I came across the story by chance; I had coincidentally seen Yelena in the bathroom at Lincoln Center’s Avery Fisher Hall, during intermission. She was anxiously fixing her hair, as I squeezed past women wearing too much Chanel No. 5., and truth be told she did not recognize me at first. It had been eight years since I graduated from Princeton, and for the most part I had cut off contact with most of my classmates. But I could not forget Yelena, whose half-Japanese and half-Russian appearance had intrigued me the first time we ever met. Though surprised, Yelena seemed sincere in asking me how I was, and when I said I was doing well I was not lying.

“How is Eugenia?” I had asked, very naturally.

Perhaps she opened her mouth to lie, but then she faltered. Eugenia was her older sister, and I had met both in creative writing class, six years apart. I was conveniently sandwiched between the two in age — a freshman when Eugenia was a senior, a senior when Yelena was a freshman. Perhaps this degree of both familiarity and distance, combined with her loneliness, was why we ended up skipping the second half of the concert. At the bar nested in Alice Tully Hall, over my whiskey-amaretto cocktail and her decaf (for she already had had a cup earlier that evening), she told me that Eugenia had gone missing.

“Where do I start?” she asked.

“Well, whose story is it?”

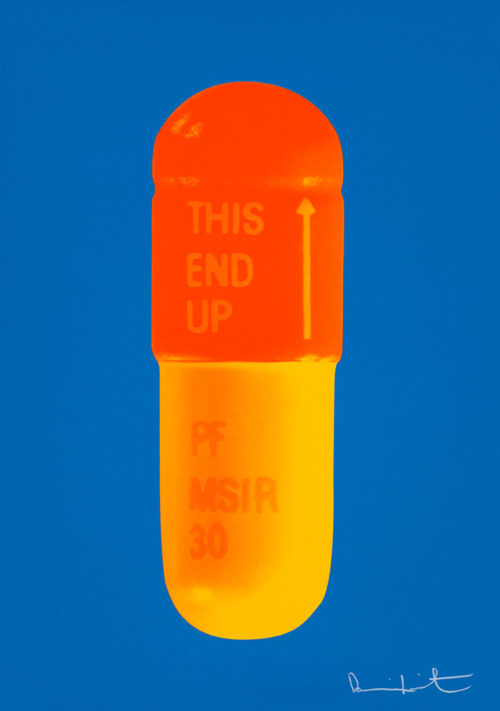

Coffee and painkillers made a formidable woman.

The thought had come to Yelena suddenly, though not unexpectedly — like the opening line of a film, fresh in its clarity and brevity, a line that had the quality of summarizing a scenic montage. For it was early September, and a mindless productivity had taken the city by the hands and danced along as August watched enviously. A camera would’ve followed her down Bowery, catching her at the glass doors of the Italian espresso mart, where she paused to contemplate the sun at six o’clock. Perhaps that, the singular inhale between one car and the next, would be the ripest moment for the opening line.

The problem was that the opening line wasn’t quite true, at least not in the way she wanted. The prescription bottle in her pocket, where the tablets rattled like maracas, or bones, was merely over the counter, taken for the mild headaches she had been getting; and the macchiato in a mug, which she nursed in her hands, had an unceremonious amount of sugar crystals dumped in. She didn’t know what kind of formidable she was groping at, but surely, it meant stronger painkillers for stronger things, and stronger coffee — hot, unapologetically acidic, without any of the milk or additives — something, perhaps, for an agenda without frills.

Her agenda had taken on frills that afternoon—anxiety manifested in detours, winding up and down Manhattan; the A-train, the F, a few blocks over to the 6. There she was, at an espresso mart in Chinatown, listlessly staring at her watch, now edging six-twenty, refusing to open up the book she kept in her bag for moments like these, because anytime now.

But the minutes had continued to tick by.

Fifteen more minutes, and she would’ve waited an hour. So coffee and painkillers made a formidable woman, she repeated as she stood up and left the shop, almost in an attempt to reset the film in her head. She cut across the street the way one was supposed to, confidently and without apology. The cars let out their feeble honks in protest, and she shot them a look that simply dared them to run her over. Truthfully though, they did not care; it didn’t matter to them that the concert was going to begin in an hour, and that before that, she had to figure out where her sister was.

But the fact that they didn’t care didn’t hurt as much as the fact that her sister had promised to meet up beforehand. It was Eugenia’s birthday. Couldn’t she celebrate it, if not for her own sake, then Yelena’s?

