Lots of poetry, etc.., recorded the summer rain (“The chill, uncertain sunlight of those long / childhood hours when you were so afraid”), and then it did the death of late August, (standing “in the disenchanted field / amid the stubble and the stones”), the cracking of the grass, wrinkling of the leaves, the fruit so sweet that its decadence was almost morbid. And now it is early September and hot, hot enough to go to the beach at eleven and go to the shade after an hour, hot enough to find the suspicious witching-green of the mid-Atlantic not far from enticing. No one is around, really, not compared to a day like this just a week ago, in August, when we packed ourselves happily onto the rough sand, when the slightly sticky salt smell of the ocean was kindly adulterated by the poofs of SPF 50 and the coconut-scented tanning oil ubiquitous on the Jersey Shore.

Those attendant scents are strangely missed. Without them, the saltiness of it all is not luxurious but instead smells like the word “brine.” And with that scent wafts the vague feeling that if the water got hold of you, it would pull you out and undertake an astonishing, silent act of violence, throwing you against the rocks and having its rough salt reduce you to a disjointed collection of very white bone, very quickly. Without the associated drama or noise, though; you find you would go rather quietly.

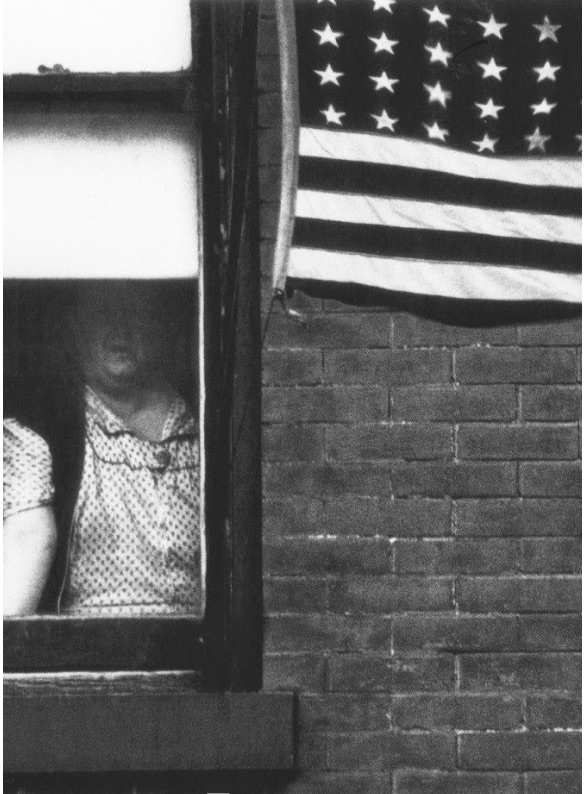

It is September, now, so the beach is closed, but which I mean our job there is done. The shops on the boardwalk are shut, not boarded up, but out of season. There is a certain satisfaction in seeing that Labor Day has once again done its job like clockwork: white dresses, jeans, jackets, put away, straw hats boxed and shelved, crepe shops on the boardwalk covered with their pink and white metal sheets, standing tin shacks in the hot air. Like an old-fashioned, well-established member of the middle class who puts her whites away in September, the shore will not berate you for coming after season, but if she was in your position, she would never dream of doing such a thing. Your presence there is a noted impropriety.

Yes, there is a satisfaction in watching Labor Day do its job well. Like other illusive social structures, it is competent and bustling, year after year. Some will say these structures fatigue just a little, but they have always said so. Mrs. Archer shook her head at their diminishing influence a century ago, when New York ladies started wearing their dresses from Paris as soon as they bought them, despite her injunction that “a lady lay aside her French dresses for one season.” And yet, all these years later, we subscribe to certain descendent iterations of her rule. They are traditions, really, only loose-fitting arrangements that lie quite comfortably on top of the bare elements, knowing fully that what they are doing is not meaningful for any reason other than the order they smilingly impose. Unlike very serious formalities – royalty, aristocracy, bloodlines, which take great offense at any disobedience to conformity – the structures of the shore have a certain self-awareness. They know, as Auden wrote, that “Looking up at the stars, I know quite well / That, for all they care, I can go to hell.” The satisfaction of Labor Day is that it acknowledges the twinkling fiction of order. It acknowledges that chaos must be accepted and subdued with little things like a closed crepe shop or a shelved hat.

Leave a Reply