilyusha, my mother, and I. Ilyusha went to first grade. Slava was not there to see him off…. When Slava finally did come back, he was worse. Five bottles this time. Slava, tell me what they did to you! I cried. His kisses were acid and harsh. He would not tell me anything! Slava, where did you get money? Slava, we are hungry! Anyways, he got money from promotion. They kept him, you see. He go off every few weeks to train new recruits now, and his eyes were duller each time he come home. One day, I got very angry. He promised he take good care of me all those years ago…and he thought money was care enough. But no! How could it be? Ilyusha barely knew his father…barely saw him. One day, I was very angry indeed, and suddenly, I fainted. Must have been from this rage…or something like that. It scared Slava though…I saw that son of chauffeur in his eyes again when I woke, and so I begged him. Slava, think of Ilyusha! Ilyusha needs you! You must spend time with your son!”

“But he couldn’t? With the army and all?”

“He could not,” Tamara pulled her wrinkled handkerchief out of her apron pocket and blew her nose. “He could not, you see. They kept him away so much from us! But next time Slava come home, he brought more bottles, of course, and –to my great surprise– he brought dog!”

“A dog?!”

“Yes, would you believe it? I was shocked, as was my mother. Slava, we can barely feed ourselves! And you bring us dog? But he was stern. This dog is my gift to my son, he told me. And he took Ilyusha with him that night on long, long walk…late into dark hours. I was worried, stayed up whole time waiting. Sat on balcony keeping watch, you know? And I heard him tell Ilyusha below…their voices barely drifted up to me from apartment landing, so I had to listen close, before they went back inside. Ilyusha, he told our son. You must do your best to take good care of this dog, you hear me? You must treat Kiełbasa with same kindness you would show any person…with more even! Treat Kiełbasa as you would treat your father! Love this dog in my stead! Show her good things in life. You hear me, chłopiec? Ilyusha must have been six or seven then, so young…And Slava, well, he left next morning, after spending night with his bottles rather than me. I cried myself to sleep that night…I was so sad! And scared! How I wished Slava did not have to go! But he done his part, in his way…had his word with Ilyusha, like I asked. Kept sending us money. My mother was taken care of… My brothers had better life in city, somewhere…Ilyusha was sweet boy, always play with Kiełbasa in yard after school, and made sure she had water in her bowl. He sneak extra food to her under table, and begged me to let her sleep inside with us. I almost thought Slava knew what he was doing, you know? That he left us Kiełbasa as an apology. Sorry, I can not be here. At least, I let myself believe that. But I never saw him after that night.”

“Oh, Tamara!”

The old woman blew her nose again. Still, Sasha could not bring himself to cry. Couldn’t bring himself to take another gulp of the tea either. He felt hot, and even Tamara’s miracle jam wasn’t sitting too well inside him.

“Training accident. Despicable. Apparently, he drank that morning. Did not have his senses about him.”

“That’s horrid!”

“What can you do? I lost Slava long ago. I knew it. Oh, but I still cried when I heard news! Poor Ilyusha had never seen me in such state. I had to find work quickly though, now that money would stop coming. Luckily, I was always good in kitchen…and they always hiring cooks. I became chef at School #33 soon after. There was slight compensation thanks to Slava’s position, but most of that went towards funeral, and then Ilyusha needed winter coat, and we had to feed ourselves, and poor Kiełbasa too. Oh, but this was not even worse of it all, Sasha!”

“What more?” Sasha gasped.

“Oh, but he did not mean it! How could he have? Ilyusha had always been sweet, sweet boy. Only meant well. He was doing what his father had last told him, you see. For I remember those words myself! Treat Kiełbasa as you would treat your father! Slava had instructed. Love this dog in my stead! Show her good things in life! Ilyusha was so young…he could not have known…”

“What is it, Tamara? What happened?”

“Well, we lost Kiełbasa within year too. That winter. All dies in winter, does it not?”

“She got sick? Too cold?”

“It was Slava’s words that made her sick. Made my Ilyusha sick! I would never have imagined! And what kind of shop owner sells bottle to kid like that! They do anything for money…”

“Tamara, you must tell me straight! What happened?”

