I like to think that human dignity is a fundamental right that must be protected and preserved. This take isn’t original. It’s one of those things that I’ve learned over the years and that has never left me. Regardless of what my family was going through, my parents insisted on keeping a brave face. This is a face whose aim is not to mask our suffering; on the contrary, it is one that reaffirms our refusal to be seen and treated as any lesser than human beings. Even in the face of adversity, the people in my life always kept their pride. When they asked for help, they did so with their heads held high, determined not to let harsh life conditions take precedence over their self-esteem. I see dignity as one of the core symbols of our humanity, and, to me, losing it means giving up part of what makes us human. I was always told that one cannot lose their dignity unless they allow it. This loss doesn’t happen overnight. It comes from compromising on values that make us who we are and belittling ourselves in front of others. I see this self-destructive process as a disease. It is one that gnaws at you and disturbs you slowly. A tumor that conquers the fundamental intangible part of yourself, until you finally diagnose yourself with cancer. And as with all cancer, few will recover that part of themselves that has crumbled away. This is how our dignity fades away when we allow it to slip through our fingers.

So, I thought you could only lose your dignity once, until recently.

For several days now, I had been following the development of the situation on the American-Mexican border in Texas. I won’t describe it as a crisis. Crisis, a word overused by mainly western media to describe political movements, has lost most of its meaning and the sense of urgency it once suggested. This border problem is only an aberrant symptom which reflects a much deeper evil: American imperialism. It is a cancer that has been harming the Haitian people for a while now. I will spare you a history lesson since a tale of the thousand and one ways that the United States has fucked Haiti over the years is pointless. It is, after all, a ditty whose rhythm Americans know too well. Instead, I will return to human dignity and how I discovered last week that it could be lost more than once.

