This is not the story of my name, but it is the story of my birth.

On the night of October 31st, in the sleepy suburbs of Paris, my mom feels her first contraction. She wakes up my dad. I am the second child, and this has been rehearsed. He pulls the old-school Fiat out of the garage. My mom lies back on the pre-reclined front seat. She sweats through her distended law school shirt. My dad does not speed, but it is late, the roads are clear, and the thirty-minute drive goes by quickly. They cannot wait for their baby boy.

By the time my dad parks in front of the Hôpital Americain de Paris, which is actually not in Paris but in Neuilly-sur-Seine, my mom is no longer sweating. She turns to him and smiles sheepishly.

“I’m sorry. I was just hungry.”

Few places are open at this time of night, especially in this residential suburb. My dad drives down the tree-lined boulevards and into the city. They find an open kebab place on the Champs-Elysées, across from Le Queen, a nightclub for queer men.

The sun is rising on the Champs.

Men parade out, in twos. They teeter on five-inch heels, lipstick smeared down their chins, torn fishnets highlighting the swollen muscles of their calves.

My parents share a basket of cheese fries.

***

On November 4th, in the early morning, my mom is sitting up in bed. The car is out in the street. Weary of another false alarm, my mom is slow to put on her slippers. Her robe doesn’t quite close over her stomach, and the elastic band of her pajamas leaves red marks on her skin.

They are caught in morning traffic. The drive that had felt so quick a few days ago now drags on. My dad is stuck on the périphèrique, the highway that rings around Paris. Motorcycles weave by the stalled cars. My mom is in pain. Her face is red and her eyes are shut and she breathes heavily. He taps his knuckles on the steering wheel. Though my dad is kind, he is not soothing, and he grumbles French swearwords while simultaneously trying to calm my mom down, but my mom is not hysterical, she never is, and even in child-birth she is composed, but she holds her face in her hands.

Bono croons on the car radio.

My mom does not start yelling until they park in front of the hospital. She is surrounded by nurses who whisk her into a room, pat her forehead dry, swap her flannel robe for a plastic hospital gown. My dad speaks loudly so that she knows he is there, but I imagine his eyes are turned toward the ceiling.

A doctor walks in with a flutter of his lab coat. He looks at mom and compliments her for foregoing an epidural.

“It’s rare these days that women want to give natural birth. I really admire that.”

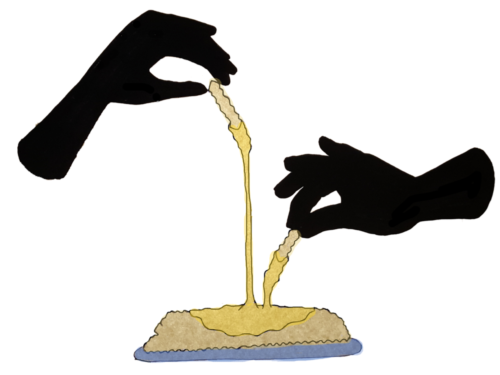

This is the first that my mom has heard of foregoing an epidural. She has no intention of doing that, but it is too late, and I’m on my way out, toes straining toward the exit, little hands clawing their way to the light, clumsy fingers unraveling the umbilical cord.

“THIS [breath] WAS [breath] NOT [breath] MY [breath] DECISION [heavy breath]!”

In the hospital, my mom is nicknamed “the opera singer.” Her screams reverberate through the halls, echoed by the other pregnant women in the maternity wing, a heavenly chorus that welcomes cherubs into this antiseptic world.

Within a few hours, I skedaddle out of the amniotic sac.

To my parents’ surprise, I am not a baby boy. They have not picked a name for me, and for the next few days, I am “petite fille Pauchet.” Little baby girl, bald ball of blubber, only too happy to sleep and to suckle. I perk up when I meet my older sister, and already I think I look up to her, goldi-locked two-year old perfect princess, svelte and supple, fromage- and purée-eating child.

I am bald for the next two years of my life.

***

After some pressure from concerned nurses, my parents eventually name me. They challenge themselves to bridge two cultures in me, the French and the American, to give me the flexibility to navigate these identities through my name as a passport to the world.

Or so they say. I suspect that they gave me two middle names to make up for their uncertainty about the first.

Madeleine, Maddy, Madz, Mad-dog, Madhu, Maddydou. Constantly misspelled, and hated for years because of the association with the cookie, as though I needed another reminder of my baby pudge in a world of stick-thin French five-year-olds.

Elizabeth. My mother’s name. Technically, Mary Elizabeth, though she’s never gone by Mary. My dad calls her Zaza, her brothers call her Beth, but I’ve never owned the name or thought of it as part of my identity, other than as a clunky side-note to a multisyllabic stutter.

Anne. My godmother’s name. There is a murky, misunderstood story about how my parents met my godmother, but it involves snobbery, parties, and scandal. I can get behind that.

Pauchet. Poh-shay (kind of). Most people I speak to lack the phonemes/will to get this right. I’ve tried hard to make “pocket” happen, but like “fetch”, it’s not going to happen. Instead, I am stuck with pow-chet, followed by a snicker, followed by a glare. But I am attached to Pauchet. I hold it up as a testament of my Frenchness for those who doubt me, as proof that I am both American and French and that I sound both American and French, and that whether my name is Madeleine Pauchet or Maddy Powchet, I belong to both communities.

Like me, my name teeters between two identities, as graceful as a stumble home the morning after Halloween, as happy as a basket of cheese fries shared between your parents.

Leave a Reply