“Oh?” I interrupted. “How old is she this year?”

Yelena furrowed her brow as she began counting off the years. “So that’s 30, 31, 32 . . .”

At “…33,” Eugenia had realized that she was counting the pace of her thoughts again and immediately stopped herself. She set down her notepad and took a deep breath. She felt peaceful, even though she had only written two lines; such a morning shouldn’t be ruined by numbers, needn’t be tic-toc’d. But it was a terrible habit of hers, to assign each empty moment a number, and even when she caught herself, inevitably she would resume the counting somewhere, somehow.

She wanted today, especially today, to start out fresh, so that when she would not worry Yelena when they were to meet. She had thought writing would clear her mind.

Life is the fiction you choose to live.

The handwriting was even throughout, no indication of whether she pressed down harder on life or fiction. Either way, one could not exist without the other, at least for her. It had taken her 33 thought-paces to come to that conclusion, but it was one that offered little reprieve. What if she had continued counting? Would her thoughts have led her to the missing link to her current novel?

Unlikely.

She didn’t know why she simply couldn’t let her current novel go, to let her characters just live forever in the realm of abandoned stories. No, in fact, she wouldn’t even be abandoning them. She would be doing them a favor, of letting them retire gracefully before they died from being overworked and rewritten and given new motives. There were some stories that were written simply just to be written, not published or dissected or contemplated over too many coffees and wines. But this one, no matter how much reality demanded that it be put to rest, lived on persistently. Eugenia was physically unable to begin a new narrative, not as long as this one remained so unfinished in her head. Because this was so pure, so desperately pure, and she wasn’t. It hurt her to be the author of such a world. Something wasn’t enough, she wasn’t enough, and the days were just going to pass and the sentences were going to run on and on and on . . . but this story could save her.

It was affecting her life — her real one — so much that her family was no longer dismissing her obsession as part of her peculiar, writerly disposition, always too caught up in something she seemed to have just missed. That’s how it often felt: something was always escaping. If only . . . if only she could transcend the physical qualities of creation.

Alright, she decided. The problem was that she was simply too clouded at the moment. So much life was going on in her that it was hard for her to discern her life thoughts from her fiction thoughts, the ones that would strike at the heart of a story. If she could be nothing, if she were able to be suspended in Pure Nothingness, a room with nothing, and then taking the room away, what exactly would she find?

Would she still hear her own heartbeat, or the susurrations of her blood, like the faint rustling of soft sand and rainwater? And if she were to twirl en pointe, would she be able to tell that she were moving? Would she reach out a hand and play with the fabric of the universe?

No. Tonight, she would put all of that aside, for she had a concert to go to, with Yelena, her dear, dear sister. She had hurt her for too long, so she should stay put here, if only for tonight. They had promised to meet downtown. Oh, dear. Looking at the clock, she realized that she had missed their appointment. Was Yelena angry?

She sat there, unmoving, letting the guilt inside fester and eat up what was left of her. Then, she got up to pause the music, because although she didn’t know where she was going or if she was coming back, it wouldn’t do to keep the stereo going while she was gone.

The silence that followed after the front door shut seemed to suspend itself in the room, and it was this same sort of silence that filled the air when Yelena emerged from the subway, the wind quietly settling about her.

When Eugenia did not answer the door, Yelena, for a reason that she could not wholly grasp, knew where the spare keys were hidden. With delicate fingers, she had pried open the buds of one of the imitation roses by the door, and there it was, nestled in a bed of yellow, plastic stamen, the keys to her apartment on the seventh floor. It was surprising that they existed in the first place, for Eugenia was not the kind to believe in backup plans.

A gradient of light extended from the entryway, cast in shadows, across the living room, to the windows, where the chiffon curtains framed a glass wall overlooking the backside of Lincoln Square. The room was inviting, looking both clean and lived in, but vaguely so, like someone had learned to get to the heart of something while still remaining on the periphery, to live without existing.

This struck something in her, made her hurt for what she could not be for her sister. It always seemed to her that Eugenia was always stuck in her own head, prone to action patterns seemingly triggered by things that only made sense to her. And they let this happen because Eugenia was brilliant, brilliant in a way that suggested a personal brand of logic to which no one else was privy. When she was in primary school, Yelena had taken it upon herself to find her elder sister at the junior high division down the street so they could walk home together, never the other way around.

