Two weeks ago, with light fluttering through the blinds of my windows, deep in the chrysalis of my bed sheets, I had a feeling of deja vu. The moment was reminiscent of many others throughout high school, but one in particular came to mind: in that same lazy state I had watched a video essay, one that asked whether art was “subjective OR objective.” During my bored stint at home, I found myself coming back to the resulting thoughts of that video, and a recent reading that now challenged my old takeaway.

Objective judgment in art is often framed as fascist—it evokes images of Nazis, book-burnings, and an “anti-woke” wave that has pointed itself at POC artists. But rejecting objective “badness” in art makes it more difficult to judge objective worth. Regardless of personal taste, we value something like a Renaissance painting over a toddler’s first sketch. There’s a tendency towards objectivity that inevitably confronts the values attached—giving greater importance to something like the art of the Renaissance painters ends in an overvaluing of white European art and a silencing of its critics. The only solution appears to be a rejection of those objective value judgements, forfeiting the evaluation of art for inclusivity.

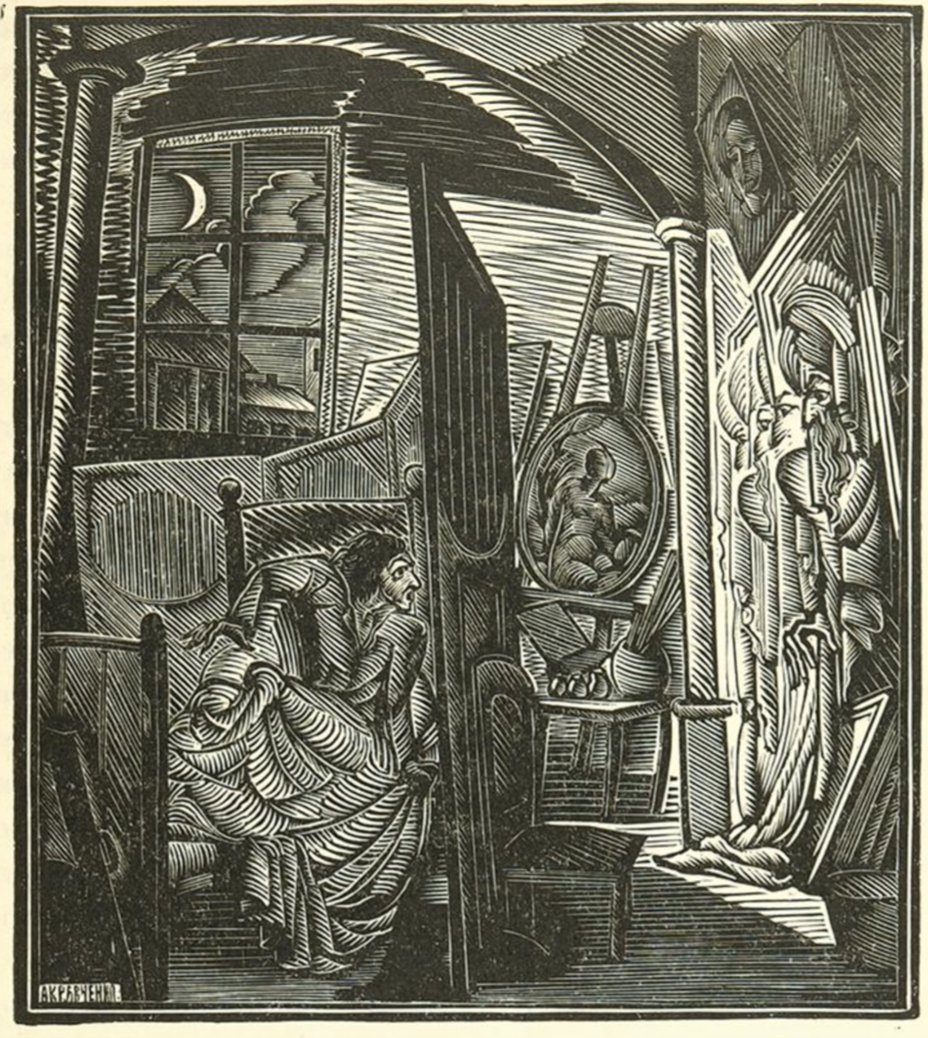

This had been my line-of-thought—one that felt unfinished—until I found Nikolai Gogol’s The Portrait. The short story was written in Saint Petersburg and published in 1835. The Portrait follows a poor artist who steals gold from a ghost, later revealed to be the devil. With the large sum of money, the artist abandons his previous lifestyle of dedication to his craft, and begins to make quick portraits, “in the style of the times,” to keep growing his wealth. Years later, he finds the work of a young painter who, struggling through hardship and study, creates a work that is “pure, faultless, beautiful as a bride.” The narrator sees his own work as a failure to fulfill his potential, and (like most Gogol stories) he goes mad and dies.

This is not a Nass Recommends for Gogol’s short stories (it should be, though). It’s instead a reflection on the morals of the tale. I see two. The first: the devil is out to get you. The second: the artist loses themselves when they shy away from dedication and measured intent.

Gogol’s artist is corrupted when he turns from being “a man selflessly devoted to his work,” into someone who paints for the interests of the upper class, rejecting the “old masters.” What drives Gogol’s painter mad is his interaction with the young artist, in whom he sees everything great he could have done (but failed to). The young painter “immersed himself in work and completely undistracted studies” and, “in the end left himself only the divine Raphael as a teacher.” Gogol’s distinction between the sinful protagonist and the image of what he could have been suggests that the artist’s lofty goal is to put their head down and work tirelessly, with a historical understanding of who has come before them.