“Ilyusha got bottle, and he gave some to Kiełbasa while I was away. I come home to find my boy and my dog in yard that evening. Poor Ilyusha was in tears, and Kiełbasa could barely move. It was her and that half-empty bottle, lying spilled over earth. Stupid dog! No sense of self-preservation. Ate everything in sight. And drank everything too! Couldn’t blame her for it either. I had my mother call vet as soon as I come back, but there was nothing to be done. Intoxication, vet proclaimed. As if I could not determine this myself. Next day, we buried another. Winter again. Where did you get it, Ilyusha? I asked my son. He said man at market give him discount, and he take money that morning from my stash! Why, Ilyusha? I asked my son. And you know what he told me? He said Papa loved bottle! Of course. Show her good things! And dogs do not know. It is same with chocolate… ”

“And what happened to Ilyusha, Toma?” Sasha moved his seat closer so he could hold Tamara. Her body heaved with sobs as she leaned against him. He couldn’t quite believe what he was hearing. But he knew better than to doubt her. He’d lived enough to know all kinds of sadness were real.

“Grew up. Bought more bottles. Thought he taste something good inside them! Chasing after his father! It is no good when boy grows up without his father, you see!”

Sasha didn’t know how to ask his next question. Whether he should at all. Where was Ilyusha now? he wondered.

“Dead,” she read his mind.

And the bottle killed them all, Sasha recalled Tamara’s prior words.

“He was only fourteen. Can you imagine such thing, Sasha? My entire family! And you keep tempting fate! Testing your good fortune!”

Sasha knew, too, that his next thought was unkind –and unfair. The automatic part of him –the one that thought not, felt not– was mad at Tamara. How dare she tell him what to do? How dare she compare him to her dead, drunk husband? To a stupid dog? A mere school boy? Did she think him no better, no wiser?

“Do not ever let me come home and find you dead like that, you hear me, chłopiec? That is sight I never wish to see! Boże!” Another sob.

A pang of guilt twanged through Sasha’s chest. How could he? It was wrong to think these bad thoughts of his. It was wrong to make Tamara suffer any more.

“I promise, Toma. Come on,” he attempted another one of his jokes, “you think that ol’ bottle can get me like that? Have some faith!”

“Faith, ha!” she exclaimed, “You think it joke! You think this funny! Let us see then, jokester, who is laughing in grave!”

“Toma, you’re getting yourself all worked up now. Here, have some more tea. Let me put on another pot. That’s what you always say, right? Tea can’t not make it better?”

“Hmph,” she sniffled. Loudly.

“There now. Have some more of this marvelous jam, please. Some bread. You need your strength! And you still haven’t shared the recipe with me!’

“Ha!” she exclaimed again. “It is secret.”

“Aw, Toma! Don’t be like that! What will it take?”

“Throw bottles away.”

“What?”

“You heard me…clear those bottles out of here. And I give you recipe. In fact, I insist. Or else, you can say goodbye to this jam.”

“Tamara, you’re not my landlord!”

She gave him a look then, the kind that made Sasha realise she may very well hold more sway over him than any landlord ever could.

“You do not need to be seeing those. It tempts mind.”

Sasha sensed another wave of anger stir within him –how it started to boil deep inside– and made to cool the flame. “Fine.”

They finished their tea in silence, their spoons clinking noisily as they took to stirring drops of the jam into their final cups of tea.

“Well,” Sasha offered, “Thanks for the tea.” He didn’t thank her for the story, if one could even call it that. Stories had the illusion of happy endings. Or so, Sasha had once believed.

“Mm,” Tamara raised her eyebrows. The command was clear.

Half-heartedly, dragging his feet, Sasha pulled the rubbish bin (the one in his bedroom was embarrassingly full) out from where he kept it hidden beneath the kitchen sink and took it with him. He cast a last, longing glance at the empty bottles –his roommates, really! They’d shared the space with him all along– before starting to remove them, one-by-one, taking care to make as much noise as possible, so Tamara could hear the harsh clatter as each bottle joined its fallen comrades. Somehow, it got easier as Sasha went along. Slowly, the troop diminished in number, and Sasha was starting to think that, really, this wasn’t so bad. Not like he ever kept flowers inside these desolate vessels anyways.

It wasn’t until he got to a particular bottle, clear glass hollowed of prosecco, that he found he could hardly breathe. Mila! He couldn’t.

It wasn’t his bottle to throw away.