The hotel phone first rang at 12:30 in the morning, but when I picked up, the line was silent. I thought I saw a light flashing between the gaps in the curtains of my room. My room was on the first floor of an open courtyard in the mountain town of Manali, perched in between two valleys of Himachal Pradesh in the Indian Himalayas and split by the tumultuous Beas river, cold and gray in July. Outside, I could hear men talking. The walls were thin, but I tuned it out; it takes focused effort for me to understand any Hindi anyway, so I let their chatter fade into the nighttime chorus of barking dogs, monsoon rain and creaking walls.

I arrived in Manali earlier that afternoon, after a draining twenty-hour bus ride from the arid region of Ladakh higher up in the mountains. We had driven all through the night on unfinished, unlit roads that wound their way through treacherous passes and police checkpoints where I groggily presented my passport, my visa and my sleepy face to increasingly unfriendly police officers as the night wore on. Every time I came close to sleep, I was jostled awake by a bump in the road or a turn so sharp I slipped off my seat. I had —unwittingly— agreed to serve as co-pilot of the 12-seater minivan, which, though it entailed no driving (which, as a city-dwelling millennial whose driving experience is limited to golf carts on Cape Cod, I couldn’t have presumed to do anyway), meant that I couldn’t sleep; I had to keep the driver awake through idle conversation and Bollywood tunes. By the time we arrived in Manali in the late afternoon, I was so sleep-deprived that I wandered the streets in a quasi-delirium, looking for a place that was cheap and would take me in for the night, totally undiscriminating otherwise.

Pine View Hotel fit the bill. Though I could see no pines from my first floor room, and doubted that the three-story building nestled deep into the city could reach above the other buildings, the 500-rupee room with private bathroom won my heart. The receptionist, a portly man who introduced himself as Lucky-ji, showed me around the sixty-square-foot room with great pride.

“The water,” he chanted, “is hot, twenty-four seven, twenty-four seven! Solar panels, madam-ji.”

I tossed off my rucksack and thanked him, paid the fee and— for what felt like the twentieth time today— signed my passport information, my visa number, and mustered a smile. Lucky-ji shook my hand and pulled me into a hug.

“Any problem,” he said, “you tell me.”

***

Shortly after the phone rang in the night, sometime around 12:45 in the morning, someone knocked on the door.

“Madam?” came an unfamiliar voice.

“Kya? Kya hua?” What? What happened?

“Bottle water, madam-ji.”

“What? I don’t want water. I’m sleeping,” I answered from my bed.

“Water, madam-ji.”

“Nahi, nahi, I am sleeping.”

“You don’t want water, madam-ji?”

“Nahi.”

“Maybe tomorrow?”

“Shayed.” Maybe.

“You didn’t ask for water, madam-ji?”

“Nahi.”

“Wrong room, madam, sorry.”

I rolled over, still in bed. Men outside my window were laughing. They spoke too fast for me to understand, but one of them was clearly drunk; I heard him slurring the words to a song and either he was dancing or slipping on the few steps outside. The rhythm of his feet seemed uncertain. The tone of their voices escalated; they were laughing too loud now. An older-sounding voice tried to pull the drunk one away from the hotel courtyard and its sleeping guests. The drunk man yelled, “phone dekh!” – show me the phone. They fought for a while, their voices growing louder and then distant.

***

At 1:06 AM, the phone in my room rang again. It stopped before I could answer. I hadn’t gone back to sleep, frightened by the flickering lights that filtered through the gap in my curtains, by the men who I could hear walking outside my window. In the dark, I imagined the worst, as one is prone to do when female, abroad, and alone. I had locked the door from the inside, and had checked on all the windows. But this was India; taking a door off its hinges probably wouldn’t be that hard.

Then came another knock. I lay in bed, silent, terrified.

“Madam?”

I didn’t answer.

“Madam?” the voice persisted.

“Kya? Kya chahiay?” What do you want? I tried to sound bold, confident. I was scared shitless.

“Please, madam. Let me in.”

“Kyon?!” Why?!

“Please, madam,” the voice whined.