This new benchmark provides an alternative for objectivity. Gogol advocated that we do not need to reject value-judgements, but rather understand all art as part of a grander movement; great art is the product of labor and reflection, vision and passion, building off the works that precede it. AI art, and modern art in general, have always come under criticism for being “objectively bad,” or “objectively not art.” “You call that art?” is the common phrase older relatives manage to serve up at every meal. And to be fair, a lot of modern art and AI art feels off. In the world of The Portrait, the narrator’s art gets corrupted because he stops learning from the artists who came before him. This idea holds true for certain modern pieces; the art feels wrong not because there isn’t thought behind it, but because it feels discontinuous with everything that came before it. (Needless to note that this doesn’t apply to all modern art, most is done with serious intent and is only put down for silly or pretentious reasons.) Surrealism managed to schism itself from traditional art because its creators knew what history they were detaching from. But to break away from something requires knowledge of what’s being broken. Otherwise, you do find art that just feels “off.”

This way of seeing objectivity in art seems to resolve, at least partially, the debate over value-judgements. In the case of painting, the Renaissance artists are still worthy of critique, but they also need to be acknowledged as a group to be learned from; making art unlike theirs is a worthy goal, but to do that you have to understand the art you’re separating yourself from. More importantly, Gogol directly connects artistic value to the work put into it. He claims art is a study and craft. It deserves to be judged so that the artists who search for “pure, faultless” beauty can be distinguished. The narrator, upon finding his own failures, wishes he had struggled more, and honed his techniques.

Gogol’s resolution struck me, as someone who’s been finding writing hard recently. A friend recently joked to me that he doesn’t feel that way because he knows he’s only writing for himself, but this isn’t the case. You are here and you have stripped me of that lightness. I want what I do to be able to be judged, but I don’t understand how my writing fits into the world I see and feel. I can intend to write something worthwhile, but if it results in a poor imitation of whoever I’m reading at the time, I have a difficult time finding the point. I’ve tried to understand subjectivity in art to mean that no writing is bad; but if writing can’t be critically judged as bad, it can’t be as good either. Gogol suggests an alternative, where even just my choice to struggle and try means something. It doesn’t make the writing feel any better, but it alleviates my stress to some degree.

Gogol’s message is one where I can continue to judge my own writing, you can judge it, and I can judge yours too. We should judge each other, to keep ourselves on track. It gives value to the struggle that goes into trying to make art (or trying to do whatever work you find important). It’s only from labor and literacy of what precedes you that worthwhile art can come about. I stay in my room and think about trying to write some more. The Portrait’s lesson seems pretty objectively worthwhile.

Leave a Reply