It’s been a fast month since I got back from my year off in Korea, and it already feels as if I were never gone. What strikes me most about being back in the Bubble is how narrow a perspective I had before I left, and still have now despite the time away; when I look back on my freshman- and sophomore-year self, I see a little goldfish swimming around in a bowl, perceiving the various little structures in the bowl — the castle, the pebbles, the small scratches on the glass — as the whole, self-important world. And when I look back on my time in Seoul, I am most grateful for the hours I was able to spend with my grandparents, listening to their stories and learning what to prioritize in my own life. Grandparents are bastions of wisdom and pure grit. What we continually forget in our soft, wired age is that people who lived before Amazon Prime and Netflix and iMessage had to make do with very little—my grandmother loves to recount that when she made appointments with friends, she would tell the other person that if she wasn’t there within 20 minutes of the appointed time, she was probably dead. None of these text messages with variations on the theme of “sorry, but can we reschedule because I just realized that I have a lot to do.”

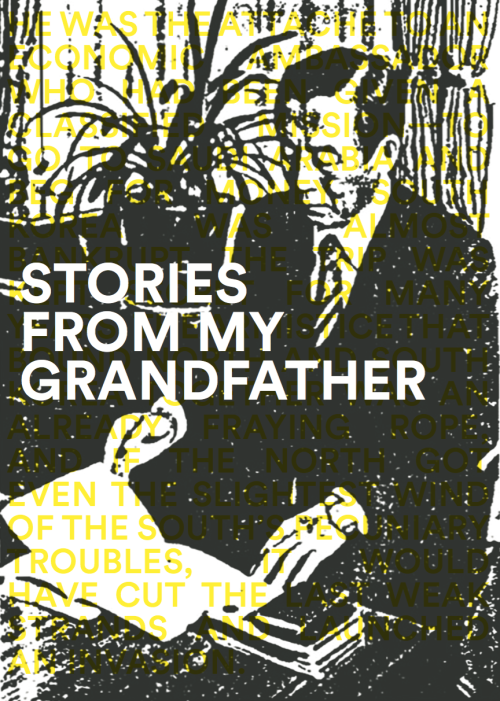

Let me share with you how, in my grandmother’s words, my grandfather played his small part in the country’s rapid advancement. (I would never have been able to coax this story out of him directly — partly because he hates talking about himself, but mostly because his memory was damaged by a severe bout of malaria while he was serving as a Korean company executive in rural India, back when remedies were scarce.) The year was 1975. My grandmother had recently given birth to her fourth child, and my grandfather, always more of a family man than a career man, was just beginning the steep ascent to his professional success at age 39. He was the attaché to an economic ambassador who had been given a classified mission: to go to Saudi Arabia and beg for money. South Korea was almost bankrupt. The trip was kept secret for many years; the armistice that bound North and South Korea together was an already fraying rope, and if the North got even the slightest wind of the South’s pecuniary troubles, it would have cut the last weak strands and launched an invasion.

The team was hurriedly assembled and dispatched to Riyadh, Saudi Arabia in mid-March. To everyone’s relief, King Faisad bin Abdulaziz al Saud, known for his anti-Communist and generous foreign aid policies, was sympathetic to the South Korean cause. He promised to provide today’s equivalent of $US1 billion in loans. After all the hands had been shaken and the photos taken, my grandfather and his colleagues did what all Koreans do best and whiled away the evening in a drunken euphoria, declaring themselves the saviors of their country.

The next day, all of them but my grandfather boarded their homebound flights with massive hangovers. As the lowest-ranking diplomat of the group, he was left behind, also hungover, to deal with the paperwork and official ratification. I can picture him now: squinting at the documents through fashionably round glasses, his thick eyebrows knotted at the center of a younger forehead. The aging of this forehead would be accelerated by the events of the next few days.

On March 25, King Faisal held his weekly majlis, where he would open his home to citizens and foreign leaders who petitioned for reforms. His nephew, Prince Faisal bin Musaid, stepped quietly into the waiting room and exchanged pleasantries with visiting Kuwaiti officials. When it was his turn to go in, his uncle smiled and extended his arms for an embrace. Prince Faisal kissed him, reached into his robe, and pulled out a revolver. Three shots rang out in the hall. The first went through the king’s jaw, the second through his ear. The third missed and hit the ceiling, but the king had already slumped to the ground. A nearby guard struck Prince Faisal with a sheathed sword and arrested him. (Some say that the prince was insane; others claim that he was avenging his brother, a fundamentalist activist who was shot dead by the police in a riot against Saudi Arabia’s first television station.) The wounded monarch was rushed to the hospital for a blood transfusion, but the bullets had done their work. He died soon after. An emergency meeting was held by the royal family, and King Faisal’s younger brother, Khalid bin Abdulaziz, was named the successor to the throne. The government was to be shut down for three days in mourning for the late king.

Alone and dumbfounded, my grandfather watched as the future of his own country potentially unraveled. What was he to do? Would the new king even give the time of day to this lowly South Korean envoy amid all the chaos of the transition? The late Faisad had only authorized the loan transaction in word; nothing had been signed, and my grandfather had little hope that the Saudi Arabians would remember the pleas of so small and poor a country after all that had just happened. But the fate of his nation now rested on him. Submerging his terror in years and years of diplomatic training, he requested an audience with the king.

King Khalid, the fifth and most mercurial son of the bin Abdulaziz clan, was known to give orders in government just as he gave them at the dinner table. What impressed the royal family at these gatherings was the play of his forefinger: being careful not to point, he would maneuver it, half-bent, over the pita and the kabsa and the olives, so that the designation remained imprecise and the servants had to guess at his commands. My grandfather had many reasons to be afraid. Let us now cut to the moment he steps past the bodyguards and into the royal office, dark patches spreading on the back and underarms of his suit. He shakes the imperial hand. But the outcome is already being decided in an instant that my grandfather will later, after he has converted to Christianity, attribute to divine intervention. Perhaps it is my grandfather’s slow gestures and easy smile that warm the king’s heart. Or perhaps it is his laugh, which splashes the moment with all of its deep staccato resonance before it subsides. But in a second, inexplicably, the two men take a liking to each other. They sweat together over steaming cups of gahwa coffee in the late-March heat and speak of their experiences abroad as attachés. Maybe the new king is thankful for a diversion from the stressful events of the previous days, or maybe he wants to begin his reign with a small accomplishment; in any case, within the hour he has signed the precious papers in my grandfather’s hands with a flourish of fraternal benevolence. On the other side of the continent, a whole nation breathes a sigh of relief.

When my grandfather finally returned to Seoul with the signed loan agreement, it was not just his immediate colleagues but also the entire Finance Ministry that got drunk with him in his honor. So the story ends happily. The country was eventually rebuilt, my grandfather was promoted big time, and his childhood home in the southwest of Korea was made into a small national treasure. And here I am, two generations later.

Leave a Reply