“Nahi! Jao, jao!” Go, go! I was shrieking now. I ran through my options in my head; of course, there was no Wi-Fi, I had no phone service, and I didn’t even know the police’s number. Rousing the other guests with my shouts seemed viable, though not ideal. Lucky-ji said there was hot water; was it boiling? Maybe I could fill up a bucket and throw it at the voice if it breached the walls, Middle-Ages style. Based on my shower, though, and given it was the middle of the night, I guessed the water would be lukewarm at best. I looked at the phone to see if there was a number listed for the reception. The only number I had on me was on the front of a postcard, for the tourism office in Leh, over 400km away and definitely closed at 2AM.

“Pleeeeeeeeeeease, madam,” the voice continued, offering no explanation either in Hindi or in English why it wanted to be let into my hotel room in the middle of the night, which in itself I took as an explanation. I was nearly crying now. I said no, no, no. Bas. Enough. Mat karo. Stop.

I kept my voice steady. I yelled so loud that I’m sure other people must’ve heard me. The courtyard was empty of sound, except for the rain.

It crossed my mind for a minute that maybe he just wanted shelter from the monsoon.

It also crossed my mind to open the curtains and see if I could frighten him off; at 5’7″, I am typically taller than most men here and tower over nearly every woman. I ruled that out; I worried that showing myself might entice him— not that, in my purple elephant-print pants and oversize green TI shirt, I was a sight to behold, but simply that any response would be taken as encouragement. I didn’t understand what he wanted.

I wanted my sister. I wanted my mom. I tried to dial their overseas number on the hotel phone, to no avail.

It had been a few minutes since the voice had last implored to be let in. Now, he was throwing stones against the wall of the room. The walls were so thin— so thin I thought I could hear him breathing— and I was sure he would break them in no time.

***

I write this in past tense because it is easier to deal with this way. It sounds like I have a solution, like I am reaching a conclusion. I don’t have a solution, there is no conclusion: this is happening to me right now. There is a man outside trying to break into my room at 2:45 AM. He has been at it for nearly three hours.

I don’t know anyone at all in the vicinity of literally 400 kilometers. I have turned the lights on. I don’t think I’m going to sleep, though I’ve barely closed my eyes in the past two days.

I will stay awake until morning— when women are milling about outside, when Lucky-ji is back and I can complain in a strongly-worded speech about the water that is decisively not hot “twenty-four seven”, when I can run to an internet café and feel closer to the people I know and love. Until then, I will write.

***

The phone rings again at 3:23 AM. I let it ring, once, twice. I answer. Nothing.

It rings again. Kaun hai? Who is it? I ask. As if I don’t know.

The voice whispers something. I can’t understand it. I hang up.

It rings again. The voice is breathing, loudly.

It rings again. I unplug it.

***

It occurs to me that the man is probably throwing stones at the windows, not the walls, and those are much more likely to break. But it is 4:02AM now and he’s had no success so far and in fact I don’t think I’ve heard him do anything in a little while so maybe he’s given up?

4:06 AM: Nope, still there!

4:12 AM: It sounds like he’s scratching the door right now, unless it’s a dog. I also thought he was slipping a note under the door earlier but I didn’t see anything, and then I thought maybe he was lighting a fire and trying to smoke me out, but I now remember it’s monsooning outside and I doubt he would be successful.

4:17 AM: I really think he’s trying to unscrew the hinges.

***

I am so tired. I think he hears it in my voice, when he knocks again and I say “jao, jao, jao, jao, jao.” Go, go, go, go, go. I am not screaming anymore. I wonder what will happen when daylight breaks.

***

New plan: next time I hear him outside, I will shout and shout and shout. One long, uninterrupted cry. Aaaaaaaah. AAAAAAAAAAAAAAH. I will wake everyone up. I will pull back the curtains, confront him with my bulging, blood-shot eyes, and just SCREAM. Now that the phone isn’t ringing anymore, I am much more angry than I am scared.

***

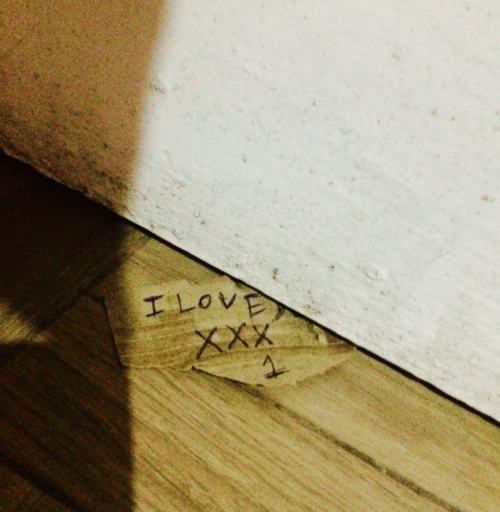

I was wrong. The man did leave a note under my door. It reads, “I love you xxx 1.”