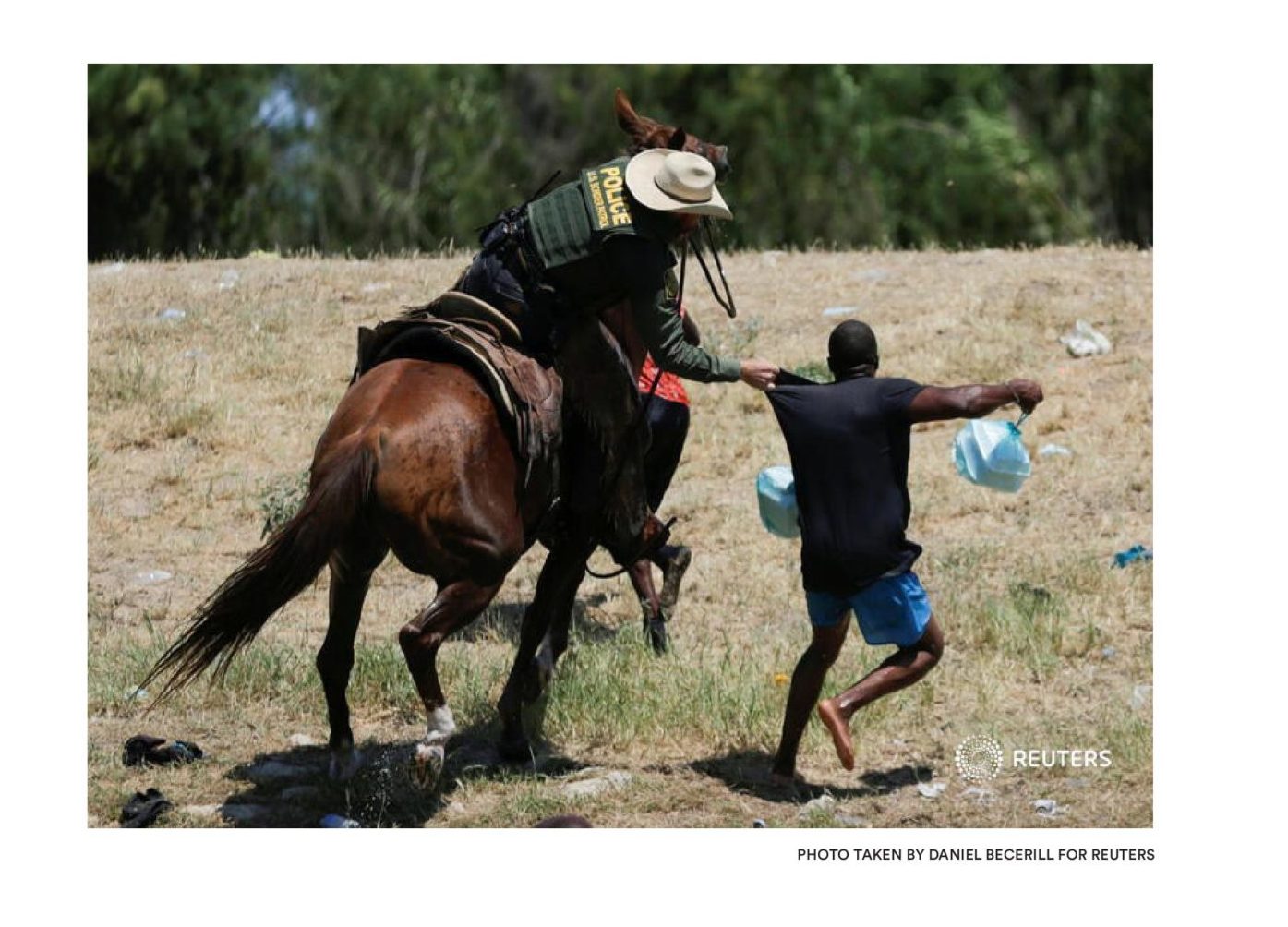

This past Monday, I was having dinner alone at WuCox after a hectic day. And like every time I dine alone, I took advantage of my solitude to scroll through my Instagram feed and thus, to some extent, update myself on the news. Suddenly, I came across a photograph that disturbed me. On one side was a white man in uniform mounted on horseback and wearing a cowboy hat. On the other was a black man with a fanny pack wrapped around his neck and a pair of blue plastic bags in his left hand. The man on horseback, his face tight, was pulling the shirt of the black man who seemed to be frantically trying to escape the grip of his tormenter. Between the two, a whip was swinging, epically representing the stark opposition and abusive power imbalance between both men.

This image undeniably evokes slavery. The reference is so blatant that, in black and white, one could easily think of the photograph as a manufactured illustration of slavery in the 1700s, particularly a representation of the dynamics of power and the relations of violence between the slaveowner and the slave. This photo, however, is far from being manufactured. It’s very real, and the scene it captured is even more so.

I was appalled. Horror and shock, however, were not the only emotions that I felt. In fact, I had succumbed to the grip of a whole amalgam of feelings: anger, frustration, dismay, disgust, sadness and desolation. They all simultaneously took hold of me, leaving me confused about why I was suddenly feeling out of touch. I looked at the photo for a long time, well beyond the ten seconds that were necessary for me to see and understand it. I already knew that the white man was a border patrol agent who was trying to prevent a Haitian refugee from crossing the Mexican-American border, around the Rio Grande. At that point, I was staring at the picture not to understand but to feel my emotions take shape within me, and gradually take hold of me. I felt them to the point that they were no longer distinct from one another, and I became numb to their particular effects. Perfectly present and absent at the same time, I stared at the photograph and felt myself losing shape.

It took me a long time to understand my reaction. Yes, the picture was shocking. But it alone couldn’t have unsettled me so much. I was already aware of the problem at the border. There had to be something else. When in the evening I took the time to contemplate my internal state, I understood why this image had disoriented me. It had put into question a notion that I had held inside me since childhood: that human dignity could only be lost once. The photograph was proof that I was wrong.

Surely, the black Haitian man had already given up his dignity to undertake a grueling journey, fleeing his home to throw himself at the mercy of the generosity of people he probably hated with all his soul. He leaves behind the place he loves and the people he cares about to go somewhere he knows he is unwanted and looked down upon. He trades respect and the feeling of belonging for mere survival. The deal does not seem fair but he agrees to its terms anyways. He feels like he never really had a choice.

La mort lui tend la main. Il la rejoint pour une dangereuse valse. Ils dansent tous les deux au-delà du crépuscule, bravant ensemble les dangers de la piste: la déshydratation, la famine, la séquestration, le viol et ironiquement, la mort elle-même. Son partenaire.

To embark on such an adventure, where the journey itself is symbolically and physically degrading, one must have already involuntarily sacrificed their human dignity. This photograph shows a man who had already sacrificed his dignity being robbed of it once again. To have something that you had already given up stolen away from you is a fascinating paradox. If only the man had crossed the border, he would have been stripped of his dignity just once. Since he had been intercepted; since he was pulled by his neck like a dog that needs to be leashed; since his involuntary peril had served him for nothing; since he was going to be put on a plane to Haiti, him and his family; since he had to step foot on the soil he had sworn he would never come back to; since he had to go back to square one, coexist with corruption, incompetence, poverty, hunger and armed gangs; since he had failed, he had to lose his dignity a second time. If the first time he had given it up, this time it was taken away from him.

The officer on horseback, meanwhile, charged the migrant probably thinking he was only doing his job. Yet, he failed to realize he was dealing with a human being. He had learned that empathy was superfluous in the performance of his job. He was not paid to sympathize with these dirty immigrants. Therefore, he could never have seen the Haitian man as a human being with a history, dreams and aspirations. He had been trained to see him simply as the object of his violence.

Yet, the Haitian man was not only an immigrant. He was above all a man. Perhaps, he was a father, who, in the span of one year had to face a devastating earthquake (the second in eleven years), yet another disastrous cyclone, the assassination of his President and the violence of armed gangs. Yet, he was still denied the right to find refuge in a world which he was convinced belonged to him as much as it did to the white man who was abusing him. This is a man who was betrayed and denied everything to which he already believed he was no longer entitled.

It hurts to see someone lose what they had already given up.

Leave a Reply