Although it’s impossible to say how much of herself Sally Rooney injects into her work, her debut novel, Conversations with Friends, comes across as the troubled inner monologue of a Rooney surrogate – naturalistically pretty, palatably Marxist, and a keen observer and patient translator of the contemporary Irish social scene. Detailing an affair between Frances, the narrator, and Nick, a married older actor, Rooney’s unconventional love story approaches intimacy and affection through a feminized Marxist lens, balancing an intellectual disdain for heterosexual power structures with Frances’s naive belief in a fairytale ending for herself and Nick. The result is knife-like in the stomach of any twenty-something girl; Frances’s fraught romantic relationships, family troubles, and feminine self-loathing occur parallel to a grisly endometriosis diagnosis. Her coming of age is, in many ways, a painful molting.

Communication between Frances and Nick occurs both in-person, often at glamorous social functions, and over email, painting a portrait of the hybrid on and offline relationships that characterize contemporary dating. This novel found me at a time where its meaning felt maximal; I read it on an airplane, flying back to college after weeks of spotty connection with my school friends. I had complementary Alaska Airlines cell service, and I kept an ongoing dialogue with my boyfriend about my nauseating and depressing read.

I was convinced that Rooney’s niche ecosystem of young Irish intellectuals would be foreign and educational to me as a newly minted young adult. Rooney’s characters acknowledge their white privilege and are all politically progressive, sometimes even anarchist, in a cutesy way they can get away with. In reality, my experience as a non-white American college student is not that far off. I surround myself with people like me. Sounding smart is easy, but self-knowledge is difficult. It’s the classic condition of a Princeton student, who is so wrapped up in doing well, that she often forgets to be good and kind. I hold the same leftist views as Rooney in an intellectual sense, to the effect of a constant uneasiness in the way things are, but not necessarily a political fervor. Through this lens, I think often about power: white power, black power, the power of men over women, the power of love over me. Rooney explores power too, asking fundamental questions about heterosexuality, monogamy, and age in today’s dating landscape.

Conversations with Friends seems to posit a way of loving, relating, and existing that attempts to break free of the heteronormative conventions of the moment. Other, less psychological, forms of media are trying this too; in the (now canceled) Gossip Girl reboot series, three classmates form a “throuple,” to the disapproval of their parents and intrigue of their peers. This relationship ultimately fails, with two members choosing to stay with one another while the third is effectively abandoned. In the show, polyamory meets a conservative end, proving itself too complicated to last. In Conversations with Friends, Frances and Nick’s extramarital relationship falls apart, until it doesn’t, and the two decide to rekindle their romance in the novel’s final moments, despite Nick’s continued marriage to Melissa and Frances’s undefined romance with her ex-turned-best friend Bobbi.

In Conversations with Friends, dinner table politics are focalized, but not often synthesized. A reader finds themself an inconsequential guest at mealtimes, privy to snatches of meal time debates that Rooney often leaves undigested. These passages appear to stand alone, existing for their own sake as much as to move along the central narrative. The effect is borderline pedagogical. For that reason, I’m tempted to characterize Conversations with Friends as a Marxist novel. While its characters function sympathetically and romantically, a hard and informative edge evokes other Marxist fictions, even philosophies. For instance, Bobbi is the utopian of the group, her pursuit of love, or many loves, reminiscent of Fourier’s The New Amorous World.

In this partial manifesto, Charles Fourier, a utopian socialist of the 18th and 19th centuries, proposes a social order wherein feelings are central to economic development. He identifies the existing relationship between emotions and capital, wherein our innate desires are only acceptable within the constraints of social conformity. In Fourier’s utopia, our careers, relationships, and leisure are determined primarily by our desires. In Rooney and in life, desires delicately navigate rigid economic and social worlds. Wealth disparity and the economization of love comes to light in the novel. Both Bobbi and Nick are generationally wealthy, whereas Frances is poor, her lifestyle unreliably financed by her alcoholic father. When Frances runs out of money to live on, Nick offers her a cash loan, which she takes. The effect is that of a subtle prostitution, although Rooney doesn’t seem overzealous about proving this point; there are many ways in which Frances is using Nick, and they each hold power over the other. While Frances is far from economically driven, she is driven by a desire for security, potentially to remedy the constant uncertainty she faces surrounding her father’s wellbeing. Bobbi seems to prefer more ephemeral dynamics – while Frances writes all of the poetry she and Bobbi perform, Bobbi is the superior reader, with a gift for translating the permanence of words into a meaningful moment in time.

Of all characters in the novel, Bobbi is the most unwaveringly progressive, refusing to allow Frances to call Bobbi her “girlfriend”. When Frances attempts to weaponize her relationship with Bobbi against Nick, Bobbi warns her, “Don’t fucking use me, Frances.” Although Bobbi is quickly characterized as the more vibrant and strong-willed of the two young college students, she frequently displays self-awareness beyond that of Frances, who often chases power over passion. Fourier criticizes the hetero-capitalist world for its treatment of women as “merchandise”. In his writings, gendered power dynamics and monogamy are undivorceable from capitalism, and he proposes an alternative of liberated sexual networks, wherein one’s pleasures are not limited by one’s assets or the nuclear family structure.

How can we love like communists? In the strictest terms, Rooney suggests that we can’t. Far from crafting a polyamorous manifesto, Rooney exposes the fault lines of dating in general, daring us to separate love from economics, security, and self-esteem. In part, the devastation of Conversations with Friends lies in its ability to pinpoint the impurities that taint how we care for one another, without offering a clear or optimistic way out. Conversations with Friends is not so much a guidebook for navigating contemporary love but a state of affairs, even of crisis. The ending of the novel suggests something uncertain on the horizon; Frances is doomed to reprise her fraught relationship with Nick. In an interview with PBS NewsHour, Rooney disclosed that previous endings of the novel were less ambiguous, assigning a definitive outcome for Frances and Nick. That Rooney, who is content to have her first novel considered a love story, saved the ending for last suggests that happy endings, or endings at all, are not focal to Roonian love. Frances’s endometriosis renders her possibly infertile, and although Frances jokes with Nick about having a family together, they both know that their love will never have a nuclear future.