***

I am in mourning for all my lost sleep. I am headed to Chandigarh in the evening, and I have no place to go (to sleep) in Manali until then. The next occasion I have to look forward to is in a 10-hour-long overnight bus ride, head lolling on strangers’ shoulders as we wind further down the Himalayas, legs crumpled under the seat in front of me.

I am so deeply, existentially, powerfully angry that some strange man’s twisted notion of affection for someone he, in all likelihood, glimpsed in the street or through the slit in a curtain, could cause so much fear and unrest. This balance of power is so profoundly unfair, so completely perverse.

This isn’t cute. This isn’t romantic. This isn’t a love letter. This is harassment. This is criminal.

I am still scared of leaving the room. It is 5:34 AM and I haven’t slept for a minute. I don’t know if my response to this man’s behavior was the most effective— was yelling a form of goading? Did keeping my light on all night suggest I was soliciting his advances? Does it matter? This is happening to me because I am a woman, and because I am alone. The fact that I have to know this shit— that I have to acknowledge that my safety can be compromised at any time and that I need to have the mental acuity, strength, resources and energy to combat this— is not tolerable.

When I tell Lucky-ji in the morning, will he empathize? If I go to the police, will they understand? My guess: as a white foreigner, I might get better treatment than most. But I am familiar with the workings of the police in India— two years ago, I translated 100 instances of police misdemeanors and collaborations in cases of sexual harassment, rape and human trafficking in the state of Uttar Pradesh— and the reaction to something as mild as this, as seemingly inconsequential, “a love letter!”, is unlikely to be in my favor. Maybe if I’d gotten a picture of the man. Maybe if I’d recorded the act. To be honest, I am so scared to leave my bed I haven’t even peed all night. I wasn’t thinking about collecting evidence.

I ask myself, too— am I overreacting? Am I?

One look in the mirror (OK, phone camera) tells me I’m not. My eyes are so puffy they look like they’ve retreated into my face. The bags under my eyes are a potent eggplant color. My shirt is damp with sweat. I can’t bring myself to smile.

Any movement outside my window makes me jump. I think the man’s gone now— nearly 6 AM— and there are more voices now, cars purring, birds singing. Human activity, oblivious to the human drama that took place in this 60 square foot room last night.

***

I am out of the room by 8 AM. I would have left sooner— I wasn’t sleeping, I haven’t slept— but I wanted to make sure there was a critical mass of people. I get dressed in the shadows and feel like I’m being watched. I put my rucksack on my back, my backpack on my front, and I look at myself in the mirror. A few positive mantras, a little self-validation. I got this. I throw the curtains of my room open.

There are a few people around, no one I recognize. I head straight to the reception, resolved to raise hell. There’s no one there. A mattress on the floor, the bed unmade. I decide not to linger and walk as fast as I can toward the tourist area of the city. For all I know, the man is in the courtyard, watching me bolt.

It is early, still, and the city doesn’t wake til mid-morning. A few early risers are opening tea stalls and pashmina shops. Auto rickshaws drive by, slowing down to ask if I want to go anywhere. I am shaking. I walk faster, look straight ahead, make no eye contact. Someone hails, “Sweetie!” the sort of catcall that’s usually just infuriating but quickly shrugged off. Today, I snap. Some sort of guttural scream comes out of me, and I’m so surprised I cover my mouth. The man smiles.

“Why are you mad? Sweetie, sweetie, why are you mad?”

***

Over three cups of black coffee and watermelon wedges, I message my sister. I ask questions that I know the answers to— questions that I should know better than to ask. Still, I go through the checklist of things I might have done wrong, of all the precautions I take and where I might have erred: I am dressed conservatively. I am not wearing makeup. I am not staying out late. I am not engaging with men— I am not even making eye contact with them.

None of those behaviors would excuse stalking and harassment. I know that, I know rationally that this is not my fault. But this keeps on happening, in India and elsewhere, and some small, guilty, searching part of me wants to know what karmic wrongdoing I am atoning for. I wish I could brush off these thoughts, but they cling on.

