Last November, I walked past the Imperial Theater on Broadway and spotted a gray marquee, with Lea Michele leering down at me. The neon pink text above her read “CHESS.” The musical Chess, with music by the songwriters of ABBA and lyrics by Tim Rice, is infamous for its ever-changing book, with dozens of script variations since the concept album’s release in 1984. Danny Strong has written the latest script, the first one on Broadway since 1988. How does it fare? I entered the theater to see and found myself entertained, amazed, and very confused.

This revival introduces its narrator (a snarky Bryce Pinkham) first: the Arbiter. He tells us that this is the “first, and depending on how this show goes, last, cold war musical. It’s about a chess match.” He then sets the scene and its players. Enter reigning chess champion Anatoly (a Tony-deserving Nick Christopher): deadpan, depressed, and Russian. His opponent, played by a nearly too sympathetic Aaron Tveit, is Freddie: assholish, American, and surprisingly vulnerable.

Florence—headstrong, Hungarian, and with a dark past—is Freddie’s girlfriend and second, at least at the start. Lea Michele is certainly giving her all, and if you close your eyes, she sure as hell can sing. Open them, though, and you’ll see her smile-belting through sad moments and having little chemistry with the two men she’s supposed to be in love with. Florence is ostensibly the heart of the show. Caught between the two men and the East and West (just like her country), she has the best songs and the most dynamic character. When compared to her two co-stars, however (not to mention the scene-stealing Hannah Cruz as Anatoly’s estranged wife, who enters halfway through the show), it’s clear she’s out of her depth. Still, Lea Michele is the least of the show’s problems.

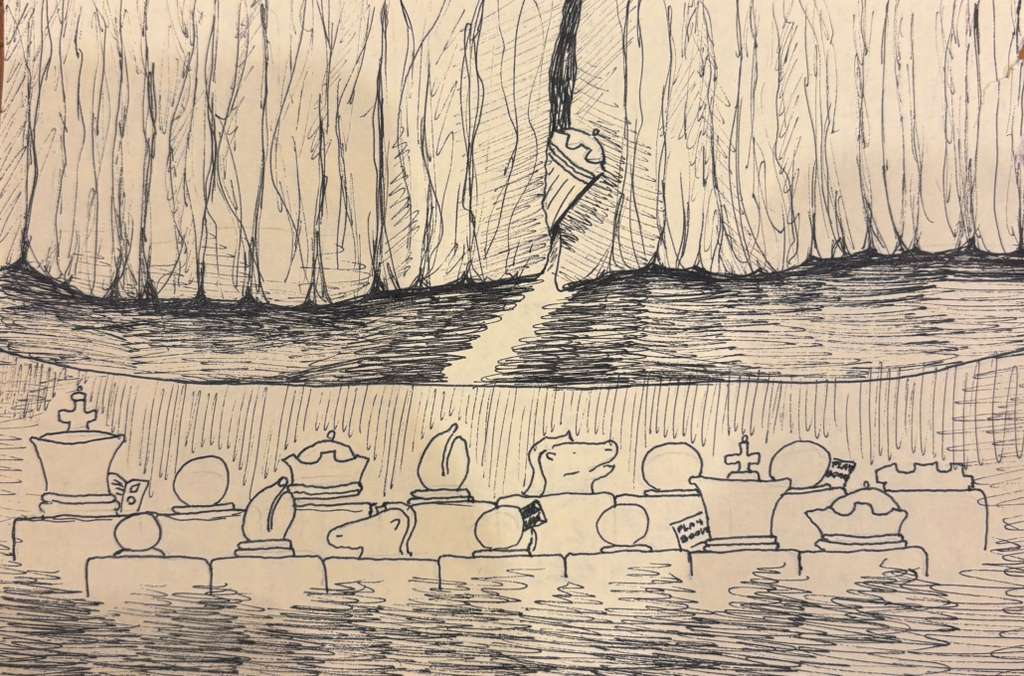

For a play ostensibly about chess, there is very little of it in Chess. Other than a white king that one of the players fidgets with on occasion, no physical chess pieces appear. The chess matches that the show usually centers around are blandly staged as players standing still and talking into microphones across from each other, saying their chess moves out loud. “Pawn to c5.” “Knight to g5.” Even the players don’t focus on the game, digressing into a monologue or a song as they think about how awful their lives are. “I hate my life. I hate myself. I’m not even human.” This is groanworthy, and the start of the mediocre writing.