It was hard to imagine they had once been small enough that age made them so different. Their history traced from Moscow to Japan to Manhattan, transnational anecdotes in their mother’s soft voice, the past a fairytale meant to explain who they were, why they were, and how they had come to be. Eugenia, a portrait of placidity, peering up at butterflies, while Yelena would try to catch them with nets that billowed above them like kites. Oh, the simple novelty of memory, of those watercolored days.

But always they tried to be there for each other, no matter how twisted the understanding between them had become over the years. They hadn’t factored in the depressive episodes, the withdrawals into New York, where it was so easy to hide behind the glittering façade of possibility—because if everything had a chance of happening, then nothing was going to—just like being published or being happy or just being. Who started taking prescription pills first, and for what reasons, who had forgotten Russian first, who had stopped using their Japanese names — all these questions without the question marks had formed the emotional backdrops into which the butterflies of their childhood had flown and fallen. The more Eugenia seemed to get frustratingly lost in her mind, the more Yelena was determined to stay rooted. She called, checked in, always provided a narrative framework on which Eugenia imposed her internal monologues.

She did not know why she was remembering this, in the hallway of her sister’s empty apartment. She slipped off her canvas flats and peered into the shoe-rack for house slippers, noting how all the shoes were in place. Tentatively, she walked into the light pooled in the living room, where an impressive stereo system sat. A little green light was on, the giant speakers warm against Yelena’s palm, alive, withholding a quiet pulse underneath its wooden panels. It wouldn’t do to leave the stereo on. Shaking her head, she reached to turn it off.

The light turned red, blinked twice, and went black. Almost immediately, the sleepiness hanging in the room, the one she hadn’t realized was there, dissipated, like the flush of a suspended cymbal, waiting. The room was incredibly quiet, and almost as though to compensate, a pigeon outside the window cooed.

Yelena peered around once more; there was nothing more here, and besides, the concert was going to begin soon. They would meet directly at the hall, no doubt. She trusted Eugenia.

Seven forty-five.

It had taken her an hour on the Q-train to get to the ocean, and now that Eugenia saw the horizon, tinged with what was left of the sun, she knew there was no way she was going to make the concert, or any concert anymore, for that matter. Her arrival had been gentle, the wooden boardwalk on which she landed soft beneath her bare feet. The water, whose small waves sounded like hushes, seemed to promise a world without counting, and Eugenia hurried toward toward the shore. It felt very much like beginning a new story, where the important part was to just write and write and to worry about the rest later. How freeing it was! As she frolicked in the water, she wondered who she would delegate the responsibility of editing this story to.

What a shame it was, then, that she couldn’t have waited one more day. She hadn’t meant to let Yelena down. And the concert that night . . . they were playing a piece that she especially liked . . . but what was it?

She frowned. The name, and the water, had completely slipped her head. Before she could ponder further, something sounded in the distance.

“The bells,” she whispered.

“The bells,” Yelena said, “of Moscow.”

They tolled gently, the famous opening chords of Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto 2. Each one grew progressively louder, the entire sequence being pulled apart by harmonic tension, pulled back together with the common bass note of F — she did not have the words for it all, but because she knew this piece by heart, she didn’t need any. The piano had unfolded so naturally, so effortlessly offering itself up to the symphony orchestra, it felt to Yelena a sacrifice—a life for a life. How curious it was, that in the opening movement itself, the piano had chosen to play accompaniment to the strings.

She didn’t know why she had come, especially since the seat next to hers was empty. The concert had begun, and there she was handling the pain of Rachmaninoff alone. Again, there she was, trying to create the semblance of life for the both of them. But she trusted Eugenia, and even if she were late, she had to believe that she would come. Perhaps, because it wouldn’t do to enter during a performance, she was there now — listening to the concerto right outside the hall.

The concertgoers were leaving by the time Yelena finished her story, her decaf untouched. My cocktail, on the other hand, was all gone, as with my words. This wasn’t what I had in mind when I bought the tickets to this concert a few months ago, yet it didn’t seem all that strange that this unexpected turn of events had happened. I was the one who had sought out Yelena, when our paths had crossed in the bathroom, and I was the one who had asked about Eugenia. If I had not done any of that, I would not have gotten the story.

“What are you going to do now?” I couldn’t help but wonder.

Yelena buried her face in her hands and sighed. “Call our mother, I guess. Or should I wait another day? I can’t just tell the police that Eugenia’s missing on the basis of sister telepathy, or something.”

“No,” I agreed. “That’s the stuff of fiction.”

But fiction is the life you choose to tell. Happy, happy birthday, Eugenia.

Leave a Reply