***

In the rickshaw on the way to the police station, I tell myself I am going as an anthropologist: interested in the process, but with little faith in the system. The rickshaw drops me off in front the police complex, and I promptly step into a puddle. I walk into a building labeled “complaints room,” squirting water all over the floor. A young woman in an orange kurta points me to a couch, low to the ground. I am sitting in front of a trim, well-groomed police offer in a beige uniform. His dark hair gleams in the artificial light. He is on the phone, but smiles at me as I sit, and I instantly warm to him. Behind his desk, a row of identical faded posters read “no cannabis.” The office is lined with earth-toned binders, bloated and discolored in places by moisture.

When the officer turns to me, I read his name on his badge but have since forgotten it— something like Prem, I think, which I liked too. I ask him if he speaks English, to which he gives a non-committal nod. I am not offered any privacy in disclosing my complaint, but I don’t ask for it either. I launch into the story, trying hard to keep the emotion out of my voice.

A man in plain clothes, who I later learned was an officer as well, shakes his head as I finish.

“Very bad manners, that boy,” he says. I’m not sure whether this trivialization of the problem is due to a difference in language or in his notion of the gravity of the situation, so I correct him.

“Well… it’s not about his manners. It’s about harassment.”

“Very, very bad manners,” he says solemnly.

Frustrated, I turn to Prem who wiggles his head and asks me to wait for his superior, who will arrive in thirty to forty minutes. In the meantime, why don’t I sit and relax. Hang out with policemen! he says, laughing, and we’ll catch the guy. I am dubious, because I’ve never even seen his face, but Prem is unfazed.

“We are police. We will find him.”

In the time that I am given to hang out with policemen (who are all, in fact, men), I make a number of observations potentially befitting an anthropologist:

The couch’s height relative to the officers’ desks makes those sitting there—presumably, those levying complaints— feel very, very small.

There is an absolutely massive lizard outside.

Everyone seems immune to the flies in the office and lets them crawl all over their uniforms unmolested, while I have no such tolerance and am swatting my arms everywhere, to the amusement of the woman in orange.

Prem has a very angular face, high cheekbones, high forehead, square jaw, pointy nose and regular— but gray— teeth. His phone rings constantly and he seems to be the officer in charge in the complaints room, as everyone else defers to him and asks for his advice.

I notice my arms are crossed over my chest and my knees are clamped together. It’s probably not abnormal for me to feel defensive, but I realize that I am particularly wary of the police. I am skeptical of the Indian government and its subsidiaries, and I came prepared to be ignored, patronized, or laughed out of the office. I have handled enough evidence to know that sexual harassment and other crimes of that caliber are hardly attended to in India, particularly in rural areas. Instead, everyone is polite, attentive, practically falling over themselves to help. Discreetly jotting down notes, I ask Prem about this.

“How many cases like this do you have every day?”

“Many, many cases. Twenty, thirty every day.”

“All in Manali?”

“Yes, but yours is especially bad.”

“Especially bad? Why?”

“Because you are a guest in our country.”

Suddenly, I understand that the inconsequence of sexual harassment is overruled by another narrative: that of the brown man harassing the white woman. Even in a country where my skin color is in the minority, I am reminded of the undue privilege of being white. I hold passports from two of the most powerful nations in the world, and these procure me the highest level of care— higher, even, than what the Indian government provides its own citizens. I feel horribly guilty, then, for acceding to this privilege. I suspect that if I really pushed this, if I filed what is called a “First Information Report”, or FIR, (which, incidentally, the police routinely denies to women making charges of rape, sex trafficking or child prostitution), this case could reach the news— not because of any groundbreaking features, not because it’s worthy of national attention, but because of my standing in the world’s pecking order.

I am not complaining about the way I am being treated. I don’t blame the actions of my harasser on anything more than a failure of personal character (or maybe of education). I believe that this sort of treatment from the police is my right, and that it should be extended to all. I also don’t have any familiarity with the Himachal Pradesh police, and it’s possible that its officers’ behavior consistently surpasses that of the U.P. police. It’s hard to say, but I do know that my personal experience is at odds with what I expected.

