The only truth is longing, which cannot be exaggerated.

– F. Kafka, Letters to Milena

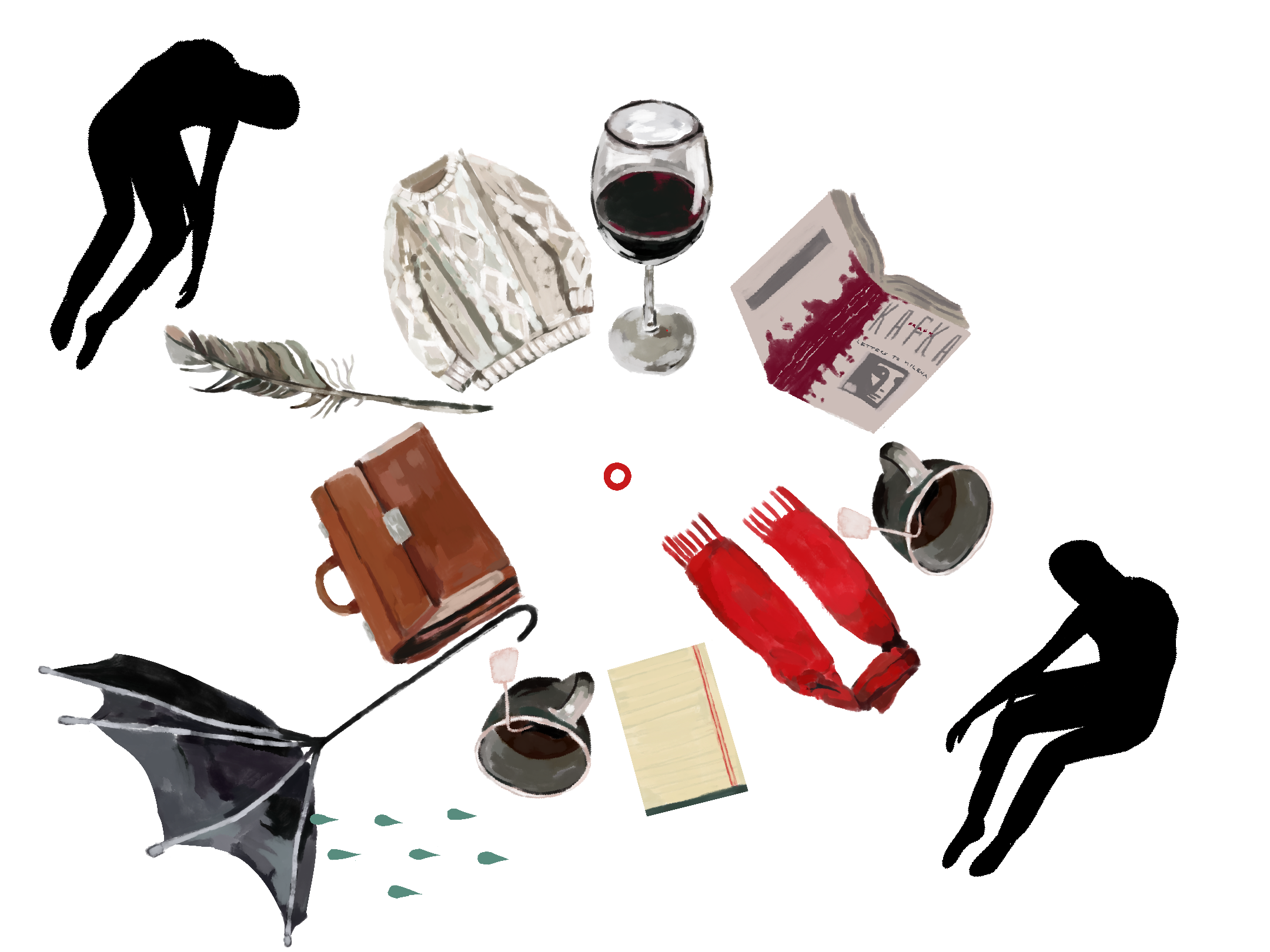

Outside the cafe, the rain is falling sideways and the wind is turning umbrellas inside out. It’s late on a Sunday, the end of early October. On the sidewalk, thick sweaters and scarves sway on bodies rushing past. The city breathes in short, sharp shocks, as if trying to expel us from its lungs. Periodically I hear it roar and shudder.