Still, the pursuit of utopian love, or loving for love’s sake, is not a futile one. While Rooney’s ending is explicit in its reverence for the past and disinterest in the future, this lesson can be applied more figuratively. Love that detaches itself from capital and control requires present-mindedness and an appreciation for long-over romances. Our fear of endings makes us crave them; movies are reshot and books rewritten to alleviate the discomfort of ambiguity. Throughout the novel, Frances hurts and bleeds and faints, and yet Conversations with Friends remains a love story. The relationship between Frances and Bobbi, in particular, proposes friendship as paramount, romance as optional, and sex as inevitable. We all love in networks already, be they comprised of friendships, romances, or some blurry other thing. And although we cannot love like communists yet, we can creep towards utopia in subtle ways.

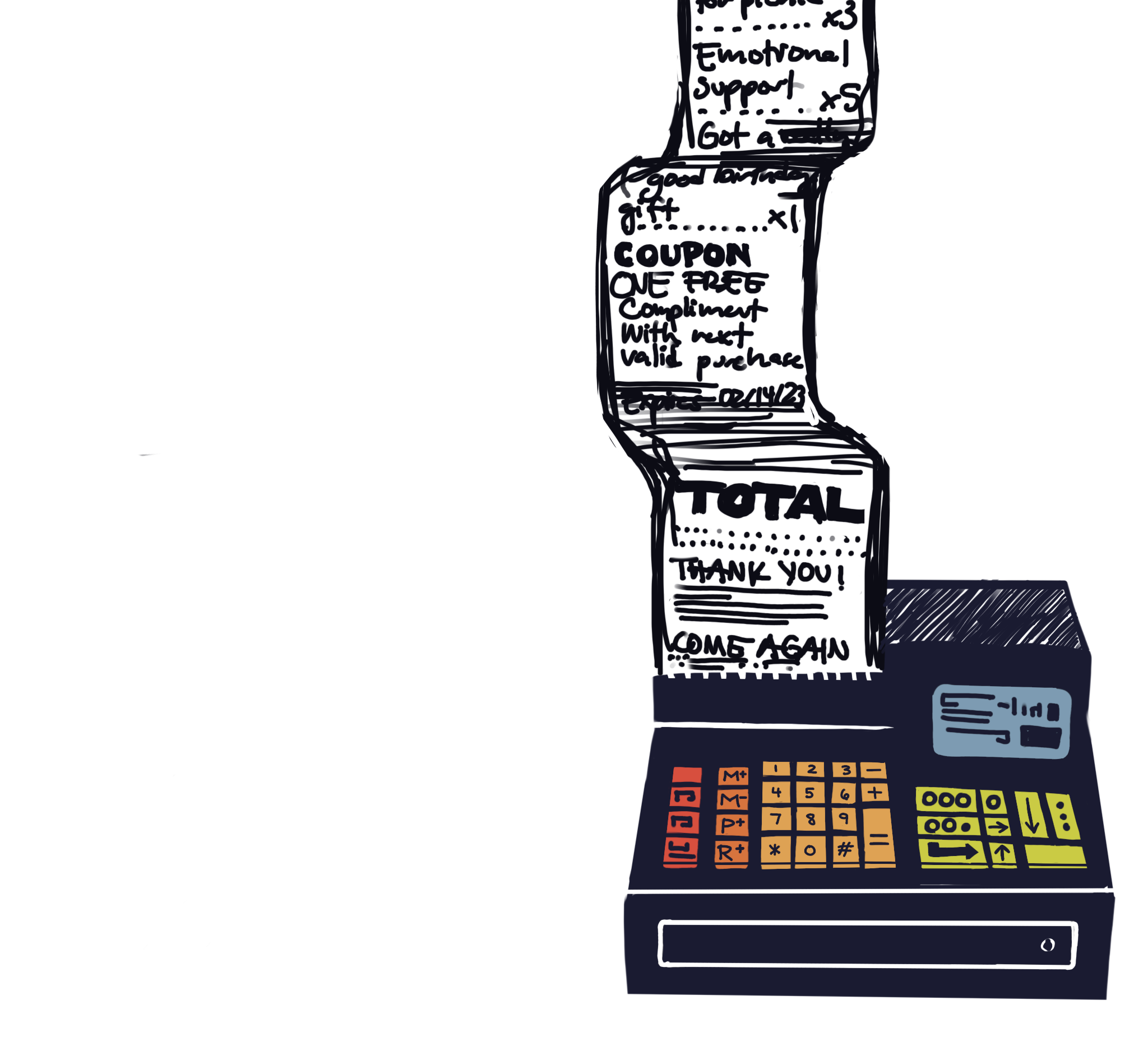

We are commodities in our relationships. The feeling of worthlessness after a heartbreak, the lunches we keep like appointments to preserve tentative friendships; there are countless ways in which we assign and uphold valuations of ourselves and others based on looks, prospects, and other qualities that may one day translate to capital. The way we love now is an alloy, a mix of feelings, obligations, and obstacles. The de-commodification of desire might not cure heartbreak, but perhaps it would soothe us. In embracing the humanity in ourselves and others, we will discover what it’s like to love each other with no ulterior motives: Not as business partners, but as friends.

Leave a Reply