Things happen fast. Altogether, I am not at the station for more than three hours. Prem’s supervisor makes a call to Pine View Hotel, and Lucky-ji is called into the police station. Prem interrogates us kindly, side-by-side, but after a cursory head nod, I try not to look at Lucky-ji. Our stories corroborate each other; he claims he was home with his family at 11PM, and that some of his boys were in charge last night. He calls them in.

I tell Prem I do not want to see them, to meet them. I do not want to know what the man looks like. I worry I will latch onto his image, create a more tangible memory, etch his face into my brain.

Prem understands. He asks me if I feel safe now, with him. I say yes.

He asks what I want to do about this situation, about the man. I ask him what my options are, and he discourages legal pursuit (filing an FIR)— I am leaving the same day, and it would be a long, complicated process. I believe him; I am also anxious to avoid media attention. I ask instead if there is a strike system in place, a file that can be created that ensures the man will be charged in the event of repeated offenses. Prem brightens, and enthusiastically, says:

“Yes, if he does this again, I will arrest him!”

“But what if the man moves away, or if the case is referred to someone else? Can you keep a record of my complaint?”

“Yes, we are police, we can do anything.”

“Is there a system in place for this?”

I push harder, describing exactly what I want: the certainty that if this offense is repeated, the man will face criminal charges. Prem nods and repeats that the police can do anything, but offers no specific solution.

I am summoned to a room that is empty save for a desk, a chair and another low couch. The walls are bare except for a large calendar in Devanagari, still dated from June. Prem’s supervisor sits at the desk and motions for me to sit on the couch.

Then, three men are brought in.

I turn away before I can see their faces. They are tall, all of them.

Prem misled me. He feigned understanding me. My breath catches in my throat.

In the next room, there is someone yelling, spitting on the ground. Do I have to call the embassy? I hear whacking sounds, whimpering.

I am staring decisively at the wall, deciphering the Devanagari script on the calendar. Monday, Tuesday. The supervisor speaks loudly, sharply. In Hindi, he asks each of the boys to write, “I love you,” so he can compare their handwritings to the note I handed in. This doesn’t seem very scientific. Wednesday, Thursday. It occurs to me I haven’t told anyone I can speak and understand Hindi. I wish I couldn’t understand it now.

The boys snivel a litany of excuses, of alibis. I feel sick. I don’t want to be here, and I realize that innocent people are implicated in this case now. I start crying, sobbing, facing the wall, trying to hide my face from them. Prem’s superior asks me if I want to carry out any legal action. To the wall, I say no.

Prem asks me if I feel safe again. I don’t answer.

I can’t look. I am not the only one crying in the room. The boys are kneeling, cowering. I hear them moaning. I hear kicking, thrashing sounds. One of the boys is sprawled on the ground. Out of the corner of my eye, I can see he is tugging his ears, the way Indian children do when they feel guilty.

This doesn’t feel like the justice I wanted.

I am convulsing. I can’t breathe. The beating seems to last forever.

Prem’s supervisor asks me if I am satisfied.

“Yes,” I manage to choke out, though I’ve never meant anything less.

“Are you satisfied?” he asks again. Prem is still kicking the boy.

In a breath I say, “yes, yes I am satisfied.” In a breath, I condone this.

I am ushered out of the room, and I cover my face in my hands.

Outside, I double over trying to catch my breath. The woman in the orange kurta takes me by the elbow, sits me down in the complaint room again. She offers me water. I am still hysterical, working on my breathing.

“Stop weeping”, she says, “don’t weep.”

A few minutes later, Prem and his supervisor emerge from the other room. The supervisor, beaming, hands me my passport.

“They feel very guilty now,” he says, all smiles.

I look Prem in the eyes and ask, haltingly, just to make sure, just to confirm what I couldn’t bring myself to see—

“Did you hit them?”

“I don’t understand the question.”

I try again, slowly, deliberately.

“Did you hit them?”

Prem grins broadly.

I am excused. I hear myself thanking them. I walk out of the police station, tears streaking down my face. No one bothers me now as I make my way down the street to the rickshaw stand.

I didn’t want to see my harasser because I worried I would obsess over his face, that it would haunt me, that I would see too much that is human in him. Never knowing makes it so much easier to forget.

Instead, what is going to stay with me is Prem’s happy, gray-toothed smile.

Leave a Reply