Inside, everything is angled inward toward an imaginary hearth, negotiating for space that doesn’t exist. The wall is densely decorated with vintage posters and paintings — Caravaggio and his disciples spar endlessly for centrality. Chipped metal chairs and tiny circular tables crowd each other like objects in an unstable orbit.

It is the end of our Indian summer, and everything is in perpetual, violent motion toward the impending Fall. In this space between one thing and another, you can see where reality has stretched too far and stick your fingers through the holes in its fabric. Rain is going sideways. Umbrellas are inside out. Paris is alive in the West Village.

On my table is Kafka, cracked open at the spine. With every word he claws for her: Dear Frau Milena, I am thinking of you always. It is impossible to write of anything else. Dear Frau Milena, I want to hear your voice. Dear Frau Milena, Czech, please.

I want to read you in Czech because, after all, you do belong to that language, because only there can Milena be found in her entirety.

My boyfriend is sitting across from me, staring at his laptop, head in hands — searching for words that sputter in too slowly toward the midnight deadline. I bought the Kafka at the end of September, as a gift for him. Weeks have gone by, and I’ve found the process of personalized annotation to be unexpectedly sluggish. Between September and now — only 100 odd pages, a few hours in Vienna, and some soft pencil marks, sometimes lethargic and sometimes ecstatic.

His rapid typing is shaking the table, the cross of my t stretches frenetically across the page. I erase it and begin again.

IN THE MARGIN: Aren’t we always translating each other?

I am trying to focus, but the moment is too loud to tune out. A teacup topples off the waiter’s tray. Shards of porcelain fly in disparate directions.

To our right, a girl waits with her hands tucked under her legs and her eyes glued to the door. When her friend arrives, the tears are quick and plentiful. The tension disappears from her shoulders like yarn unraveling. Did you break up? The answer is hard to discern, but certainly falls somewhere in between I don’t know and Yes, definitely. I follow the thread. Eventually, a clearer picture emerges: Oliver, her boyfriend, has been feeling off lately. He has been having doubts. They took some space, a week’s worth. Finally, they talked it out, or tried to. They’ll circle back to it on Thursday. For now, she is spinning out.

IN THE MARGIN: Everyone rotates on their own axis.

They were lying on his bed. Don’t worry, they didn’t have sex — but they kissed a couple of times. The whole conversation happened with his arm wrapped around her shoulders, her head resting on his chest.

— Was he crying?

— Yes.

— That’s good.

They order two cups of black tea. Her friend is blunt and at times pessimistic. You probably will break up. He’s going to fuck other girls before Thursday. You think they won’t do it, but they will. Men are just different. Occasionally, she supplements with evidence from her last long-term relationship. I just went through exactly the same shit, she keeps repeating. She thought David was her soulmate. Sometimes — most of the time — she still does. She never thought he would do anything to hurt her. Be more suspicious, she intones. The floor can always fall out from under you.

In front of them is a couple. The woman, who is facing me, is crying quietly. I see only the man’s back, sloped as he leans forward to dab the tears off her face with a napkin, reaching over an elaborate chocolate dessert.

Feeling somewhat like an intruder, I turn toward the window. But the sound of sobs coming from the right remains inescapable.

Why cry in a public place?

IN THE MARGIN: Is she embarrassed by herself? Is he embarrassed by her? Is it possible to be embarrassed while in love, when one sees nothing but the other’s face?

— I know he’ll never find anyone he loves more than me.

— Women won’t leave someone they love. Men will.

At the same time, the friend adds, they’ll probably get back together. It isn’t clear if she’s talking about her friend and Oliver or herself and David. Probably, it’s both. As if they can’t help but play this eternal game of cat and mouse — because that is love, and how could they give that up? I look down at the page. It is precisely as Kafka writes:

You are the knife I turn inside myself, this is love.

