When you wake up in the morning and see frost on the windows that’s thicker than the panes of glass themselves, you don’t have to look outside to know that the river is completely frozen through. It cuts through the middle of the city, and when the sun finds a way to peek through the thick layers of clouds hovering a few feet above our heads, the entire thing shimmers. People are wrapped in thick downy coats as they pull themselves over the waist-high iron fence and practically roll down to the river’s edge; they’re splotches of bright red and blue with fur hoods as they tromp over the pale silver and pitch tents. They will be ice fishing by afternoon, for weeks on end. I’ve never stopped to ask why.

We are all wrapped in thick downy coats when we make our way outside. Don’t smile at the person in the corner of the elevator when you step in—turn around, press the button of the floor you need, and wait. Once, after spending some time away, American-trained reflexes pulled up the corners of my mouth into a passive greeting before the shock on the stranger’s face reminded me where I was. How funny that in a place where rivers freeze over and clouds hang onto your shoulders, fake sincerity is what strikes me as cold.

It’s hard to see each other’s faces past the coats, woolen scarves wrapped from ear to ear to mouth to throat, hats pulled down to cover our eyebrows. We catch the puffs of frozen air and their eyes, their side-eyed glimpses. We walk down one of the main streets just next to our old apartment. It’s lined with small shops: Adidas, a tracksuit-sporting Eastern-European favorite, and Talisman, stuffed to the brim with hand-carved wooden Kazakh trinkets and little spindly camels woven out of string and wire. I love the jewelry—every day I wear something handmade from home, with swirls dug into the metal that I can trace with my fingers while I count the days until I can go back.

I’m walking down one of the main streets with my grandfather, and our faces may be closed off from the cold, but we can still catch each other’s eyes. A peek of the dark, weathered flesh of my grandfather’s cheek is an irreplaceable backdrop for his shining eyes that crinkle up when he laughs. His eyes are dark brown and shaped like almonds. Mine are blue and rounder than the knobs at the tip of the posts of the iron gates people jump over. Sometimes a strand of blond hair peeks through my hat, and it waves in the wind.

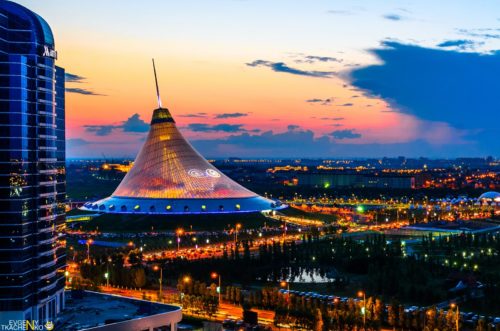

“No, you don’t look like you’re from here at all.” He takes a puff of hookah and exhales through both nostrils, narrowing his eyes and glancing appraisingly at my big nose, pale skin, wide eyes, messy hair and clearly foreign-bought blouse. His cheekbones cut sharply across his face; he sinks back into the gleaming velvet seat and takes another puff. I don’t think a bar named “Mister Coffee” would do so well back in the States, but on a faded street corner at midnight in Astana, every table is full and every waiter is calmly replacing coals and pouring glowing cocktails. I shrug and run my fingers around the stem of my glass. I choose not to say anything.

What could I say? “I know?” How painfully obvious. I run after my baby cousins down the hall in my house in New Jersey, all three of us are giggling, even though we all know that I will catch them eventually. They’ve just moved to the U.S. a few months ago. Both are starting to drop English words into their adorable Russian baby babbling—I remember my parents telling me how I did that, too. I swing Isanna up and rest her against my shoulder, and she nuzzles her head into my neck as I hum and bounce her side to side. I wonder how many years it will be until she asks her mom why Aunt Liza looks so different. I place her down and watch her wave one little tan hand over her grinning mouth and shriek with laughter and she runs away, dark eyes flashing a challenge at me to catch her again.

My grandfather used to take me to ride my scooter around the river—in the summer, when the waters glinted dark blue and concerts were held right next to the water’s edge. One time I fell off and scraped my knee. He didn’t let me cry—he picked me up, put me back on, and watched with guarded eyes as I gave it another shot. The people around us were confused. They used to ask him why he was babysitting a little Russian girl, and when he said, “She’s my granddaughter,” they’d laugh. I can’t tell you how many years I spent wishing I had the hair color and bone structure of the man I respect so much—the one who taught me to get back on the scooter and ride.

We go back home and unwrap ourselves from our cocoons, laughing as we stomp snow onto the mats before being shooed away to get ready for dinner. In Kazakhstan, red tablecloths are spread with endless bowls of salads and platters of dried meat, fish, and pickles; we drink carbonated water, ask someone to pass the gelatined pork (holodets), and spear pieces of herring mixed with mayonnaise and beets into grinning mouths. We will not leave this table for hours—and we will laugh so hard at my uncle’s dirty jokes, his wife’s shocked gasps, and my dad’s witty retorts that we won’t even notice the lights draped around the bridge outside turn on, or the stars twinkling from the clouds that have chosen to give us the moon that night. I stop by the kitchen to help my grandmother with the main course: beshparmack, horse meat and boiled noodles. While we’re grabbing forks and moving the food onto a serving dish, she absentmindedly fusses with my hair and looks up at me with my eyes—big, round, and blue (although she likes to argue that they’re green). Later that evening, after we clear up plates and break out the teaspoons, tea, and candy, breaking into small conversations and contended silences, I make eye contact with my dad and smile. Whenever he sneezes, he sneezes twice, and I only ever sneeze once, but we have the same nose, and when I was little, he spent hours teaching me how to draw and how to sew. I rest my head on my mom’s shoulder and squeeze her hand. She squeezes back. She left this place so my brother and I would speak English without accents—but I am forever grateful that my Russian continues to sound like hers as well.

I don’t know what I wanted when I was little. I don’t know if I wanted to look like my stunning mother with her beautifully sloping cheekbones, or my dad, with his beaming smile and crinkling eyes. I don’t know if I wanted to look like my brother, who is separated from me not only by age but also by the incredible variation in our looks. And I really don’t know if I wanted to look like my grandfather, a steadfast Kazakh man. I suppose that all I wanted was to walk down one of our streets in the summer to buy fruit from local vendors without quizzical looks and questions about where I’m from. I’m from here—why can’t you tell?

But I cannot forget those fruit vendors, just as I cannot forget those brightly colored coats on the ice in the winter and the smells of sizzling meat in dimly-lit restaurants, cigarette smoke clinging to my hair and my dresses when I came back in from late nights out, the crook of our comfortable couch with a painting I made when I was twelve years old hanging above it. The sunny walks, being forced to do math by my grandparents in our old apartment, running to the grocery store to swim in the pool on the floor above and making my brother buy me pizza after. I am a product of this place—this incredibly unique, complicated place that has become a series of snapshots, feelings, and memories in my mind. Some years ago, a Kazakh man married a Russian woman, and they had my mother. She married my father, and I was born. I do not look like any of them—not Russian, Kazakh, or Jewish. Instead, I look like them all. I am forever a part of this corner of the world—how could I not be, when it is the reason that I get those strange looks and questions to begin with? It is mine, whatever ethnic mutt I may be.

I haven’t been back in a year. When I go back, I will go to that hookah bar again and probably meet someone new, another person to shake my hand and ask me what it is I’m doing there exactly, especially with the American ID I will use to get in. And I will just trace the stem of my glass again, and smile, and say nothing.

Leave a Reply