The characters’ (usually ambiguous) mental illnesses have been magnified and labeled in Danny Strong’s Chess. Paranoid Freddie has now been given a diagnosis: bipolar disorder. In his first scene (which veers dangerously close to ableism in my opinion), he lies catatonic. Florence shakes him, desperately. “Your meds, Freddie! What did we talk about? You have to take your meds!” He takes them, and after a “ding!” effect, is completely back to normal. Subtlety is not Danny Strong’s strength.

Nowhere is this clearer than the final ramp-up to the climax. Normally, Chess is a microcosm of the Cold War. Loosely based on the 1972 Fischer-Spassky “Match of the Century,” it shows how building political tensions cause interpersonal ones, the effects of lives ruined by this conflict. And it still applies today. When Florence is threatened to be deported as part of manipulation by a CIA agent, you could hear a pin drop in the theater. It was a sobering reminder of the real people affected by politics, both then and now. It justifies this decades-old story being told today, and done subtly and in the right hands, it could be beautiful. This is neither of those things.

In the Chess revival, however, the fate of the world rests on this Chess match. That’s no metaphor—if things don’t go according to plan, the USSR will launch Nuclear Bombs and end the world. The stakes are ridiculously high and made me care little about anything I was watching, thinking, “What is all this petty drama? A bomb is about to be launched!” When the Arbiter tearily comes out at the end of the show and delivers a monologue saying that the acts of these chess players caused the Cold War to end, it’s clear that the show has lost any sense of reality.

I myself was ecstatic to see Chess live. In August 2024, I first listened to the 2008 Chess in Concert recording (featuring Josh Groban and Idina Menzel) and never looked back. I’ve probably listened to it hundreds of times since. There’s no one true Chess. There’s the 1984 concept album, and there’s the 2008 recording. There’s Long Beach Chess, Sydney Chess, and Swedish Chess, all with their own quirks. There’s the U.S. tour, which is different from U.S. Chess. There’s even Space Chess. And then there’s the revival, somewhere in the middle. It’s not the worst, but it’s certainly not the best. It may be the version that annoys me most, unfortunately.

Chess is a revival that is embarrassed to be itself. It takes place in the late 70s and 80s. It was written in the late 70s and 80s. Yet, the Arbiter makes jokes about RFK Jr.’s Brain Worm, and Biden’s misguided attempt to run for reelection. Introducing one of our protagonists, the cocky American Freddie Trumper, he winkingly makes a Trump allusion. He even twerks during one of his songs. I was groaning in my seat. In this Chess, I didn’t feel trusted as a viewer to care about the plot or even understand it. Everything is over-explained by narrators, and Danny Strong’s motto seems to be “tell, don’t show.” I left the theater thinking, “So that was Chess?”

There’s a vindication to it. I think Chess is a wonderful musical because it’s constantly redone. It’s a self-fulfilling prophecy in the best way. Another mediocre Chess means another chance for Chess to do what Chess does best: be born again. It still hurts, though. To wait years for something and have it not be what you hoped. To see it done by people who you feel don’t know the show like you do, don’t care about it like you. Every Chess fan probably feels the same way. Hell, maybe I’ll pain Danny Strong one day with my own adaptation.

Chess on Broadway is, admittedly, a pretty good time. If you want to see pretty lights and hear beautiful voices, go see it! And this Chess, perhaps more than any other, is firmly grounded in the modern day, for better or worse. Look how awful the world got, it seems to be saying. Could that happen again? It’s an important, if unsubtle, message for the modern day, and it works sometimes, if you can find it between the flashy choreography and corny jokes. I’m glad I went to see Chess, but I probably wouldn’t again. Whenever the next version is written, though, you will find me in the front row, eager to see whatever this show will become next.

Nora Glass is looking for a Chess partner (interested parties should contact thenassauweekly@gmail.com).