— I have never in my life met anyone like Oliver.

— I still feel like David and I will get married.

At last, he closes his computer, finished. He gestures toward the book and smiles knowingly. It occurs to me that this moment, of him catching me in the act, is a better gift than the book ever will be. The words, the stars, the hearts are not the point. The point is my hand holding the pencil, graphite hovering over paper in perpetuity. I could spend forever re-reading, re-writing. It would be enough.

IN THE MARGIN: There is no perfect union, only the endless approach.

On our left is a man — late twenties, I’d imagine — with a formidable leather portfolio filled with beautiful penmanship. He has a red flannel and a red mustache to match. He wields, incredibly, a quill, from which pours an uninterrupted stream of notes. We find the whole thing stunningly analog. When he gets up to use the bathroom, I take a closer look at the stack of books he’s storing on the windowsill. Fancy’s Knell, Ill Wind, Violent Saturday, The Good Old Boys, The Earthquake Man. They all sport the attribution “W.L Hearth.” Neither of us has heard of him. There’s a two-line Wikipedia entry, each point like a pebble swallowed by the sea — American writer, Arkansas, Southern noir, China-Burma-India theater.

I am curious about the notes in the legal pad, about what one could possibly have to say about W.L Hearth and his buried body of work. We joke that that’s what happens when you go to grad school. You go down the rabbit hole, and before you know it, you’re six feet under, communing with the spirit of an author of importance to no one for the rest of your life. On late nights spent looking for him, espresso stains accumulate on yellow paper.

Inside, I’m wondering if that might be what’s happening to all of us. If we aren’t constantly taking pencils to each other’s temples, revisiting scenes, underlining dialogue, circling the point but never reaching it. Again and again, we return to our tables and ready our quills. The curling ends of cursive letters reach toward something that is impossible to grasp. The problem is evident on the page: there is always a space between one thing and another.

IN THE MARGIN: How much of another person can you hold in your hands?

I close-read Kafka close-reading her.

Dear Frau Milena, awake and asleep, dead and alive, you are here somewhere. Dear Frau Milena, it is impossible to miss you, you are here. Dear Frau Milena, you are the sun.

An astronomy professor of mine once described orbital motion as a perpetual fall. Spacetime bends into a bottomless rabbit hole, from which there is no escape. Gravitationally bound to the center, an object will move forever in the periphery unless acted upon by an outside force.

It is Autumn in New York and we are all falling toward the center. The couple gets up to leave, his hand on the small of her back. The girl orders a glass of red wine and buries her head in her hands. The student purses his lips and shakes his head, flipping through the pages. I search for Kafka and I search for him. The rain is growing heavier, but I hear only the constant buzz of cosmic noise, unknowingly hummed under our breath.

I have been singing one single song for you, incessantly; it’s always different and always the same, as rich as a dreamless sleep, boring and exhausting.

We circle in and spin out, imagining the collision. Somewhere on the endless horizon, we see twisted limbs and entangled souls. It is sometimes a dream and sometimes a nightmare. It is heaven; it is a black hole. I feel some eternal truth in the words of the girls next to me — he is evil; he is everything.

Dear Frau Milena, I am coming to Vienna. Dear Frau Milena, I am so afraid. Dear Frau Milena, you are all I have. Dear Frau Milena, I can never come to Vienna.

That’s why I’m not coming — instead of being certain for just 2 days that I have the constant possibility. But please do not describe these 2 days, Milena; that would practically torture me. It’s not necessity yet, only infinite desire.

IN THE MARGIN: Is wanting better than having?

Dripping umbrellas drying off and flushed faces warming up, everyone and everything in orbit; in love with one another and with evil men and dead authors and chocolate cake.

IN THE MARGIN: Is wanting all there is?

The girls, the couple, the grad student, and us.

David, Oliver, W.L Hearth, and Kafka.

Milena, forever.

With red pen, I underline the words infinite desire.

Footnote: This week, the delightful Nell Marcus guides the Nassau Weekly deep into the cavernous expanse of the margins — and there’s no end in sight.

Leave a Reply